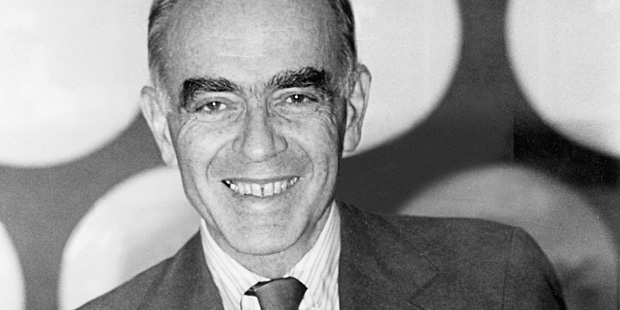

An Extraordinary Dean

Dean Emeritus Norman Redlich passed away on June 10, 2011. Below is the eulogy delivered by Dean Richard Revesz at the memorial service held on June 13.

Printer Friendly VersionNorman Redlich (LL.M. ’55) was my family’s dean. He was the dean who hired me in 1985 to join the NYU Law School faculty and during whose tenure I served for three years as a very junior faculty member. And for the last nine years, I’ve been occupying an office that I had long referred to as “Norman’s office.”

Norman was also the dean when my wife, Vicki Been ’83, was a law student. He was the dean who called her to his office to let her know in a stern but caring way that during her clerkship with Judge Edward Weinfeld, perhaps the Law School’s most illustrious alumnus at the time, she would need to uphold the Law School’s reputation and honor.

Law School Career

Norman was an extraordinary dean. Much of the Law School’s current success can be traced to Norman’s visionary leadership. Norman served in the military during World War II. Then, after graduating from Williams College in 1947 and receiving his LL.B. from Yale Law School in 1950, Norman earned his LL.M. in taxation from NYU School of Law in 1955. He joined our faculty in 1960, received tenure in 1962, and became the Judge Edward Weinfeld Professor of Law in 1983. Norman was a prolific scholar in the areas of constitutional law and professional responsibility, and authored an influential casebook in each of these areas.

Norman served as the NYU Law School dean from 1975 to 1988, and was dean emeritus at the time of his death. After stepping down as dean, he continued to teach Professional Responsibility for many years while he was counsel to the law firm of Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz.

Norman’s deanship significantly accelerated the Law School’s remarkable upward trajectory, which had begun in the early 1950s under Dean Arthur Vanderbilt. He made many transformative appointments to our faculty, including Ronald Dworkin and Thomas Nagel, whose Colloquium in Legal, Political, and Social Philosophy institutionalized the school’s commitment to interdisciplinary work; Anthony Amsterdam, who designed our Lawyering Program and greatly expanded the Law School’s clinical programs; and John Sexton, who followed in Norman’s footsteps as dean and led the Law School through 14 extraordinary years.

In addition, much of the Law School campus’s current footprint can be attributed to Norman’s vision. Both of our residence halls, D’Agostino and Mercer, were built during his deanship, and the Law Library was extended underground, making it possible for us to now connect our two main academic buildings: Vanderbilt and Furman Halls. Norman laid solid groundwork that helped propel the Law School’s success well after his deanship.

He set a high bar in another area as well. Every year, the students put together a show, called the Law Revue, pronounced Law Revuee, to distinguish it from the far more staid Law Review, the publication often seen as the hallmark of law school academic success. And at each performance Norman sang a song, written by students, which typically poked fun at him. Norman was quite self-effacing, and this kind of stage appearance must have been difficult for him, but he was an incredibly good sport.

In 1988, as Norman was getting ready to step down from the deanship, he wrote the lyrics himself. I will not sing them because this is one area in which, I’m sorry to say, the talent at the Law School’s helm has gone downhill since Norman’s time. But I will read Norman’s lyrics.

Thanks for the memories

Of listening to me croon

Each May and every June

I may not be Sinatra but I try to keep a tune

Oh, thank you so much.

Thanks, friends at NYU

Oh, how the students swore

Construction noise galore

But now we’ve Mercer, D’Agostino,

Fuchsberg still in store

Oh, thank you so much.

I tried to beef up the clinics

While other schools started as cynics

But now they are trying to mimic

Ah, now they know, I told you so.

Oh, thanks for the memories

We built a school that’s strong

And now I say so long

Just keep your sights on doing right

I know you can’t go wrong

How lovely it’s been.

Oh, thanks for the memories

The budgets were a chore

You always asked for more

I may have been a headache

I often was a bore

How lovely it’s been.

It is nice to know that his deanship was lovely to Norman. It was certainly very lovely for the Law School.

Other Accomplishments

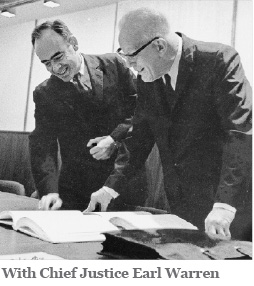

His impact on the Law School, by itself, would be considered an extraordinary accomplishment, but for Norman, it was only one facet of his remarkable career. Norman also performed significant public service in New York City and in the federal government. Just three years after joining our faculty, Norman was appointed assistant counsel to the President’s Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy (popularly known as the Warren Commission), where he investigated the relationship between Lee Harvey Oswald and Jack Ruby. He later worked in New York City’s Law Department, where, among other accomplishments, he litigated significant cases concerning the city’s pathbreaking historic preservation law. In this connection, Norman’s legal acumen and negotiating skills had already helped his friend Jane Jacobs save Washington Square Park from Robert Moses’s plans to run a highway through it. In 1972, Mayor John Lindsay named him corporation counsel, the city’s highest legal office, a position he held until he became dean of our Law School.

Norman also was devoted to improving the state of the legal profession. Among other significant leadership roles, he was chair of the American Bar Association’s Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar and a member of the ABA’s House of Delegates.

In the ABA, he was one of the leading voices for promoting and improving clinical legal education in law schools. He worked closely with Robert MacCrate and our colleagues Tony Amsterdam and Randy Hertz on the MacCrate Report, which sought to narrow the perceived gap between legal education and the legal profession. In the years following the issuance of that report, he played an important role in implementing the report’s blueprint for improving the teaching of professional skills and values in law schools.

Civil Rights and Civil Liberties

Norman was passionately committed to civil liberties and civil rights. Steven Epstein ’86, a Law School alumnus and also a Williams graduate, reported the following: “During my time at NYU Law I had some great conversations with him about Williams and his love for the place. There’s only one commercial street in Williamstown and one barber shop. He told me that when he was a student, he started a protest because the African Americans at Williams wouldn’t be served in the barber shop—and he changed that. He used it as a lesson that you can fight injustice pretty much anywhere.”

A decade later, as a young lawyer in the 1950s, Norman courageously challenged the tactics of Senator Joe McCarthy. On behalf of the National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee, he defended people blacklisted because of their refusal to answer questions before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Subsequently, then-Representative Gerald Ford sought—unsuccessfully—to have him removed from the Warren Commission as a result of these activities.

Just before joining the NYU faculty, while serving as counsel to the New York Committee to Abolish Capital Punishment, Norman brought one of the early challenges to the death penalty. Later in his career, he was on the Executive Committee of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, and chair of the National Governing Council of the American Jewish Congress. He also served as a co-chair of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law and received that organization’s highest award—the Whitney North Seymour Award—in 1993.

Conclusion

In his wonderful speech at the Law School’s graduation in 1985, Norman commented on another Law Revue (as in Law Revuee) song, titled “I Want it All.” The song had been written by the students from the perspective of a woman, as in “I want to be Scarlett O’Hara, Joan of Arc, Lauren Bacall.” For his speech, Norman wrote a companion song from the perspective of a man, which I will read:

I want to be Mario Cuomo and work

pro bono

I want to shop at Tower and be a

legal power

I want to run the Fed and play in the

Grateful Dead

I want to be seen at the ballet and at Shea

I want to be Henry K., Dr. J., I.M. Pei,

Reggie J., and Dr. K.

I want to run the firm

I want to be David Byrne

I want to be Arthur Ashe and Sam Dash

I want to be Andrew Young, Robert Young,

Coleman Young, and Neil Young

I want to be Clarence Darrow and

Robert De Niro

I want to get top fees and honorary degrees

I want to fight the crooks, be Albert Brooks

Negotiate Ewing’s deal, eat a five-star meal

Be a loving dad, a supportive mate

Have an East Side pad, be Secretary of

State

I want to be Earl Warren, and drive a car

that’s foreign

I want to win big trials, run four-minute

miles

Clean up the sludge, and be a judge

I want it all!

Those of you who knew Norman well know how close he came to having it all, even by the standard of this song. But to the Law School graduates whom he was addressing, for whom accomplishment of this magnitude might have seemed unfathomable at the time, he had the following words of wisdom: “If you maintain a good sense of balance, a bit of humor, resist the pressures to be narrowed into narrow grooves, and define what you want in terms of a personal and professional life of meaning and concern, then, indeed, you can have it all.” By this standard, there is absolutely no doubt that Norman had it all.

To conclude, Norman’s extraordinary energy and powerful leadership inspired not only generations of students and faculty, but also a much broader community of lawyers and public servants. Dean Redlich: Vicki and I, as well as so many others, will deeply miss you.

—

Multimedia

Multimedia