Ahead of the Curve

During a time of great change for the legal profession, Trevor Morrison is leading NYU Law into the next era of legal education.

Printer Friendly VersionAt the beginning of this year, Trevor Morrison was teaching a constitutional law class at Columbia, training for a marathon, and participating in rounds of job interviews for the deanship at NYU School of Law. But when a colleague found herself unable to teach her con law class for personal reasons, just three weeks into the semester, Morrison didn’t hesitate. Because the two courses were held at the same time, he offered to merge the classes, doubling his own to 193 students. The students were, understandably, nervous and concerned. “I was not happy at the time at all,” says Gabriel Unger, a 1L who was among the transplants. “I felt like we were kind of getting shafted.”

The son of a teacher, Morrison did his utmost to set the new students at ease, welcoming them, reviewing material he’d already taught, and taking questions. At one point, he mentioned turtles in passing, and only half the class laughed. Morrison quickly described the reference to the newcomers: An old woman explains to a scientist that the earth is a flat plate supported on the back of a giant turtle. When the scientist pushes back, asking what the turtle is standing on, he’s told, “It’s turtles all the way down.” The punch line became a bonding point throughout the semester. Morrison did much more than tell jokes, however. He held weekly review sessions, hired three teaching assistants (the first he’d ever used) to offer extra hours, hosted a series of happy hours, and agreed to grade the original and transplanted students on separate curves.

By semester’s end, Morrison had won over skeptics like Unger. “Professor Morrison was an absolutely incredible professor, among the best I’ve ever had,” he enthuses. “He’s clear, organized, engaging, and interesting.” Henry Monaghan, a professor of constitutional law and federal courts who taught Morrison when he was a student at Columbia, praises Morrison for his “lightning-like willingness” to merge the classes, adding, “He is somebody who pitches in for the school.”

Morrison was collecting fans at NYU as well. When the Law School began looking for a dean last November, it cast a wide net, interviewing non-academics, CEOs of corporations, and entrepreneurs, among others. The committee eventually winnowed the field to four candidates and Morrison emerged as the clear favorite. “We found no one else who commanded the kind of universal respect and devotion that Trevor does from an amazingly wide range of people, both inside and outside the academy,” says Daryl Levinson, David Boies Professor of Law, who headed the search committee. “Everyone who has ever met him or worked with him talks about his judgment, wisdom, and ability to bring people together.”

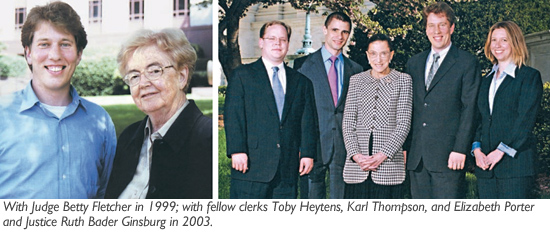

The new dean has accomplished that feat across a range of impressive career moves. Upon graduating from Columbia Law School in 1998, he clerked for Judge Betty Fletcher of the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit and, four years later, another trailblazing female judge: Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. He then entered academia, joining the faculty at Cornell Law School and, five years later, Columbia. He took a year’s leave of absence to work on issues of national security for the White House counsel during President Barack Obama’s first year in office. (He also found time to help vet the nomination of Sonia Sotomayor to the Supreme Court.) At 42, Morrison has already grappled with some of the most urgent legal challenges of our time. He is considered one of the nation’s foremost scholars on constitutional structure and executive powers. “He’s been a first-rate legal scholar whose work shows the kind of intellectual power, subtlety, and sophistication that he will bring to the role of the dean. He’s deeply thoughtful and able to see down the road at an appropriate distance to make decisions that will endure as the correct ones over time,” says Richard Pildes, Sudler Family Professor of Constitutional Law. “He was destined to become the dean of one of the top law schools in the country, and we were very fortunate to be able to persuade him to come here.”

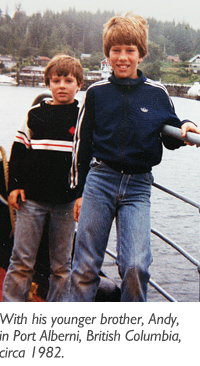

MORRISON’S FATHER, from New Zealand, and his mother, from California, met in college in Seattle, married, and followed jobs to Port Alberni on Vancouver Island in British Columbia. Port Alberni is a city at the head of the Alberni Inlet, surrounded by mountains and forests of red cedar and Douglas fir; many of the parents of Morrison’s friends worked in the paper mills or logging divisions that constituted the small town’s main industry. His father, Hugh, taught elementary and junior high school, and his mother, Anne, did a combination of social and community-building work. Other than one distant cousin, there were no lawyers in the family.

MORRISON’S FATHER, from New Zealand, and his mother, from California, met in college in Seattle, married, and followed jobs to Port Alberni on Vancouver Island in British Columbia. Port Alberni is a city at the head of the Alberni Inlet, surrounded by mountains and forests of red cedar and Douglas fir; many of the parents of Morrison’s friends worked in the paper mills or logging divisions that constituted the small town’s main industry. His father, Hugh, taught elementary and junior high school, and his mother, Anne, did a combination of social and community-building work. Other than one distant cousin, there were no lawyers in the family.

Morrison went to the only public high school in town and excelled at parliamentary debate, thanks largely to prep sessions with his father, who pushed him to think critically. When not studying or working or practicing piano, he ran, choosing the University of British Columbia in part because it had track and cross-country teams with some of Canada’s best middle-distance runners. He made varsity on a seven-person cross country team in which the top runner qualified for the Olympics. (Golf, he admits, is his new obsession.)

He planned to get a law degree and a PhD in Japanese history at Harvard, but a conversation with a graduate student in Japanese studies at Columbia—Beth Katzoff—convinced him to choose the New York City school. After completing a year of the doctoral coursework, Morrison started the JD program there. He became fascinated by virtually everything about the law, which seemed to offer much greater scope for engagement in the world than the narrow set of legal historical questions he was exploring for his PhD. “He was the most frequent attender of my office hours,” says Deirdre von Dornum, who was his TA at Columbia Law School. Von Dornum recently left the Federal Defenders of New York to become the new assistant dean of the Public Interest Law Center at NYU. “He always had a million hypotheticals and he was generally interested in playing out each one far beyond what everyone else was, to understand every aspect of it.” Morrison abandoned the PhD but gained a wife in Katzoff.

After getting his JD, he began clerking for Fletcher and quickly became an expert among the clerks in the knotty questions raised by the law of habeas corpus, which guarantees a prisoner the right to be brought before a judge to determine whether his or her detention is lawful. “The whole group looked to him, and the judge quickly recognized that he could be relied upon for the most cogent and trustworthy of analysis,” says Alison Nathan, a US district judge for the Southern District of New York who also clerked for Fletcher and who later worked with Morrison in the White House. Among the habeas cases, he was drawn to those involving the death penalty, an interest he maintained while teaching at Cornell Law School years later.

Fletcher was an inspiration to Morrison. After having four children, she enrolled in law school, graduating at the top of her class. No law firm wanted to hire a woman—“Prejudice came down on me like a ton of bricks,” she later wrote—but she finally convinced one to hire her, becoming its first partner, the first woman to head the local bar association, and the second woman appointed to the Ninth Circuit. She went on to write some 700 opinions, including one in 1984 approving affirmative action for women in Santa Clara’s transportation department and another in 2007 tossing the Bush administration’s fuel-efficiency requirements for light trucks and SUVs because Fletcher found that the rules failed to adequately account for global warming. Her liberal record made her a target of conservative senators, who forced her to take senior status in 1998 after Bill Clinton appointed her son to the same court. Unlike most senior judges, however, she never reduced her caseload, ruling in more than 400 cases a year before her death last year at the age of 89.

Her work ethic left a lasting impression on Morrison, who said she expected equally dedicated service from her clerks: “The judge taught me that a progressive approach to the law can often just be a matter of working very hard. It doesn’t just matter how smart you are.”

Morrison never forgot the lesson. After stints at the US Office of Legal Counsel, the Solicitor General’s Office, and Wilmer, Cutler & Pickering, Morrison returned to clerking in 2002, for an admirer of Fletcher’s, Supreme Court Justice Ginsburg. At the same time, he went on the teaching market for law professors and juggled the demands of his newborn daughter, Clio. (Daughter Sophia was born five years later.) “I’m not sure he slept,” says Toby Heytens, his co-clerk who is now a professor at the University of Virginia School of Law. Despite the grueling schedule, Morrison nearly always made time for the pickup basketball games that took place on a court above the courtroom. As Heytens puts it: “No matter how busy he was, Trevor was always in. There were a couple instances where Trevor was playing basketball and the justice was looking for him. He went down to talk to her about a case while wearing gym shorts and a T-shirt.” Ginsburg hasn’t held it against him. As she told the New York Times: “NYU Law School has snared a prize. Trevor possesses in abundance all the qualities needed to make a great dean.”

IN 2008, MORRISON SPENT CHRISTMAS helping to draft executive orders for the newly elected Barack Obama. His work impressed Greg Craig, Obama’s first White House counsel, who asked him to join the office. Morrison had just moved from Cornell to Columbia and had taught only one semester at his new school, but he was drawn to Obama’s ambitious agenda and agreed.

Morrison worked on orders banning torture, including water-boarding, and calling for the closure of Guantánamo Bay. The first was successful; the second, less so. He spent much of his time on a task force charged with figuring out how to reform detention policy, deciding whether, for example, enemy combatants should be tried in military courts or Article III courts. When the president opted to keep the military commissions, Morrison worked to reform them. “He’s able to find common ground between vastly different points of view,” says Brigadier General Mark Martins, who was the Defense Department’s representative. “I remember identifying some really difficult aspect of policy we were going to deal with. I laid out the tensions on all sides. After about a 20-minute rundown of the difficulties, he said, ‘That’s just the needle we have to thread.’” And thread it, they did. Morrison became a regular presence on Capitol Hill, talking to staffers and helping to find the votes for the White House’s vision. At a time when not a lot of legislation was passed, the Military Commissions Act of 2009 did.

At year’s end, Martins invited him to spend a year in Afghanistan to help implement detention reforms similar to those they had addressed on the task force. Morrison felt compelled to decline. Commuting between Washington, DC, and New York City had already imposed enough of a burden on his wife, a librarian at Columbia who specializes in Japanese history, and their two young daughters; Morrison wanted to be home. But when Martins invited him to spend a week in Afghanistan assessing the work of the military boards charged with reviewing enemy combatant detentions there, Morrison readily agreed. He flew to Bagram Airfield, observed the boards, and was largely impressed. As Morrison puts it, “One indicator that the boards’ scrutiny was real was that a lot of people were released.”

At year’s end, Martins invited him to spend a year in Afghanistan to help implement detention reforms similar to those they had addressed on the task force. Morrison felt compelled to decline. Commuting between Washington, DC, and New York City had already imposed enough of a burden on his wife, a librarian at Columbia who specializes in Japanese history, and their two young daughters; Morrison wanted to be home. But when Martins invited him to spend a week in Afghanistan assessing the work of the military boards charged with reviewing enemy combatant detentions there, Morrison readily agreed. He flew to Bagram Airfield, observed the boards, and was largely impressed. As Morrison puts it, “One indicator that the boards’ scrutiny was real was that a lot of people were released.”

Upon returning to Columbia, Morrison didn’t leave government life behind. He helped start a colloquium on national security law and policy, which hosted current and former lawyers in government, including those who had served as general counsel to the Defense Department, the CIA, the State Department, and the White House.

Morrison’s scholarship reflects his experiences as a lawyer. In 2010, for example, he wrote an article published in the Columbia Law Review analyzing the opinions of the Office of Legal Counsel. Drawing on opinions from the Carter administration through the end of Obama’s first year in office, Morrison found that OLC largely followed its own precedents, or the rule of stare decisis. That and other articles by Morrison respond to scholars such as Bruce Ackerman at Yale, who has argued that in the absence of routine judicial review of their work, executive legal offices like OLC cannot reliably place any meaningful check on presidential power. Morrison argues that such critiques are insufficiently attentive to the subtle but important dynamics of government lawyering, and that offices like OLC can and do provide real constraints on the president. The infamous “torture memos” written by OLC lawyers John Yoo and Jay Bybee in the years immediately after the attacks of September 11, 2001, Morrison argues, are anomalous abuses, not business as usual, as Ackerman contends. “This is a very high-stakes debate,” says Samuel Rascoff, an associate professor of law at NYU specializing in national security. “What you think about these kinds of lawyers matters for whether you believe the US is practicing national security under the rule of law. The stare decisis article is classic Trevor in that it’s a defense of the best of what the legal profession has to offer.”

More recently, Morrison co-wrote with Curtis Bradley an article in the Harvard Law Review titled “Historical Gloss and the Separation of Powers,” which challenges the assumption of courts that congressional silence in the face of an assertion of executive power amounts to acquiescence. Morrison also co-wrote an amicus brief defending the constitutionality of the Affordable Care Act. In it, he made the argument that the individual mandate to buy health insurance is a tax and falls under Congress’s tax power. The Supreme Court ultimately upheld the mandate on that ground.

Morrison takes on these sober concerns with a cheerful and energetic spirit. “There’s a wonderful lightness in the way he goes about doing his heavy and important work,” says Olatunde Johnson, a Columbia Law professor who specializes in civil procedure and civil rights. “He will just crack jokes in situations, which helps defuse any bad feelings in the room and helps bring the best out of people.” Ariela Dubler, a Columbia Law professor who taught a seminar on executive power with Morrison, says: “There’s not an academic thought that I’ve not run by Trevor. He reads everything I write. I read everything he writes. He’s gracious and intellectually generous and fun to talk to about ideas and great to teach with.” Sarah Cleveland, a professor of international and human rights law, concedes: “I think he was probably the leading internal candidate to be our dean, if he had stayed here.”

So what’s the secret to Morrison’s success? The ability to thrive on little sleep, with some help. He has skills as a barista that are a fitting testament to his Pacific Northwest roots. “I have a very elaborate espresso machine, and Trevor has tutored me every step of the way,” Dubler says. “He can make the hearts in the milk. He can make that leaf in your foam. I can only aspire to that leaf.” Morrison has had years of practice; every morning, he says, he makes a latte for Beth. (During an icebreaker lunch with NYU Law administrators in the spring, Morrison also confessed that he and Beth watch the romantic comedy Love Actually several times a year.)

IN EARLY APRIL, Morrison e-mailed his students to tell them that he had just accepted the deanship at NYU. “I want to assure all of you that this development will not diminish in any way my complete commitment to our class and to you, my students,” he wrote. Shortly after the official announcement was made, he headed up to Amsterdam Café for a planned happy hour with his students.

Morrison enjoys teaching to such a degree that he refers to it as a “selfish” pleasure. His students at Columbia have responded to his enthusiasm. In 2011, Morrison, who taught federal courts in addition to con law, won the school’s top teaching award. And at a recent auction to raise money for public-interest law, the opportunity for a group of students to have lunch with him and two colleagues was among the top-selling items. This fall at NYU Law, even as he’s learning the ropes of his new position, he plans to teach a con law class to signal his commitment to students.

The new dean will be taking the helm at a time when applications to law schools nationwide have declined amid profound concerns about whether a legal education justifies its cost. Many graduates of the 203 ABA-accredited US law schools cannot find high-paying jobs that will allow them to repay the debt most accrue for their schooling. “There is a general oversupply of law schools structured on the traditional model and, tragically, an undersupply of legal services to the poor, especially in rural parts of the country,” Morrison says. “These are large systemic challenges, but a leading school like NYU continues to have an incredibly important place in American public life and law.

“What our graduates do in the first year after they leave here may not be what they’re doing 10 years later,” he says, emphasizing the portability of the skills law students gain. “They may even move beyond the formal practice of law, but they will still rely on the training they received here in critical thinking, analytical reasoning, and problem solving. Law schools do better than any other graduate program in training their students for a wide range of careers.”

Morrison, whom Columbia Professor Monaghan refers to as a “first-class energizer,” has excited just about everyone he has met at NYU. His academic credentials are beyond reproach. Or as Rascoff puts it, “He does his work with enormous intelligence, the best academic values, and a highly credible golf game.” But how will he fare with the more pedestrian demands of the job?

Jeannie Forrest, a vice dean who was on the search committee and was once associate dean of development, decided to test him. “In the company of several trustees, I said, ‘Ask me for money,’” she recalls. “You have to be nimble to respond to a question like that and to make an ask.” Morrison paused, thought about it, and launched into what Forrest describes as a reasonable pitch. She was impressed. “But what was really remarkable to me was that afterward, when we walked downstairs, he said, ‘How could I have done that better?’” When Forrest relayed his comment to the trustees, they said, “That’s our dean. That’s who we want.”

—Nadya Labi is a writer based in New York.

—