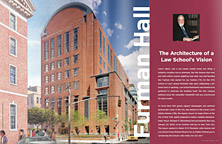

The Architecture of a Law School’s Vision

Furman Hall, the first new construction on campus in 50 years, makes a grand entrance.Furman Hall, the first new construction on campus in 50 years, makes a grand entrance.

Printer Friendly Version

Limos, lights, and a red carpet usually mean one thing: a celebrity-studded movie premiere. But the tuxedo-clad men and well-coiffed women alighting from their cars and heading into Furman Hall, named for Jay Furman (’71), for the NYU School of Law’s annual Weinfeld Gala were celebrating a different kind of opening. Law School luminaries and benefactors gathered to dedicate the building itself, the first campus addition since the venerable Vanderbilt Hall was constructed 50 years earlier.

As more than 500 guests sipped champagne and admired spectacular views of the city, one alumna in the crowd, Carol Robles-Roman (’89), the deputy mayor for legal affairs of the City of New York, quietly prepared to make a surprise announcement: Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg had proclaimed that day, January 22, 2004, to be Furman Hall Day in New York City. The mayor wanted to thank NYU President John Sexton and Law School Dean Richard Revesz for, as Robles-Roman put it, “producing the lawyers who make our city tick.”

Bloomberg was also implicitly acknowledging the building’s symbolic meaning: Furman’s groundbreaking took place as scheduled on September 28, 2001, just 17 days after the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center—the first large-scale construction to begin in the city after that terrible day. “This project affirms our commitment to prepare our students to seek justice through law,” then-Dean Sexton said on that day. “We also reaffirm our University’s resolute commitment to a great city. We build our Law School’s future, as our city must rebuild its future, on a foundation of justice, the bedrock of our republic.” U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who attended the ceremony, echoed Sexton’s sentiments. “The need for lawyers does not diminish in times of crisis,” she said. “It only increases. NYU has played, and will continue to play, an important role in training lawyers who understand the need to convince a sometimes-hostile world that our dream of a society that conforms to the rule of law is a dream we all should share.”

A little more than two years later, their ambitious plan was realized, and clusters of alumni and other members of the Law School’s extended family were touring the state-of-the-art classrooms and checking out the comfortable lounges and clinic offices before heading over to the flower-filled, candle-lit law library in Vanderbilt Hall for the rest of the festivities. The event, by incorporating both sites, was designed to pay homage to the older building’s dedication a half century earlier as well; the new building created a sense of excitement in the reading room, and the grand dame bestowed a bit of gravitas on the upstart across the way. The programs mirrored each other as well. In 1951, the four speakers were: John W. Davis, president of the New York City Bar Association; Roscoe Pound, dean emeritus, Harvard Law School; Sir Francis Raymond Evershed, the Master of the Rolls of England; and Arthur T. Vanderbilt, chief justice of the Supreme Court of New Jersey and dean emeritus of the NYU School of Law. In 2004, the four were: A. Thomas Levin (’67, LL.M. ’68), president of the New York State Bar Association; Elena Kagan, dean of Harvard Law School; the Right Honorable Lord Slynn of Hadley, Law Lord, House of Lords; and Richard Revesz, dean of the NYU School of Law.

Dean Kagan, for her part, underscored her commitment to the psychological cornerstones laid by Roscoe Pound: “Harvard and NYU have followed Pound’s blueprint,” she said. “Go global and keep comparative law at the center.” Kagan also emphasized the value of Furman Hall’s cutting-edge technology and generous allocation of space for international legal studies. “Never has there been a more important time to create the facilities to allow us to connect with opposite shores,” she said. “As a law school dean, I share your joy in this simply splendid achievement.”

RED BRICKS AND GOLDEN SCISSORS: OPENING THE DOORS

“Ours would be an impressive campus anywhere,” said Dean Revesz at the January 12, 2004, ribbon-cutting ceremony. “It’s wonderful to think we have it right here in Greenwich Village.” Furman Hall, at 245 Sullivan Street, between Washington Square Park South and West Third streets, comprises 170,000 square feet, almost doubling the Law School’s space, while the number of students holds steady at around 1,900. Early on, the Greenwich Village community voiced concerns about the building’s effect on the neighborhood, but the Law School, with the guidance of architectural firm Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates, worked with the community and city preservation groups to ensure that Furman Hall reflected the history and feel of the neighborhood. The building’s facade re-creates aspects of the two structures that previously occupied the site: Judson House, an annex of Judson Memorial Church that was renovated by McKim, Mead & White in 1899, and the Poe House, a row house from the 1830s, occupied briefly by Edgar Allan Poe. Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the new building is that it was finished on time and under budget. “We are grateful to the members of the Greenwich Village community,” said Dean Revesz. “They ended up being our partners.”

The dean also expressed gratitude to other key players, including University President John Sexton; Lester Pollack (’57), chair of the Law School’s Board of Trustees; Martin Lipton (’55), former chair of the Law School’s Board of Trustees and currently the chair of the University’s Board; and, of course, Jay Furman (’71), one of the country’s leading real estate developers and the building’s namesake. “Jay contributed not only generous resources,” said Revesz, “but worked tirelessly over several years, with enormous creativity and imagination, to make sure that the project was completed on schedule. Even more to the point, Jay, a devoted alumnus whose generosity has also helped establish our Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy and the Furman Academic Scholarship Program, personifies a love and commitment to learning. No name could fit more perfectly on this structure than his.”

Standing in the bright winter sunlight during the ribbon cutting ceremony on a freezing January morning, Board Chairman Lester Pollack, flanked by festive purple and white balloons, reviewed highlights of the Law School’s history—the creation of the Root-Tilden Scholarship Program, the building of Vanderbilt Hall, the formation of the clinical programs—and added Furman’s inauguration to the list of big moments. “This building,” he concluded, “is an act of transformation.”

Then the speakers lifted a pair of enormous golden scissors and snipped the ribbon, officially opening Furman Hall’s doors. The group, along with students and faculty, headed inside to scatter crumbs and spill coffee (that is, to have breakfast for the first time in the new building) in the John Sexton Student Forum, a cozy lounge with couches and wooden booths. “Furman Hall is firstrate,” pronounced Barry E. Adler, Charles Seligson Professor of Law and associate dean for Information Systems and Technology, as he tried out a booth. “It’s as convenient and functional as it is attractive.”

WIRED FOR THE RIGHT REASONS: TECH SOLUTIONS

Aside from being an enormously welcoming and well-thought-out space, Furman is also one of the most technically advanced educational facilities in the country. Each of the six classrooms is like a mini-production center where lectures and activities can be recorded, edited, and made available on the Web. Instructors use SMART Sympodiums—basically a kind of touch screen with a computer behind it, allowing teachers to easily incorporate computer and DVD elements into their lectures. The Sympodiums also allow annotating and writing on screen.

All nine seminar rooms have built-in fullcoverage miking of both the professors and students, and the four Flexcourts, classrooms with easily changed set-ups that are ideal for various moot court exercises, are equipped with a broadcast-quality video camera, and an on-site control room featuring a production switcher and nonlinear editing system. That means students can simulate a trial, produce a video, and then stream it to the Web. Best of all, the storeroom of old moot court videotapes that could not be accessed efficiently has been replaced by a system where, once captured, the video (and audio) is indexed and saved to a database, from which it can be easily called up and viewed on the Web.

When not in class, students can work and congregate in a multitude of meeting areas, including a study lounge overlooking a garden and several email bars—spots where they can log on and check or send messages. Benches and lounges are liberally scattered throughout the building. The street-level Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz Student Cafe, named for the prestigious law firm that carries the name of four of the Law School’s most distinguished alumni (Herbert Wachtell (’54), Martin Lipton (’55), Leonard Rosen (’54), and the late George A. Katz (’54)) looks onto West Third Street through floorto-ceiling windows. Corridors are intentionally wide so that students can gather between classes, and the building is linked to Vanderbilt Hall through a basement walkway for convenience on cold or rainy days.

“We appreciate the adjustable-height seats in the lecture halls, the amount of space set aside exclusively for students, and the southern exposure in the clinic offices,” said Nicholas Kujawa (’04), then-president of the Law School’s Student Bar Association. “Students clearly were first and foremost in the minds of everyone involved in the creation of Furman Hall.”

“I like the new space very much,” said Burt Neuborne, John Norton Pomeroy Professor of Law and legal director of the Brennan Center for Justice. “The symposium space on the ninth floor where the faculty meets is the clubhouse I always wanted as a kid—only it’s not in a tree. The seminar rooms teach well, and the snack bar serves good coffee.”

VANDERBILT’S LEGACY: A MISSION ACCOMPLISHED

At the Weinfeld dinner, Dean Revesz expressed confidence that Arthur Vanderbilt would have been thrilled by the new building. “Vanderbilt bemoaned the fact that law schools were failing to train students in the various skills essential to the work of a lawyer,” Revesz said. The Jacob D. Fuchsberg Clinical Law Center, named after one of the Law School’s most distinguished alumni who served for many years on the New York Court of Appeals, occupies two floors, neatly addressing that concern. Students here try (and frequently win) actual cases, write legal briefs, and learn how to deal with unpredictable clients. Furman Hall also houses the Lawyering Program, the intensive mandatory first-year research and writing course, encompassing interview workshops, negotiation exercises, and other practical assignments.

Vanderbilt also worried about the lack of instruction in international and civil law, said Revesz, pointing out that the [Gustave (LL.M. ’57) and Rita (’59)] Hauser Global Law School Program is located on the third floor, and attracts more than a dozen leading faculty members from foreign countries to teach courses and seminars at NYU each year. The program funds 10 of the most outstanding young international lawyers to obtain their LL.M. degrees as Hauser Scholars, while also encouraging collaborations on scholarship between full-time faculty and top scholars from around the world.

“Vanderbilt also would be proud if he visited the Lester Pollack Colloquium Room on the ninth floor,” said Revesz, because it addresses that great educator’s assertion that the relationship between law and the humanities was not as strong as it should be. “Surrounded on three sides by terraces, the bright and airy space offers an impressive place for flagship intellectual events of legal academia, including the prestigious Law and Philosophy Colloquium.”

Finally, Vanderbilt articulated his desire for law schools to address problems of the legal profession itself, Revesz said. Administrative offices—including the Public Interest Law Center (PILC)—located on the fourth floor, answer that need. “PILC works tirelessly to ensure that our graduates are able to play leading roles in public service,” the dean said. “We led the way in designing an extraordinarily generous Loan Repayment Assistance Program in the mid-1990s and make enormous efforts to fund students who are interested in summer jobs in the public services.” PILC also administers the Root-Tilden-Kern program, launched by Vanderbilt himself, which celebrated its 50th anniversary this year. A newer initiative, the Global Public Service Law Program, brings lawyers from developing countries to the Law School to help them hone the skills necessary to strengthen the rule of law when they return home.

There is no doubt that adding Furman Hall to the NYU School of Law campus is cause for celebration—and that it would have earned Vanderbilt’s robust approval. “We have lofty aspirations to be not only the leading law school, but also the law school that leads in providing social good—with the education, scholarship, and vision needed to improve our nation and the world,” Dean Revesz said during the festivities. “Furman Hall brings us a great deal closer to this ambitious goal. For that, I am deeply grateful.”