His First Century

Printer Friendly VersionIn Jerome Bruner’s 100th year, he whispers the lines of T.S. Eliot, revisits the loss of his father in childhood, and talks about the sources of human happiness and misery. And then he weaves these strands of thought together as if they were one.

In an afternoon chat, Bruner, one of the most influential psychologists of the 20th century, is every bit the acrobatic meta-connector of ideas that most anyone who has ever known him suggests.

“My lawyer friends say to me, ‘You’re always asking these goddamned impossible questions,’” says Bruner, his hands flying as he sits amidst his three desks and thousands of books in his Mercer Street home. “And they are pretty much impossible. But the search for the impossible is part of what intelligence is about.”

His lawyer friends, along with his education friends and psychology friends—15 colleagues from institutions around the world—are marking his momentous October 1 birthday with a collection of essays, Bruner Beyond 100: Cultivating Possibilities. They call him a “Pied Piper of interdisciplinary wonder.”

Bruner was born blind but had his sight restored at age two. His father died when he was 12, a hurt that endures. Before he died, the watchmaker father sold his company to Bulova, leaving his son a “rich kid,” a fact which he tried to hide. A Duke undergraduate and Harvard PhD in psychology, Bruner co-founded the Harvard Center for Cognitive Studies, which favored the study of the human mind over pure behavior. When offered a chaired position at Oxford, Bruner sailed his boat across the Atlantic to get there. He was the brains behind Head Start, the federal preschool program, and scholars have called his influence on the ways of learning “epochal.” He has written 15 books.

Nearly all of that occurred before Bruner arrived at NYU Law in the 1980s. That was around the time Peggy Cooper Davis, now John S.R. Shad Professor of Lawyering and Ethics, heard Bruner give a talk. She was struck by how Bruner’s musings across many disciplines could enrich the teaching of law. She sought out University Professor Anthony Amsterdam.

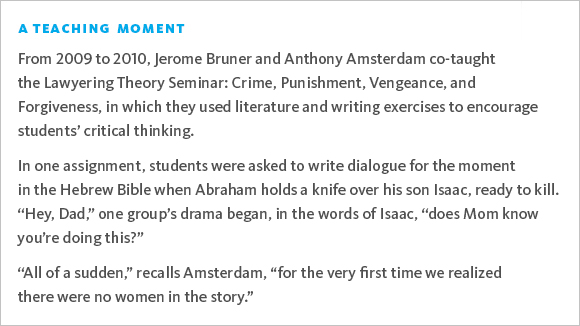

Amsterdam had started the Lawyering Program to help first-year students role-play as lawyers and advance their critical thinking. He had grown interested in storytelling. Bruner, he learned, was well versed in literary theory, culture, and linguistics.

Bruner, meanwhile, was ready for change. “I find a great many psychologists to be rather dull,” says the psychologist, who leans forward for emphasis. “They want to turn mysteries into the obvious.”

And psychology failed to look at how societies create social norms. The law, on the other hand, takes human passions, such as vengeance, and tries to codify them into rules about crime and punishment, often harshly. That intrigued Bruner.

In 1991, Bruner was appointed a visiting professor, and seven years later, University Professor.

Co-teaching with Amsterdam, Davis, and Russell D. Niles Professor of Law Oscar Chase, Bruner drew on cognitive theory, literary criticism, and cultural anthropology, helping colleagues and students examine the humanistic in legal practice.

In the classroom, the law professors employed everything from Greek tragedy to modern-day murder mysteries, leading to transformative teaching. “It was more fun to see them together than it was to see a Broadway show,” says Philip Meyer, a law professor at Vermont Law School who coordinated the Lawyering Program in 1987-88 and wrote a 2014 book, Storytelling for Lawyers, that devotes a chapter to his colleagues. “They played against one another in this delicate, intellectual, cosmic play.” Amsterdam drilled “into and through things,” while Bruner “built these marvelous transitional bridges with complete eloquence.”

Based on their teachings, Bruner and Amsterdam collaborated on a groundbreaking 2001 book, Minding the Law, a study of the law as a reflection of storytelling, culture, language, and thinking. For Amsterdam, the highlight was simply talking with his dazzling friend over sandwiches before the seminars they co-taught for more than 20 years, ending in 2010: “The high point of my intellectual life.”

Hearing this, Bruner turns almost bashful: “That kind of brings a tear to my eye.” He returns to Eliot. “I grow old…I grow old,” he recites, then stops. “You know, all through my career, the literary was never absent. It’s what joins us as human beings.”

—

Multimedia

Multimedia