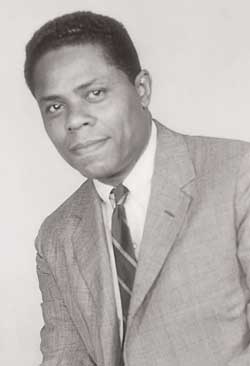

Charles Conley (1921–2010)

Trusted counsel, accomplished Alabama civil rights attorney

Printer Friendly Version A half-century ago, when audacious black southern men had grave reason to fear for their lives, Charles Swinger Conley ’55 hung a shingle in his native Montgomery, Alabama, and set about becoming a “radical threat to the status quo,” says NYU Law Professor Bryan Stevenson, founder and executive director of the Montgomery-based Equal Justice Initiative. During his long and illustrious career, Conley fought civil rights cases small and large, counseled movement leaders Martin Luther King Jr. and Ralph Abernathy, and eventually became Alabama’s first elected black judge. “It was tremendously courageous for an African- American lawyer to challenge the system that existed in the ’50s and ’60s throughout the South,” says Stevenson. “Judge Conley’s accomplishments shape and inspire us in our work today.”

A half-century ago, when audacious black southern men had grave reason to fear for their lives, Charles Swinger Conley ’55 hung a shingle in his native Montgomery, Alabama, and set about becoming a “radical threat to the status quo,” says NYU Law Professor Bryan Stevenson, founder and executive director of the Montgomery-based Equal Justice Initiative. During his long and illustrious career, Conley fought civil rights cases small and large, counseled movement leaders Martin Luther King Jr. and Ralph Abernathy, and eventually became Alabama’s first elected black judge. “It was tremendously courageous for an African- American lawyer to challenge the system that existed in the ’50s and ’60s throughout the South,” says Stevenson. “Judge Conley’s accomplishments shape and inspire us in our work today.”

Conley died last September at age 89. Before his death, he had made provisions for a $1.2 million gift to his alma mater that will endow the Honorable Charles Swinger Conley Scholarship Fund and will also fund a permanent memorial at the Law School honoring Conley’s outstanding legal accomplishments and historic career.

Conley’s law office on Bainbridge Street—walking distance from King’s Dexter Avenue Baptist Church—was informally known as Executive House. During the 1960s, it was a center of social activism in a city that was itself ground zero for the civil rights movement. Conley’s strategic counsel was sought by the likes of Rosa Parks, leader of the Montgomery bus boycott; King, Abernathy, and other members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference; and fellow crusading lawyers Virginia Foster Durr and Fred Gray.

Upstairs at Executive House, Conley maintained overnight accommodations—full bar included—for out-of-town activists and visiting counsel such as New Yorkers William Kunstler and Arthur Kinoy.

Conley was engaged in a full-scale battle for civil rights. In Cobb v. Montgomery Library Board (1962), for example, Conley’s pro bono client was a black child denied use of the city’s main library. When Conley prevailed and the U.S. District Court in Montgomery ordered the library desegregated, officials removed all the visitor chairs from the library. No patron, black or white, could sit. “Well, that was just pure spite,” says Conley’s widow, Ellen, “but it didn’t last long.” In one of Conley’s most significant victories, Seals v. Wiman, also in 1962, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in New Orleans overturned the conviction of Conley’s client, Willie Seals, a young black man found guilty of raping a white woman in 1958 by an allwhite jury and sentenced to Alabama’s death row. The court held that exclusion of blacks from Alabama’s jury rolls violated the 14th Amendment.

Conley also played a part in the landmark 1964 Supreme Court case New York Times Co. v. Sullivan. He represented four ministers, including Abernathy, as coplaintiffs with the Times, contributing to briefs in a case that ultimately established an “actual malice” standard had to be met before news accounts about public officials could be deemed libelous. The ruling allowed unfettered coverage of civil rights demonstrations then taking place throughout the South.

Ellen Conley was her husband’s chauffeur and protector in the turbulent ’60s, especially when he worked at his office late into the night. “I’d always insist on getting out of the car first,” she said in a telephone interview. “If a bullet was coming, it would get me. Chuck had important work to finish.”

—

Multimedia

Multimedia