The Closer

When Fortune 500 companies are facing a massive wave of complex products liability or toxic torts cases, they call on Sheila Birnbaum ’65—master defense strategist, former law professor, and the Justice Department’s new special master of the September 11th Victim Compensation Fund.

Printer Friendly VersionBeginning in late 2002, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals was hit with a torrent of lawsuits brought by women who alleged that its two controversial hormone-replacement-therapy drugs Prempro and Premarin had caused them to develop breast cancer. Although scientific studies suggest a higher risk of breast cancer from hormone therapies, they are not conclusive, especially when it comes to particular drugs. Nonetheless, plaintiffs who had taken their cases to trial were winning staggering jury awards, including compensatory and punitive damages totaling more than $134 million to three plaintiffs in Nevada state court in 2007 (a judge reduced the total award to $58 million in 2008), and $75 million in punitive damages to a single plaintiff in a Pennsylvania court in fall 2009 (later reduced to $5.6 million).

Despite these liabilities Wyeth was in the midst of being acquired by Pfizer. So by late 2009, when the $68 billion deal had closed, Pfizer had inherited a full-blown litigation nightmare: Plaintiffs had racked up a 10-to-three record of trial wins and were clearly on a roll. With 10,000 cases still to be litigated, Pfizer, the world’s largest pharmaceutical company, had to take decisive action. The company brought in a new team that included its longtime outside counsel, Sheila Birnbaum ’65, a top products liability defense specialist who is partner and co-head of the Mass Torts and Insurance Litigation Group at New York-based Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom.

Setting her sights on defense strategy, the five-foot-two-inch Birnbaum did what she typically does in the high-stakes, bet-the-company cases she handles: She shrewdly surveyed the scope of the litigation, then proceeded to devise a game plan for stepping up settlement talks while also challenging the plaintiffs’ scientific evidence to strengthen Pfizer’s hand at trial.

By fall 2010, Pfizer had secured three straight trial wins, with juries in Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Arkansas finding that plaintiffs had failed to prove either that Prempro or Premarin had caused their breast cancer or that they had received inadequate warning of the drugs’ risks. What’s more, the federal judge overseeing multidistrict litigation proceedings in Arkansas recently barred the testimony of a few of plaintiffs’ key scientific witnesses who claimed these types of hormone-replacement therapies can cause cancer, deeming their testimonies insufficiently reliable or relevant. As a result, dozens of cases were dismissed or settled. All told, as of July Pfizer has managed to either knock out or settle some 3,300 suits, roughly a third of its caseload.

The litigation is still far from over. Yet thanks to Birnbaum’s efforts, said Pfizer in-house attorney Malini Moorthy last May, the momentum, at least for now, is no longer so heavily on the plaintiffs’ side. “I don’t want to tempt fate, but it’s fair to say the pendulum has swung,” says Moorthy. “We’ve evened up the game.”

Impressive as this turnabout has been, it is what clients expect from the 71-year-old Birnbaum, who has spent much of her career helping corporate defendants resolve their most difficult and costly litigation problems. Take Dow Corning’s leaky silicone gel breast implants, W.R. Grace’s asbestos contamination, or State Farm’s litigation involving claims arising from Hurricane Katrina. Birnbaum has played an integral role in defending and settling them all, not to mention countless other major mass torts cases involving everything from salmonella contamination to toxic spills to alleged injuries from cell phones.

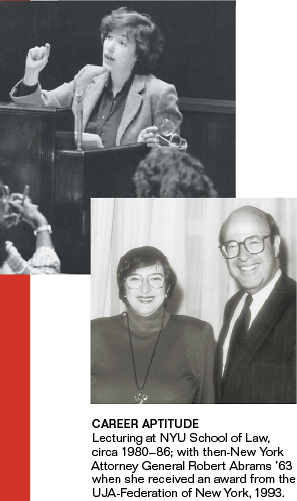

Most recently, Birnbaum was tapped by U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder to serve as the special master of the revived September 11th Victim Compensation Fund. She is charged with distributing $2.8 billion to compensate Ground Zero rescue workers and New York residents who have suffered debilitating health problems in the aftermath of the World Trade Center attacks. This exceedingly difficult and public role complements the one she held between 2006 and 2009, when she successfully mediated settlements totaling $500 million for 92 of the 95 victims’ families who chose to litigate their claims instead of accepting compensation through the original 9/11 fund, administered by Kenneth Feinberg ’70.

Knowing how and when to settle headline-making cases like these have elevated Birnbaum to the pinnacle of the legal profession. She has been called a “legal genius,” a “lawyer’s lawyer,” and the undisputed “Queen of Torts.” She routinely comes in near the top (if not at the top) of the products liability defense bar in lawyer rankings by Chambers, Who’s Who, and other legal industry publications. And when the National Law Journal assembles its picks for the 100 most influential lawyers in the country, or when Fortune and Crain’s New York Business choose the most powerful national and local women business leaders, Birnbaum’s name is invariably on the list.

“On every type of serious matter, Sheila is my secret weapon,” says Eve Burton, general counsel of Hearst Corporation, a longtime client of Birnbaum’s. Even Zoe Littlepage, a lead plaintiffs’ attorney in the Prempro and Premarin litigation, says she can’t help but admire Birnbaum’s prowess as a tactician and the artful way she plots and maneuvers to advance her clients’ goals. So much so that at their first meeting Littlepage immediately went up to shake Birnbaum’s hand. “She’s a legend,” says Littlepage. “I told her, ‘I finally got to meet the master puppeteer.’”

Indeed, over more than four decades, as both a law professor and practicing attorney, Birnbaum has not only set standards and practices that helped to pioneer the practices of products liability and mass torts law. She has also blazed a path for women in the profession as a top rainmaker and longtime leader at Skadden, one of the world’s biggest law firms, with 2,000 lawyers around the globe and $2 billion–plus in annual revenue. She has even argued and won two Supreme Court cases, including State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Co. v. Campbell et al., a landmark 2003 defense victory in the long-running battle over punitive damages. “Pretty good for a torts lawyer,” quips Birnbaum.

Visiting Birnbaum’s office at Skadden’s 4 Times Square headquarters, one sees the usual signs of a successful senior partner and rainmaker. There is the 42nd-floor view of downtown Manhattan, including a dramatic close-up of the Empire State Building’s upper reaches. Papers and overstuffed file folders are piled on nearly every horizontal surface. On the coffee table is the odd tennis trophy amid a small village of gleaming crystal recognition and appreciation awards. Hanging on the walls, stacked on the floor, and propped up on a credenza are dozens of framed Wall Street Journal, New York Times, and legal journal newspaper articles, plus plaques and awards from women’s groups, Jewish groups, schools, and professional organizations. She has a mounted Louisville Slugger on a windowsill—a souvenir from a conference in Kentucky—along with a delightfully odd alligator sculpture with the words “Lady Litigator” painted on it. Here and there are photos, including a snapshot of Birnbaum with a beaming Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor.

Most days Birnbaum gets to this office before 8:00 a.m. and works until 7:00 p.m., then logs additional hours during nights and weekends from her homes on Manhattan’s East Side and in East Hampton. She also maintains a sometimes grueling travel schedule: In one recent monthlong stretch, Birnbaum hopscotched between London (for a critical arbitration), Philadelphia (for oral arguments in a key appeal), and Little Rock (for a crucial hearing in the Prempro multidistrict litigation proceedings) before returning to Skadden’s Manhattan offices, packing in three full days, then jumping on a plane to Phoenix, where she helped lead a Sedona Conference panel discussion on mass torts and punitive damages.

Despite her devotion to her job and her climb to the top of megafirm Skadden, Birnbaum defies the stereotype most people have of the diehard corporate lawyer. For one, although she fights to restrain punitive damages—which aligns her with Republican reform efforts—she is a reliable Democratic voter. And although she is a fierce defender of her clients, she has also earned the respect and affection of members of the plaintiffs’ bar, among them Christopher Seeger, co-founder of Seeger Weiss, who considers Birnbaum a mentor and has sought her advice on cases in which her clients were not involved. She is known as a consensus-builder as well as an excellent listener who is generous with her time and advice for younger attorneys. “She’s old-school in the way she relishes her role as a lawyer and a teacher,” says Skadden products liability partner Mark Cheffo, who adds that Birnbaum often urges him and other veteran lawyers to bring junior associates along to key depositions and hearings.

Friends and colleagues add that there’s nothing affected, showy, or self-important about her. “With Sheila, there’s no pretense and no big ego to be assuaged,” says Matthew Mallow ’67 (LL.M. ’68), a former Skadden partner and longtime friend. Indeed, although she can certainly afford to be extravagant, Birnbaum still balks at paying exorbitant prices for first-class air travel, using her frequent-flier miles to upgrade instead. This frugality harks back to Birnbaum’s childhood in a lower-middle-class section of the Bronx. Even her voice, surprisingly sweet, almost girlish, has an accent that still hints of her old neighborhood. “Like they say, you can take the girl out of the Bronx, but you can never take the Bronx out of the girl,” says Barbara Wrubel, a recently retired Skadden partner who is one of Birnbaum’s closest friends. “She really is still Sheila from the Bronx.”

The eldest of three children, Birnbaum, who was born Sheila Lubetsky, grew up in the mainly working-class, southeast section of the borough, the kind of old-style New York neighborhood where mothers yelled out apartment windows and kids spent summer days playing stickball in the streets. Birnbaum could be counted on to join in. “I was a tomboy,” she says. “I didn’t like dolls.”

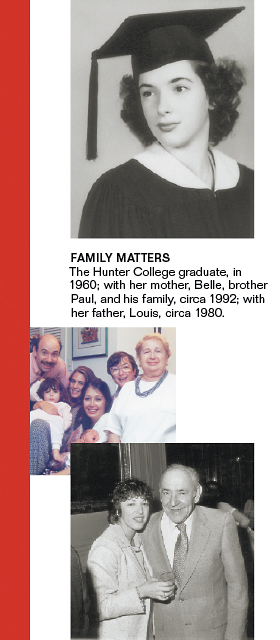

Her parents, Belle and Louis Lubetsky, didn’t make much money from the small grocery store they ran in Harlem. And space in the two-bedroom apartment that Birnbaum’s family shared with her grandmother (and sometimes an aunt) was definitely tight. But Birnbaum says she never really wanted for anything and recalls a safe, carefree childhood.

Though neither of her parents had gone to college, and her Russian immigrant father hadn’t finished high school, they were big believers in the American Dream and were determined that their children would get a better education than they had. Birnbaum was a standout student at P.S. 50, and though she says she wasn’t at “the top of the top” of her classes, she apparently made a strong enough impression that when her brother Paul, who’s 10 years her junior, came along, teachers would still gush over Sheila. “They’d all say, ‘Oh, you’re Sheila Lubetsky’s brother,’” says Paul. “I’ve been following in her footsteps all my life.”

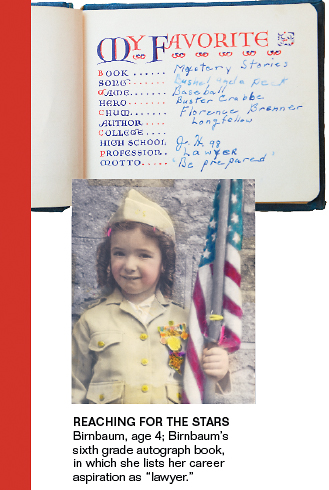

Birnbaum isn’t sure where she first got the notion that she’d like to be a lawyer. Growing up, she says her family didn’t know any attorneys, much less any women attorneys, nor does she remember reading books or seeing television shows or movies about lawyers. Yet somehow when she filled in the space for My Favorite Profession in her sixth-grade autograph book, she wrote down “lawyer.” The only explanation that Birnbaum can think of is that she might have been inspired by one of the current events discussions that a favorite teacher, Mrs. Stahl, used to lead.

There were some other early signs that she might be cut out for courtroom combat, however. Her brother Paul recounts the time when a neighborhood bully started harassing her. Birnbaum’s mother, who caught the action from the window of the family’s apartment, urged her to fight back. Birnbaum, 11 or 12 at the time, did just that. “She turned around and walloped him,” says Paul. “He never bothered our family again.”

Birnbaum majored in history with a minor in political science at Hunter College. When she took a law survey course covering torts, property, and criminal law, she says the subject instantly clicked with her and helped crystallize her elementary-school dream of being a lawyer. “It was clear to me that I wanted to go to law school,” says Birnbaum, who also participated in a mock World Court at Hunter and loved the complexity of the issues and the debating.

The problem was that women at the time weren’t supposed to go to law school or become attorneys. They were expected to get married as soon as possible, and if they had to work, being a teacher was about the only socially acceptable option. “It’s hard to imagine the pressure we were under to go into teaching,” says Birnbaum, who remembers feeling as if her only choice was to go with the flow.

Thus, a week before she graduated cum laude from Hunter in May 1960, she married Bernard Birnbaum, an accountant. And that fall she started a job teaching fourth grade at P.S. 62 in the South Bronx, several miles from where she grew up. “Everybody was going to teach, so that’s what you did,” says Birnbaum. “That’s what was expected.”

Birnbaum liked her students, but from the start it was clear that teaching fourth-graders just didn’t provide the kind of intellectual challenge she was looking for. She took night classes at Hunter, where she got an M.A. in history. But her dream of becoming a lawyer kept nagging. So late in 1962, she finally decided to quit her job. In the new year, she enrolled at New York University School of Law in a program that allowed her to finish in two and a half years by taking courses continuously, without summer breaks. She was one of just 13 women in her class of 360 students.

The very month after she matriculated, February 1963, the watershed book The Feminine Mystique, by Betty Friedan, helped ignite the feminist movement. For Birnbaum, the bestseller was an affirmation that she could really have the kind of career she knew she wanted. “It really crystallized the fact that you could be a woman and have a life,” recalls Birnbaum.

Though some men would certainly have been threatened by their wife making such a bold move, Birnbaum says her husband, who also was taking classes at Brooklyn Law School at night, was encouraging. Even so, Birnbaum says, the two were “growing apart.” Within two years after she started at NYU Law, they decided to divorce.

At NYU Law, Birnbaum excelled in her classes and developed a clear interest in litigation. She jumped at the chance to test her oral argument skills in moot court competition. It turned out to be a fortuitous move: Birnbaum and her team not only won handily, but the hypothetical case happened to focus on the then-nascent area of products liability law, in the wake of a landmark 1963 decision by the California Supreme Court in Greenman v. Yuba Power Products. That ruling set forth the doctrine of strict liability for defective products, thus making it far easier for purchasers of those goods to pursue damages regardless of whether the manufacturer was found to have been negligent or at fault. It was, as Birnbaum recalls, a whole new concept, and she and her team wound up spending the better part of a year debating the parameters of the new doctrine and trying to understand how strict liability worked.

“She was always asking questions,” says moot court teammate Gorman Reilly ’65, who also remembers her as being very organized and having a real zest for the law. “She could look below the surface and facts. In making a court presentation, she had a way of getting to the point and getting [the judges] on the panel to go along with her arguments.” He adds, “You could just see that she was really made for this.”

After graduating, Birnbaum—with the assistance of a friend who had a talent for typing—sent out close to 100 letters to law firms around the city before landing an interview and a less-than-enthusiastic job offer from Berman & Frost, a small litigation firm on William Street that handled a mix of plaintiffs and defense-side matters. “They weren’t sure they wanted me,” says Birnbaum, who recalls that the firm had never hired a woman lawyer before and made it clear in the interview that they had strong doubts about whether she was up to the job. “I remember them asking me what I would do if one of them called from court and needed me to check on a decision right away,” recounts Birnbaum, who responded with the obvious answer: She’d simply go to the firm’s library and look it up. “I think they expected I would fall apart and cry,” she says with a laugh.

In making their offer, according to Birnbaum, the firm’s senior partners also informed her that, at least for starters, she’d be earning $1,000 a year less than a man in her position. Birnbaum took the job anyway. She quickly proved that she knew what she was doing. Within three months, she was making the same salary as her male counterparts, and over time she was given more and more responsibility on new matters. Some were simple personal-injury and slip-and-fall cases in which she represented plaintiffs. Others, however, happened to involve cutting-edge issues in the young but fast-growing area of products liability law, including a huge matter Birnbaum took on in the late 1960s for Syntex Corporation, a pharmaceutical company that was facing hundreds of lawsuits alleging that its oral contraceptives caused blood clots and strokes.

[SIDEBAR: An Interpreter of Maladies]

The sheer volume of suits was larger than almost any company had had to fend off before, and though no one at the time called it a mass tort, says Birnbaum, that’s what it was. She and other lawyers for Syntex’s co-defendants had to invent a new approach for managing such large-scale litigation, including setting up a national defense team and establishing ways to organize the massive discovery effort and ensure that defense filings across various jurisdictions were consistent. “We were sort of writing the rules,” says Birnbaum, who traveled all over the country attending meetings and hearings in connection with the Syntex litigation. “We were starting to create a blueprint for how these kinds of cases would be handled.”

As more and more states followed California’s lead and adopted the doctrine of strict liability, a new plaintiffs’ bar specializing in products liability matters emerged. And with consumer advocate Ralph Nader ratcheting up his campaign against defective car designs and other allegedly unsafe products, plaintiffs’ lawyers had a host of new targets. It was clear a tidal wave of large-scale litigation was coming.

Along with Syntex, Birnbaum also represented Chrysler Motor Corporation in connection with claims that the steering system on its Newport Custom sedan was defective, and she wound up taking a lead role in the car giant’s appeal in Codling v. Paglia, a seminal 1973 case that established the doctrine of strict products liability in New York State. Despite the court adopting strict liability, Birnbaum notes that the decision was actually slightly more pro-defendant than in other states. “It was the best a defendant could do given the way the law was shifting,” says Birnbaum.

While Birnbaum was making a name as an expert in products liability matters, the dean of Fordham University School of Law, Joseph McLaughlin, was seeking to add women to a virtually all-male faculty. In 1974, he made Birnbaum a surprise job offer, and she accepted. “Somehow he convinced me,” says Birnbaum, who recalls that McLaughlin played heavily on the fact that she’d be a pioneer, opening doors for women in the law.

Birnbaum’s detour into academia ultimately lasted a dozen years—first at Fordham, then at her alma mater NYU Law, where she taught from 1980 to 1986, and served a two-year stint as associate dean. Though it has been 25 years since Birnbaum left the NYU Law staff, she enthusiastically recalls how much she enjoyed the back-and-forth with her students. “I loved teaching” law students, says Birnbaum, who also appreciated the freedom to study and analyze the quickly evolving products liability landscape in a way that a busy practitioner never could.

“Sheila came and hit the ground running,” says Sylvia Law ’68, Elizabeth K. Dollard Professor of Law, Medicine, and Psychiatry, who has been on the NYU Law faculty since 1973. Indeed, Law recalls that Birnbaum not only won the instant admiration of students and colleagues, but also shared some helpful tips with Law and the handful of other women who were still a tiny minority on the faculty and sometimes struggled to get the full attention and respect of some of the male students. “She gave me some of

“Sheila came and hit the ground running,” says Sylvia Law ’68, Elizabeth K. Dollard Professor of Law, Medicine, and Psychiatry, who has been on the NYU Law faculty since 1973. Indeed, Law recalls that Birnbaum not only won the instant admiration of students and colleagues, but also shared some helpful tips with Law and the handful of other women who were still a tiny minority on the faculty and sometimes struggled to get the full attention and respect of some of the male students. “She gave me some of

the best advice I ever got,” says Law, who remembers Birnbaum telling her that she was probably too nice and needed to seize control by batting down obstreperous students the very first week of class. Birnbaum says her strategy for handling students with an attitude was to make a few barbed comments or jokes at their expense. “You’re smarter than they are,” she says. “You just confront them straight on.”

One NYU Law student from that era who is deeply indebted to Birnbaum is Gregory Miao (LL.M. ’85). He was born and raised in Shanghai and was the first Chinese-trained lawyer to come to the Law School as a visiting scholar in the thaw that followed the end of China’s Cultural Revolution.

Landing in New York in fall 1983, Miao had virtually no money and no real sense of purpose or belonging at NYU Law, because as a visiting scholar he was simply auditing classes and wasn’t really connecting with students. He could have easily spent the entire year at Washington Square drifting about. Miao recalls that Birnbaum took the time to talk to him and find out how he was doing. She strongly encouraged him to improve his English, then apply for a slot in NYU’s LL.M. program. Even better, according to Miao, she also made it her mission to help him secure the funds he needed to pay for the program once he was in. “You can’t believe how wonderful that was,” says Miao, who vividly remembers the day Birnbaum called him into her office and handed him a big check. Birnbaum, by then associate dean and in charge of the LL.M. and visiting scholars programs, remembers Miao as “just an outstanding person,” and says that her efforts were all in the line of duty.

Birnbaum’s willingness to—at least in Miao’s view—go out of her way to help him led him to spend another few years in New York after he earned his LL.M. working for Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison. Then, returning in the late 1980s to China, he ended up joining Skadden Arps (entirely independently of Birnbaum), where he is currently a partner splitting time in the Shanghai, Beijing, and Hong Kong offices and leads Skadden’s mergers and acquisitions and corporate practice in China. “I am so grateful to Sheila,” says Miao. “I was so surprised that a dean would spend that kind of time with me. It really changed my life.”

Today, Birnbaum is such a fixture at Skadden Arps that it’s a little hard to imagine her anywhere else. Still, as she recalls, it was really just a chance encounter at a Fordham faculty cocktail party in 1979 that brought her to the firm. Birnbaum says she had barely heard of Skadden at the time, but she got to talking to Skadden partner and Fordham adjunct professor John Feerick at the party, and he suggested she speak with one of the firm’s name partners, Joseph Flom, about setting up a part-time practice at the firm.

Skadden was in full growth mode at the time and actively looking to add new practice groups. Firm leaders believed Birnbaum’s expertise in products liability would be a smart fit. “For us, it was a no-brainer,” recalls former Skadden partner Stephen Axinn. He and other Skadden veterans, including Irene Sullivan, who would become one of the first woman partners, contend that gender was never much of an obstacle at Skadden, which has always prided itself on its entrepreneurial, egalitarian culture. “It was very much a meritocracy,” says Sullivan. “If Joe [Flom] believed you were talented, and you worked hard, that’s what mattered.”

Birnbaum says she had originally conceived of her work for Skadden as a “nice little side job.” Almost as soon as she joined the firm as counsel, however, clients with major products liability exposure began calling. Birnbaum’s practice, which included both products liability defense and insurance coverage matters, took off.

It wasn’t just the volume of new cases. The sheer size of the litigation was also increasing exponentially, with thousands upon thousands of plaintiffs now claiming injuries—a development that, as Birnbaum points out, was spurred by the rise of computers, which made it possible for the plaintiffs’ bar to instantly replicate filings. “Without computers you couldn’t have mass torts or class actions,” says Birnbaum. “There’d be just no way to do it.”

Birnbaum began hiring new lawyers to help her keep up with all the work. By the early 1980s, however, Birnbaum was spending so many long nights and weekends at Skadden that she decided it was time to leave NYU Law and join the firm as a full-time partner. In the months and years that followed, Birnbaum’s workload only got larger. In 1984, Dow Corning enlisted her help fending off what eventually mushroomed into more than 40,000 suits by women who claimed that the company’s silicone gel breast implants caused a range of serious autoimmune diseases. During the 1980s, she also defended Olin Corporation in thousands of suits involving DDT, as well as Georgia-Pacific in a mammoth class action in Louisiana alleging the company had contaminated the local water supply in 1981. Plus, she served as lead defense counsel on more than 100,000 asbestos-related lawsuits against insurance giant Metropolitan Life.

And that’s just a sampling. Indeed, as the numbers of large-scale class actions, products liability, and toxic torts cases continued to explode, Birnbaum became the go-to defense lawyer a long list of Fortune 500 companies. “Sheila was really ahead of the curve,” says Samuel Issacharoff, Bonnie and Richard Reiss Professor of Constitutional Law, an expert in complex litigation who faced Birnbaum in a water contamination case against BP, Chevron, and other oil giants involving the gasoline additive MTBE. In the early wave of products liability cases, Issacharoff notes, many companies would hire individual lawyers to litigate each matter separately. But Birnbaum understood that the flood of products liability litigation would make that strategy untenable. She built a practice around the idea of providing comprehensive representation to defendants with the aim of global resolution of their liabilities, says Issacharoff: “She anticipated where the law would require a whole different kind of representation.”

As co-head of Skadden’s Mass Torts and Insurance Litigation Group, Birnbaum oversees about 60 lawyers. She views her role as a big-picture strategist—assessing the present and future scope of the litigation, weighing the risks, and figuring out the best way to proceed to limit her clients’ exposure. “I’m always looking at what the endgame is,” says Birnbaum, who notes that it’s exceedingly rare for the defense to find a silver bullet that can suddenly make the thousands of cases in a mass torts litigation go away.

Allies and adversaries alike contend that one of her greatest talents lies in devising creative ways to resolve even the most massive, complicated matters. “A lot of defense lawyers have drunk the Kool- Aid—all they want to do is litigate,” says plaintiffs’ attorney Perry Weitz, co-founder of Weitz & Luxenberg. In the vast majority of mass torts and class actions, Birnbaum contends, the most cost-effective course of action for clients is to settle. The key question is when and for how much, she says: “You have to ask how you are going to win the most battles and skirmishes along the way so you get to the point where the litigation can be settled for the least amount of money.”

It is during those battles and skirmishes that Birnbaum demonstrates her strength and leadership. She is calm and even-tempered under pressure, even when she’s marshaling Skadden associates to meet deadlines on critical motions. “She’s our Rock of Gibraltar,” says David Zornow, global head of Skadden’s Litigation and Controversy practices. And she has a firm hand in defusing volatile situations. During settlement talks for thousands of toxic injury cases against the maker of the diet drug Dexatrim, Christopher Seeger recalls that one of his fellow plaintiffs’ attorneys jumped out of his chair and began yelling expletives in Birnbaum’s face. He says Birnbaum stuck her finger in the lawyer’s chest, said a few choice words, and put him right back into his chair. Seeger, who has had his own share of heated moments with Birnbaum over the years, contends that “if you push her too hard, the Bronx is going to come out.”

It is during those battles and skirmishes that Birnbaum demonstrates her strength and leadership. She is calm and even-tempered under pressure, even when she’s marshaling Skadden associates to meet deadlines on critical motions. “She’s our Rock of Gibraltar,” says David Zornow, global head of Skadden’s Litigation and Controversy practices. And she has a firm hand in defusing volatile situations. During settlement talks for thousands of toxic injury cases against the maker of the diet drug Dexatrim, Christopher Seeger recalls that one of his fellow plaintiffs’ attorneys jumped out of his chair and began yelling expletives in Birnbaum’s face. He says Birnbaum stuck her finger in the lawyer’s chest, said a few choice words, and put him right back into his chair. Seeger, who has had his own share of heated moments with Birnbaum over the years, contends that “if you push her too hard, the Bronx is going to come out.”

Seeger and other plaintiffs’ attorneys say, however, that Birnbaum is almost always pleasant to deal with, listening and respecting their positions. When the time comes to close settlement talks, Birnbaum is pragmatic and flexible, they say, and when she makes a promise during negotiations, she delivers. “When she gives you her word, you can count on it,” says Weitz, who has faced Birnbaum across the bargaining table in at least a dozen cases. “She’s shown she’s someone the plaintiffs’ side can trust.”

Over the years, some of Birnbaum’s pro-plaintiffs friends and colleagues on the NYU Law faculty have ribbed her about the merits of helping polluters, manufacturers of drugs, and the many other corporate defendants she represents to get off easy. “I tell her she’s a running dog for corporate America,” says University Professor Arthur Miller with a chuckle. To which, he says, Birnbaum can be counted on to retort that he’s “a supporter of extortionist” plaintiffs’ lawyers. Likewise, Sylvia Law recalls debating Birnbaum about whether helping to block plaintiffs who might have suffered real injuries from collecting damages is a worthy endeavor. “I thought that corporations should be held accountable,” says Law, while Birnbaum was sympathetic to the defendants.

Those sorts of debates haven’t done much to change the way Birnbaum regards her work. She maintains that she, too, firmly believes that corporations should not be let off the hook for willful misconduct. If, say, a drug company hid studies from the Food and Drug Administration showing a medication was harmful, then that company should be punished, says Birnbaum. The problem is that the facts on the whole in the vast majority of drug injury cases and many other types of toxic torts litigation are never that simple. She contends pieces of the story often get distorted and are used to malign corporate defendants. “It’s very easy to take an e-mail or document out of context to create passion and prejudice against a big corporation” and win a huge award, says Birnbaum. “But maybe you’re taking money from corporate shareholders and workers.”

Birnbaum says she is moved by the plight of many of the plaintiffs whose cases she defends, such as the women with advanced breast cancer in the Prempro and Premarin litigation. Still, as tragic as those women’s stories are, she insists that there’s just no proof that the two hormone-replacement drugs caused their illness. “No one knows what causes breast cancer,” says Birnbaum. “No doctor can tell a jury that the mere fact that a plaintiff took a particular drug caused their individual injuries.”

The Dow Corning case serves as a cautionary tale that helps to explain how Birnbaum can see past the swirling emotional drama of plaintiffs’ stories and insist on scientific proof of causation. Despite the tremendous hype in the 1980s and ’90s about the debilitating health issues the silicone gel breast implants allegedly caused, in the end the independent panel of scientific experts who examined the evidence found there was no credible proof linking the implants to the alleged injuries. “We knew the science [the plaintiffs were relying on] was very weak,” says Birnbaum, who helped lead the push for an independent review of the scientific evidence. “It was a decisive win for defendants.” Unfortunately for the company, by the time the review was completed Dow Corning had already declared bankruptcy and opted to settle the litigation.

And don’t even try to argue the merits of large punitive damages. While she supports the jury process, Birnbaum says large punitive damages are emotionally driven, and therefore frequently reduced by judges. She is proud of her Supreme Court win on behalf of State Farm in the 2003 Campbell case, which challenged a $145 million punitive damages verdict that State Farm had been hit with in Utah for bad faith in settling a case. Birnbaum argued that the size of the award was so excessive compared to compensatory damages that it violated State Farm’s due process rights under the 14th Amendment. She asserted that since civil defendants have fewer rights than criminal ones, grossly excessive or arbitrary punishment is unjust. A majority of the justices agreed and proceeded to lay down new guidelines on “reasonableness” for lower courts to consider when reviewing punitive damage awards. “Birnbaum argued quite forcefully that a punitive award must be limited to the rights violation suffered by the plaintiff,” says Mark Geistfeld, an expert in punitive damages who became the Sheila Lubetsky Birnbaum Professor of Civil Litigation in 2009. “Campbell has largely reoriented the hugely important tort practice of punitive damages away from the punishment of social wrongdoing to the redress of the individual issue in the tort claim.”

Birnbaum says the Court’s decision has clearly had a positive impact in making punitive damage awards more rational and predictable, in addition to reducing their size. And she contends that the net effect is actually pro-consumer. “When you punish a corporation [with a huge award], consumers often end up paying for it with higher prices,” says Birnbaum. In fact, she says, it’s simply a windfall for plaintiffs and their lawyers.

How a lawyer whose victory in Campbell was called “a big win for corporate America” by the Washington Post is not a Republican boils down to being, at heart, a hometown girl.

Growing up in the Democratic bastion of the Bronx, Birnbaum says, she never knew any Republicans. And though she officially labels herself an independent, she says that she almost invariably supports Democrats. During the 2008 presidential campaign, she was an enthusiastic donor to Hillary Clinton and went to Philadelphia on the day of the Pennsylvania primary to assist in the Clinton campaign’s get-out-the-vote effort. “I really wanted to see the first woman president,” says Birnbaum.

Over dinner with good friends, Birnbaum is always up for a lively debate about the latest political issues. “She loves to argue about politics,” says her friend Barbara Wrubel, who describes Birnbaum as liberal on social issues but a fiscal conservative.

Birnbaum, for her part, does say she’s strongly pro-choice, but she declines to get into her views on other hot-button issues for public consumption—especially in light of her recent appointment to oversee the 9/11 fund.

In her free time, Birnbaum can usually be found at her East Hampton home. Besides being an enthusiastic Scrabble player, she took up golf seven years ago. And all her corporate travel hasn’t dimmed her wanderlust or sense of adventure. She is an avid kayaker and outdoor enthusiast. This year she toured northern India and went snowshoeing in Aspen. “It’s just a beautiful thing to get out in the woods with the snow falling,” says Birnbaum.

She has also recently started cooking Italian food—thanks to Brooklyn Law School President Joan Wexler (and former NYU Law professor) and other longtime friends, who gave Birnbaum lessons with a private chef for her 71st birthday this past March. “We’re hoping she gets back into cooking,” says Wexler, who adds that in the past Birnbaum has hosted some great dinner parties, in addition to the party she throws in East Hampton every summer, when she treats a group of about 30 friends to an outdoor meal on the night of an annual town fireworks show.

She has also recently started cooking Italian food—thanks to Brooklyn Law School President Joan Wexler (and former NYU Law professor) and other longtime friends, who gave Birnbaum lessons with a private chef for her 71st birthday this past March. “We’re hoping she gets back into cooking,” says Wexler, who adds that in the past Birnbaum has hosted some great dinner parties, in addition to the party she throws in East Hampton every summer, when she treats a group of about 30 friends to an outdoor meal on the night of an annual town fireworks show.

Despite Birnbaum’s frenetic work schedule, Wexler and others say she’s exceptionally giving of her time and is the kind of friend who can be counted on whenever they’re in need. “We all know that Sheila will be there for us,” says Madeline Stoller, who says that when one of Stoller’s family members was ill, Birnbaum called her every day and offered helpful, practical advice.

Likewise, years back, when Stoller flew back to New York from Florida after her mother died, she says Birnbaum came to LaGuardia to pick her up at 11:00 p.m. “She’s the most supportive friend in every way possible,” says Stoller, who met Birnbaum when the two shared a summer home in the Hamptons roughly 40 years ago and credits Birnbaum with urging her to go to law school. Now retired, Stoller was in-house counsel at Wyeth Pharmaceuticals until 2006.

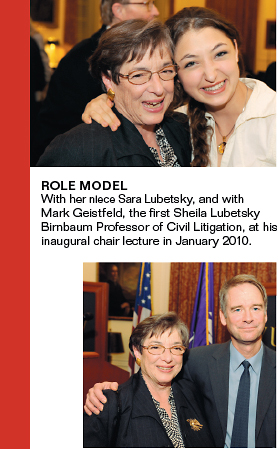

During Birnbaum’s early 40s, there was a period when she thought she might like to have children. That time came and went, but Birnbaum says she has no regrets. “I wouldn’t have been able to accomplish all I’ve accomplished,” she says, noting that she has three nieces whom she’s close to, including one—Sara, her brother Paul’s daughter—who graduated magna cum laude this spring from NYU’s College of Arts and Science.

Looking back at her many achievements, Birnbaum says she feels best about her ability to show that a woman could build a leading practice with top-tier clients and practice law at the very highest level. She’s also proud of the many things she has done to support other women lawyers, including serving as a mentor and helping to organize an annual Skadden women’s retreat, where the firm’s female partners can network with top clients. “I’ve always tried to open doors for other women,” says Birnbaum, who was also involved in the creation of the Women’s Bar Association of the State of New York.

For now, Birnbaum insists she’s still enjoying her practice at Skadden too much to think about retiring. “I love practicing law, and I intend to keep practicing as long as I can,” she says. You don’t need scientific evidence to conclude that’s a sound decision.

—

Multimedia

Multimedia