Partner for Life

For the lion’s share of 60 years,

NYU Chair Martin Lipton ’55 has

served as a trusted adviser to four NYU

presidents and six Law School deans.

For the lion’s share of 60 years, NYU Chair Martin Lipton ’55 has served as a trusted adviser to four NYU presidents and six Law School deans.

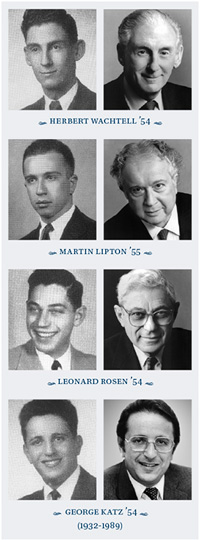

Printer Friendly VersionNot long after he graduated from New York University School of Law, Martin Lipton ’55 returned to campus for a reception, where he ran into Dean Russell Niles. Dean Niles was Lipton’s former mentor, and he’d been keeping tabs on his protégé. In the few years since graduation, Lipton had gone on to a fellowship at Columbia Law School, where he studied under Adolf Berle, co-author of the landmark book on corporate law, The Modern Corporation and Private Property, and then to a clerkship with Judge Edward Weinfeld ’21 of the US District Court for the Southern District of New York. At the moment, Lipton was working at Seligson, Morris & Neuberger, a small firm that advised big companies such as Pepsi. There, he worked with fellow NYU alums George Katz ’54 and Leonard Rosen ’54. Lipton, Rosen, and Katz had been referring litigation to a fourth NYU graduate, Herbert Wachtell ’54.

At the reception, Dean Niles asked Lipton what he was working on. Lipton said he was preparing an SEC registration statement for a client. Niles mentioned that there was an opening on the NYU faculty; Chester Lane, former general counsel of the SEC and an adjunct professor at NYU who taught securities regulation, had passed away. Niles needed an interim professor. He offered Lane’s old class notes to Lipton, along with the job, and said: “Don’t worry, Marty. By next week I’ll have someone who knows how.”

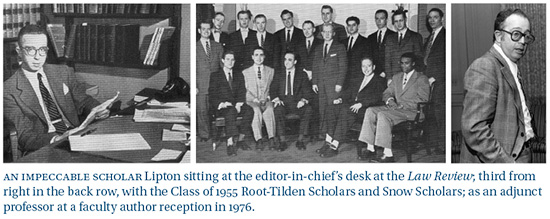

Next week came and went. Niles never found a replacement. Lipton would spend the better part of the 1960s and 1970s teaching securities regulation and corporate law part-time. Later, he would continue his association with NYU by serving as chairman of the Law School board and then of the University board, a post he holds today, more than 60 years after arriving on campus from the University of Pennsylvania. Law school students and fellow attorneys might know Lipton for his creation of the “poison pill,” an important innovation in corporate law that’s used to defend against takeovers. Less well known, however, is Lipton’s lifelong association with NYU, where alumni and administrators credit him with raising crucial funds and captaining NYU’s ascent from a small commuter school for working-class students into a premier global university.

The rise of NYU and the School of Law over the past half-century is particularly impressive when considering how static the world of higher education tends to be. In the constellation of great centers of learning, the stars move mostly in imperceptible ways. There have been a handful of exceptions, such as the trajectory of Stanford in the second half of the 20th century, although that was fueled heavily by money from Hewlett-Packard. NYU has a smaller endowment than its peer schools. Over the past 40 years as a trustee of both the University and Law School boards, Lipton has helped NYU leverage its non-financial assets, such as its location in the heart of New York City, as well as the loyalty of its alumni, typified by people like Evan Chesler ’75, chairman of Cravath, Swaine & Moore, and Stern alumnus Kenneth Langone, a founder of the Home Depot. But nowhere is that loyalty more evident than at Lipton’s own firm. Two of his partners, Herbert Wachtell and Eric Roth ’77, serve on the Law School board. Partner David Katz ’88 has taught a Law School course on M&A for the past 20 years, while another partner, Lawrence Pedowitz ’72, co-chairs the board of NYU’s Brennan Center for Justice.

“The Law School has had an established trajectory over the past 60 years,” says Richard Revesz, who ended 11 years as dean this May, “and I see it as connected to the emergence of Marty and his firm as major players. Wachtell Lipton is very much an NYU story.”

“The Law School has had an established trajectory over the past 60 years,” says Richard Revesz, who ended 11 years as dean this May, “and I see it as connected to the emergence of Marty and his firm as major players. Wachtell Lipton is very much an NYU story.”

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, in his day job at the Seligson firm, Lipton handled new issues of securities for smaller companies, represented clients in SEC enforcement proceedings, and worked on friendly acquisitions in the $5 million to $10 million range. In 1964, the firm broke up, leaving Lipton, Rosen, and Katz to form a new firm. Wachtell, formerly an assistant US attorney for the Southern District of New York, had already struck out on his own as a litigator. In January 1965, the four men, joined by Jerome Kern ’60, hung out a shingle, though Kern would leave in a few years to become an investment banker. All of the original men, including two young associates, had gone to NYU Law.

They started with $110,000 in capital, about $800,000 in today’s money. It was enough for seven lawyers to get along for one year, assuming no business came along. But some business did come along, and Lipton, confident of the future, developed a vision for what kind of firm he wanted it to be. It was Lipton, say his contemporaries, who was most responsible for establishing the firm’s culture and value system. Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz would pursue only the highest-caliber matters. When it came to work and profits, the lawyers would share and share alike. There would be no eat-what-you-kill policy, with each lawyer out for himself. Internal competition was frowned upon. No one spoke of clients in terms of “my client.” All clients were “firm clients.” This tightknit culture of trust was built into the structure of the firm.

A couple of years into Wachtell Lipton’s existence, a disagreement arose between the firm and one of its biggest clients, Metromedia. The firm differed with Metromedia’s founder, John Kluge, on a matter of strategy. Rather than kowtow to Kluge, Lipton simply resigned the account. “He said they could take their business elsewhere,” recalls Bernard Nussbaum, a longtime Wachtell Lipton partner who served as White House counsel to Bill Clinton. “I couldn’t believe it. Here was a client that accounted for maybe 40 percent of our revenue. So I approached Marty and said, ‘What are you doing?’ Marty just laughed. He told me not to worry, that we’d do better next year than we had this year, and of course it was true.” Lipton refused to sacrifice the firm’s freedom of judgment, Nussbaum says, and that integrity led to the success of the firm. “Wachtell is known for making a lot of money,” he added, “but money was never the driving force.”

That integrity quickly became part of the firm’s brand and a reason many corporate leaders would feel comfortable putting their business in Lipton’s hands. “High-powered CEOs are used to manipulating people to get the answers they want,” says Kenneth Langone, a longtime friend of Lipton’s. “You’re not going to get that from Marty. If what he thinks you want is wrong, or borders on unethical, you don’t get him. Everyone’s out there kissing someone’s ass. That’s not Marty’s style.”

Lipton says clients don’t care if you play golf or are entertaining at dinner. “What they’re interested in is whether you’re dedicated to giving them the advice they need to get their deals done on terms that make sense,” he says. “You can’t cater too much to a client and expect to be successful.”

By the mid-1970s, starting attorneys at Wachtell Lipton were earning $22,500, making it one of the few firms paying lawyers more than the going rate at Wall Street firms. Daniel Neff, now a well-known M&A partner and co-chair of the executive committee at Wachtell Lipton, joined the firm in 1977. Neff says Lipton has kept in place a compensation system that has Lipton “dramatically under-compensated” relative to his value. “If,” says Neff, “the 82-year-old senior partner, the guy who had the most to do with creating the firm, is going to be continually underpaid in order to maximize the chance of having a lasting institution, well, that creates a real sense of firm, that we’re in it together, and it becomes pretty clear how you should conduct yourself.”

“We work harder than most firms,” says Jodi Schwartz LLM ’87, a tax partner. “It’s different here. For one thing, you don’t have six dedicated associates to do all your work. We’re at the office doing it with them. Marty has infused this firm with the idea that law is above all a profession, not necessarily a business. Giving back to your school and to the city—these are parts of the profession. He’s someone who leads by example.”

Today, Wachtell Lipton employs about 250 attorneys, making it tiny compared with other firms of its stature. Wachtell Lipton may be a firm of devoted professionals, but it’s a pretty good business, too. In 2012, the American Lawyer ranked it No. 1 in profits per partner, with a “PPP” of nearly $4.5 million, about three times the average among top 100 firms.

Born in Jersey City, New Jersey, in 1931, Martin Lipton was the son of a factory manager and a housewife. Lipton’s father wanted him to go to the Wharton School and become a banker. But when Lipton graduated from Penn with a degree in economics, entry-level Wall Street jobs were different than they are today. “You didn’t just walk into an investment bank and say, ‘I want to be an associate,’ as you do now,” Lipton recalls. “There weren’t these great jobs for aspiring bankers. All you could get was being a registered rep or salesman of one kind or another. I thought what I’d really like to be is a lawyer. I did OK on the LSAT, and there I was.”

For an Ivy League graduate, NYU School of Law was not an obvious choice. Back then the Law School had only about 600 students in total. Its reputation was that of a commuter school for kids from working-class families. Lipton chose NYU partly because Arthur T. Vanderbilt, its visionary former dean, was the chief justice of the Supreme Court in Lipton’s home state of New Jersey. When Lipton started at NYU in the fall of ’52, Vanderbilt Hall, the school’s main building on the south side of Washington Square, had been open for one year. But Vanderbilt, who had been dean from 1943 to 1948, wanted more than physical expansion. His ambition had been to transform the Law School into a top national institution. So focused was Vanderbilt on ensuring the school’s future that he purchased the C.F. Mueller Company in 1947 on the Law School’s behalf, with the intention that the pasta maker’s profits would sustain the Law School. “I didn’t know it then,” says Lipton, “but I would in the future fit as a cog into Vanderbilt’s dream.”

One key aspect of that dream was the Root-Tilden Scholarship Program (now Root-Tilden-Kern, after Jerry Kern, one of the original WLRK partners). It provided full tuition plus room and board to two exceptional college graduates from each of the country’s then-10 federal judicial circuits. During his first year at the Law School, Lipton lived at home and commuted. In his second year, he was taken into the Root-Tilden program and moved to Hayden Hall.

Vanderbilt conceived of the Root-Tilden Scholarship Program in the 1940s because he was troubled that some of the best students and lawyers had become more concerned with making money than they were with participating in American democracy. He wanted to create leaders of the bar who would give unselfishly to serve the public. He named the program for alumni Elihu Root and Samuel Tilden. Root, class of 1867, had been secretary of war under President William McKinley and secretary of state under Theodore Roosevelt. In 1912 he won the Nobel Prize for his contributions to international law. Tilden, class of 1841, was governor of New York and ran for president against Rutherford B. Hayes.

The program at inception was designed to build the reputation of the Law School while also bolstering legal education. So, the scholars were required to take special courses in the humanities, social sciences, history, and natural sciences. They also had to live together and to have lunch and dinner as a group five days a week. To instill Vanderbilt’s values of public service, scholars met regularly with leaders in government, industry, and finance. “The original idea was to bring in people who would have the highest respect for the laws of the country, and who would uphold them in the most ethical manner,” said Thomas Brome ’67, a Root alumnus, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the birth of the program in 2002. “These men would live together and dine together, forming a community of scholars who were infused with interests beyond the mechanical practice of law.”

These were heady, inspirational times to be a law student at NYU. Until then, NYU had been a little-noticed school. But Lipton began seeing his peers benefit from its rising status. In 1954, when the inaugural Root-Tilden class graduated, it was the first time in years that NYU students were hired by major Wall Street law firms. Cravath hired two Root-Tilden Scholars in the class ahead of Lipton. “That was a big deal,” he remembers. “It was some combination of everyone thinking, We’re going to break into the big time and be one of the major law schools. You’d read things about how competitive law schools were. That was not NYU. Everybody was working toward a common goal of providing a professional education and helping other people get along in life.”

Herb Wachtell was a member of that first class of Root-Tilden Scholars. “I remember a tall, skinny guy who wrote a Law Review piece that I proceeded to edit,” says Wachtell, of meeting Lipton. Lipton, likewise, remembers: “My lifelong friendship with Wachtell got off to a rocky start when he took the first note that I wrote for the Law Review and completely rewrote it, pounding away on an old manual typewriter amidst a constant stream of criticism.”

Lipton says his early years of teaching were a catalyst for his future involvement with NYU at increasingly higher levels. Had Dean Niles not targeted Lipton to come back and teach, it’s possible that NYU, without Lipton’s leadership, would look very different today. Evan Chesler, the chairman of Cravath, graduated from NYU and its law school and now sits on the boards of both. He recalls taking Lipton’s class as a third-year law student. “His firm had been having a meteoric rise,” says Chesler. “Marty was already an extraordinarily successful lawyer around town. I remember thinking that it was a big deal to learn securities law from him.”

Chesler adds: “My own view is that Marty feels about NYU the same way I do. He believes the school gave him a life. He’s been one of the leading corporate lawyers in America for half a century. And without that piece of paper from that little commuter law school, which was always hitting above its weight, it might not have been.”

In addition to being an adjunct professor, Lipton added the roles of Law School trustee and president of the Law Alumni Association in 1972. As trustee, Lipton was reunited with his old boss Judge Weinfeld (who would soon become chairman of the Law School’s board) and began consulting closely with Dean Robert McKay on strategy and alumni matters.

These were dire years for the University—and for the city. In 1971, NYU was running a deficit of almost $7 million and hemorrhaging money. Two years later, NYU sold its University Heights campus in the Bronx for $62 million, but by then the NYU budget deficit was around $10 million a year.

“When Marty first got involved, the University was facing hard times,” says William Berkley, founder of W.R. Berkley Corp., the $5 billion insurance company. Berkley got his undergraduate degree from NYU in 1966 and is now a vice chair of the University’s board. “We had given up the engineering school along with lots of other things, shrinking in order to survive.”

One more lucrative asset remained—the C.F. Mueller Company. Vanderbilt had intended its profits to support the Law School, and Lipton believed it was time to sell it for the school’s sake. But there was one snag: The Law School had not been a separate entity from NYU when it purchased the pasta company. So the title to Mueller had been taken in the name of the University, with ownership “for the exclusive benefit of its School of Law.”

On the Law School’s behalf, Lipton tried to negotiate with the University president, James Hester, to obtain direct ownership of the macaroni giant. He was stonewalled, however, until a new University president, John Sawhill, took over in 1975 and appointed Laurence Tisch, then a member of the University board, to negotiate the sale of Mueller on behalf of the board of trustees. Lipton and Tisch sold Mueller to Foremost-McKesson for $115 million. The proceeds were divided between the Law School ($67.5 million) and the University ($47.5 million). An ensuing agreement between the Law School and the University—known to this day as the Treaty—provided that the Law School would not be disproportionately taxed for University overhead and that it would be able to nominate four trustees for election to the University’s board. Lipton, meanwhile, deepened his involvement with his alma mater by becoming one of those University trustees in 1976. In 1978, Lipton was instrumental in Tisch’s being elected chair of the board.

Around the same time, another major institution called on Lipton for help: New York City itself. During the city’s fiscal crisis of the mid-1970s, its comptroller, Harrison Goldin, retained Wachtell Lipton as an adviser. For the final six weeks of 1975, the firm drew on every lawyer in its ranks to work with investment banker Felix Rohatyn and obtain federal financing to restructure New York City’s debt, ending the fiscal crisis. Lipton’s reputation grew.

In 1982, Lipton was in conversation with Arthur Fleischer and Stephen Fraidin, partners at rival law firm Fried Frank. Fleischer and Fraidin represented Burlington Northern, the railroad conglomerate, in its bid to acquire El Paso, a natural gas producer. El Paso’s board of directors hired Lipton to defend against the takeover. “Marty told us that he was going to deploy what would become known as a ‘poison pill’ to deal with our takeover bid,” recalls Fraidin, now a partner at Kirkland & Ellis. “I listened to him describe it and thought to myself, There’s absolutely no way a court is going to uphold this.”

To understand the evolution of Lipton’s career, and why he holds the beliefs he does about how companies should be managed and merged, it’s necessary to know a little about the way the world of mergers and acquisitions morphed during the second half of the 20th century. When Lipton began practicing corporate law, M&A had been limited mostly to so-called strategic deals: If it made good business sense for one company to buy another, then the prospective buyer would approach the board and seek 90 percent of the shareholder vote. In the 1970s, a new approach to taking over a company, considered déclassé by New York’s older white-shoe firms, came into vogue: Corporations were using hostile takeover bids and proxy battles to win control of other public companies. These deals were “hostile” because they excluded the board of the target company and coerced the target’s shareholders. The dominant technique was the front-end-loaded tender offer, in which the hostile bidder makes an offer for 51 percent of the shares, with a statement that if the bidder acquires 51 percent within 10 days, then it will force a merger. Those shareholders who don’t tender their shares on the “front end” will get a lower price, or might just wind up holding debt, an IOU.

“In a sense, this made the transaction involuntary, because shareholders had to get in on the front end,” explained William Allen, Nusbaum Professor of Law and Business, who in the 1980s and 1990s sat on Delaware’s Court of Chancery, a leading trial court for business law. At the same time, says Allen, evolution in the money markets had made large pools of capital available to entrepreneurs. The new breed of company buyers, typified by T. Boone Pickens and Carl Icahn, worked outside the establishment of big investment banks. Known as financial buyers, these new entrepreneurs looked to buy companies based not on their strategic relevance but on the financial return to be made if they could buy the company with borrowed money, fix its capital structure, and flip it for a profit.

These corporate raiders upset two powerful groups: corporate management, who were losing control of their firms, and labor unions, who often saw jobs slashed and factories closed when financial buyers moved in. Political power amassed on the side of wanting to slow these hostile tender offers. In this new environment, lawyers came to the foreground, offering either offensive or defensive tactics. Lipton frequently tussled with the legendary offensive lawyer Joseph Flom of Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom.

Eight years Flom’s junior, Lipton had won attention in 1974 for an offensive role, representing Loews in its hostile acquisition of the CNA insurance company. But the following year, Lipton established his reputation as a defender of corporate boards when squaring off against Flom on a high-profile deal, Colt Industries’ $151 million takeover of gasket-maker Garlock. The Garlock deal was documented in detail in a 1976 New York article, “Two Tough Lawyers in the Tender-Offer Game.” The piece was written by Steven Brill, who would later create a legal-media empire that included American Lawyer and Court TV. Comparing the two attorneys, Brill described Lipton as “huskier and slightly better tailored, in his habitual white shirt and black suit, and wearing bottle-thick glasses.”

As a defender of companies in hostile deals, Lipton sought to return power to management by slowing the takeover process and forcing bidders to negotiate directly with the board. His signature invention was the aforementioned poison pill, which he developed between 1980 and 1982. The pill is triggered when a shareholder—a potential bidder for the company—acquires 20 percent of the shares. At that point, the other shareholders have the right to buy up more shares at a discount. This in turn dilutes the bidder’s interest and raises the cost of acquisition. It’s called a poison pill because it makes the company temporarily “sick,” unattractive to the bidder.

When Lipton explained his idea during Burlington Northern’s bid for El Paso, Fraidin figured a court would deem it illegal because the poison pill, after all, required that a board exclude the bidder from the self-tender. Critics also argued that it interfered in a transaction among shareholders and would be used by boards to entrench themselves in management. But in 1985, the Delaware Supreme Court upheld the poison pill as a valid takeover defense, sealing Lipton’s reputation as a brilliant corporate M&A strategist.

What’s unique about Lipton’s stewardship of NYU is not just the depth of his involvement—it’s not unusual for successful alumni to become benefactors and trustees of their alma maters—but also that he has managed to put his dealmaking prowess to work at so many decisive junctures for the university. Two decades after he helped sell off the Mueller company, buttressing the financial security of the Law School and the University, Lipton turned his attention to the problems of the NYU School of Medicine and Tisch Hospital, caused, he says, by the growth of managed healthcare.

In 1997, Lipton attempted a merger of Mount Sinai Hospital and the NYU Medical Center, which encompasses four hospitals and the medical school. By this time, he had further ascended the NYU ranks. In 1988, Lipton was elected to succeed Judge Weinfeld as chairman of the Law School board after Weinfeld died. Then, when Larry Tisch retired as chair of the University board in 1998, he recommended Lipton as his successor. “It’s not that I think I’m too old to continue as chair,” Tisch said at the meeting, “it’s that I’m afraid Marty is getting too old to succeed me.” (Tisch passed away in 2003.) The proposed hospital merger, Lipton’s first major test as leader of NYU, was critical for the future of the medical school, but it soon became problematic. First, the faculties of the medical schools of both organizations opposed the merger, and the plan was abandoned. Eventually the merger went through, but then the entities had to be de-merged, in 2001, when financing that had been promised by Mount Sinai fell apart. Lipton faced the possibility of an embarrassing failure.

For another NYU chair, the situation might have been overwhelming. For Lipton, drawing on four decades of M&A experience, it was nothing new. When the hospital merger caved, he approached his friend Kenneth Langone about taking on the chairmanship of the Medical Center and working to resolve its problems. “We were facing considerable difficulty,” Lipton remembers. “When you’re in a situation like that, you try to think who it is that you could turn to to be effective. I thought, If I could get Ken to put the kind of enthusiasm into this that he puts into everything else he does, it’d be perfect.” Langone said he

wasn’t interested.

“Ken, let me level with you,” Lipton recalls saying to Langone at the time. “I’m desperate. Will you at least come down to the Medical Center and meet some of the people?”

Langone visited the Medical Center—twice—and then Lipton paid him another visit at his office. “He said to me,” remembers Lipton, “‘I decided I’m going to do this. And you know, Marty, I never put time into something I can’t invest in.’” Langone handed Lipton a check for $100 million.“Why did I do that?” Langone asks. “Simple: Because Marty Lipton asked me to. If the tables were turned, he would have done the same for me.”

Of course, this sounds too simple in the retelling, but as William Berkley, the insurance mogul who sits on the NYU board with both men, explains: “You trust Marty for a couple reasons. First, he’s balanced. He says, ‘What does the other side need and what do we need, and how do we move forward?’ He’s not about pie in the sky. He’s about reality. Second, he’s got this strong emotional commitment to NYU. No one can debate that. He’s so committed because of his experiences at the Law School, which were clearly just really extraordinary for him. Marty thinks of it as his family, something he’s indebted to. He believes it’s an absolutely integral part of his life.”

In the past, Lipton has said that he never questions what he’s doing with his life, or how he chooses to spend his time. “You don’t have to plumb to the depths of my psyche,” he told the New York Observer in 2005. “There’s nothing there.” It’s not surprising, perhaps, that someone who has worked so hard at the same tasks for so long isn’t prone to much existential angst. But the epic course of Lipton’s career, split between his firm and his school, suggests a deep soulfulness that he probably would never admit to.

University President John Sexton, whose ascendant career at NYU parallels Lipton’s—Sexton became dean of the Law School shortly after Lipton became chairman of the Law School board—says the two men “consider each other brothers” who share an “extraordinary friendship” that has spanned nearly 30 years. “It’s fair to say there isn’t a single person who has entered Marty’s life, either in a personal or professional way, who hasn’t felt enhanced by his presence. He is an extraordinary embodiment of the ideal of care and caring.” Sexton also expresses appreciation for his and the University’s partnership with Marty. “He’s one of the busiest people in the world,” says Sexton, “and yet never has a call from me or anyone associated with NYU gone for more than an hour without an answer. When he’s asked to do something, it’s done immediately.”

Over the decades, that commitment amounted to incalculable and invaluable non-billable hours. But asked about his legacy, one of the most famous corporate lawyers in America looks away and shrugs, a little embarrassed. “There’s nothing else more important in life,” he says, “than what one achieves by contributing to the welfare and the benefit of those who come after us.”

—Dan Slater, a former litigator, is a freelance journalist and author of Love in the Time of Algorithms: What Technology Does to Meeting and Mating.

—