Leveling the Political Field

Printer Friendly VersionIn 1986 Samuel Issacharoff was in Springfield, Illinois, handling an election law case that revolved around restrictions on black politicians. Issacharoff, then 32, had been around these kinds of voting rights cases for a while, finding them not especially exciting—too technical, too many statistics bandied about by would-be experts that tended to dull the brain. But something happened at the Springfield trial that Issacharoff remembers today in great detail.

His lead client, a candidate for Chicago’s city council named Frank McNeil, was on the stand testifying about an at-large election system that essentially worked to keep blacks from obtaining office. The opposing lawyer seemed to find an opening that could spell trouble.

“Is it true, Mr. McNeil,” the lawyer asked, “that the real reason you’re running for office is you want pork to be distributed to your constituency?”

McNeil responded confidently: “If there’s pork to go around, I want my people to get some, too.”

That pithy, off-the-cuff testimony provided an epiphany of sorts for Issacharoff. It disrupted how he thought about election law and how to organize democratic politics. It was the end result that mattered more in these issues, he thought. The courts should perhaps confine themselves mostly to making sure the political process and institutions were open and responsive—not parse each issue through the constitutional prism of individual rights. In short, Issacharoff said, McNeil’s aphorism was sounding right: Let everyone have an equal seat at the table—and the pork would be distributed just fine.

This spare notion would develop into a distinct field of law, known as the Law of Democracy, that attempts to find a unified theory of election law. It was crafted by Issacharoff, Bonnie and Richard Reiss Professor of Constitutional Law (below, left), his colleague Richard Pildes, Sudler Family Professor of Constitutional Law (below, right), and Pamela Karlan, Kenneth and Harle Montgomery Professor of Public Interest Law at Stanford Law School. Their work culminated in a book, first published in 1998, The Law of Democracy: Legal Structure of the Political Process. More than a mere textbook about election law, it was, as one reviewer observed, a statement about democracy in America, including an unusual assemblage of case studies, political theory, political philosophy and American history. They aimed to shape a chaotic set of legal positions into a level playing field and let the politicians play ball.

In just a decade, their ideas implanted themselves in much of the legal community, and electrified law and political science professors across the country. Owen Fiss, the revered constitutional law and civil procedure legal scholar and professor at Yale Law School, who had taught Issacharoff and Karlan, recalls: “It was just the right book at the right time by the right people.” (Fiss remembers how he was on the reviewing committee of the publisher, Foundation Press, when they short-circuited their usual lengthy scrutiny for this book proposal, greenlighting it immediately.) At least half of the country’s law schools now teach a Law of Democracy course. At NYU, Pildes and Issacharoff alternate each year in teaching the course to second- and third-year students, sometimes bringing in speakers, such as the top election lawyers for the Democratic and Republican parties. And in the fall of 2007, Issacharoff and Pildes joined Pasquale Pasquino, a visiting professor of law at the Hauser Global Law School Program, in presenting a colloquium that focused on democracy abroad, Constitutional Democracies.

The course is “wildly popular” with today’s students, says Yale Law School Professor Heather Gerken. “It’s like teaching sex, drugs and rock ’n roll,” she says. “It’s taking all of the pristine principles of constitutional law, like equal protection and First Amendment, and bringing them to the down-and-dirty world of politics.”

Indeed, not many professors sought to teach courses about electoral matters until Issacharoff, Karlan and Pildes’s ideas “revolutionized what was a pretty boring and tedious field before,” says Dennis Thompson, a political philosophy and ethics professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. But in the last decade, Karlan says that a “huge number of people” entered the field, impelled by the textbook and the 2000 Bush v. Gore election debacle. Gerken recalls that legal theorists such as University of Chicago Law Professor Cass Sunstein and Judge Richard Posner of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit “suddenly started writing about election law, this in a field they hadn’t heard of five years before!” Among the professors who used the trio’s early teaching materials: Barack Obama, while an adjunct at the University of Chicago Law School.

Issacharoff, Karlan and Pildes are now recognized as the founding parents of and leading authorities on this fresh view of election law, having converted many scholars to their “structuralist” camp rather than the “individual rights” school. They have been recognized accordingly. Issacharoff, who was lured to NYU in 2005 from Columbia Law, was selected to deliver the Herbert Hart Lecture in May at the University of Oxford, an especially distinct honor in that the lecture is normally presented by a specialist in legal philosophy. In the span of a few weeks in April, Pildes was awarded a highly coveted Guggenheim Fellowship and elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. A frequent network television commentator on election matters, he was nominated for an Emmy as part of the NBC team covering the 2000 election. In 2004, he wrote the prestigious Harvard Law Review constitutional foreword. And Pildes can claim to have conceived two election-related ideas that were later incorporated as doctrine by the Supreme Court—two more than most law professors (more on those later).

Election Law’s Oscar and Felix

For two guys who work together so well, Issacharoff and Pildes are a kind of odd couple of the academic legal world. Issacharoff greets a visitor at his sprawling Upper West Side apartment one winter day, his salt-and-pepper hair slightly askew, dressed in gray sweat pants, blue T-shirt and Asics sneakers, looking as if he’s on his way to a pickup basketball game, which he plays regularly. Pildes, however, schedules his meeting in his fifth-floor office crammed with law review articles and student papers. He is neat and trim, looking like the former competitive runner he was at his Evanston, Illinois high school, and dressed in a pressed green shirt and brown corduroy pants.

Issacharoff answers questions with little hesitation, while Pildes pauses to formulate his responses. The latter says, “I’m much more of the tortured academic, seeing complexity everywhere, more interested in exploring issues than pushing the bottom line very hard. I think Sam’s much more confident, bottom-line-oriented.” That said, Pildes has no hesitation in calling a couple of his friend’s ideas “wacky” and “off the deep end”—which Issacharoff shrugs off as part of academic give-and-take.

They took differing paths, too, to arrive at the same conceptual place. Pildes’s was more theoretical. After graduating from Harvard Law in 1983, he clerked for Judge Abner Mikva of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit and then for Justice Thurgood Marshall on the Supreme Court. (Pildes self-deprecatingly shares the story of how, when he went to Marshall’s office to say goodbye at the end of his clerkship, the justice, a notably moody character, walked past him and said to his secretary’s pleadings, “What’s he want me to do, kiss him on the fanny?”) Pildes practiced a couple of years at Boston’s Foley, Hoag & Eliot law firm before joining Michigan’s law faculty in 1988, where he stayed until 2000, when he moved to NYU’s law school. True to his Hamlet-like decision-making, it took him two years to make the decision to join NYU, and, more recently, two years to decide to turn down Harvard Law to stay.

Issacharoff, by contrast, had rolled up his shirtsleeves working as a voting rights lawyer. He was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, moving to the United States with his family when he was five and eventually settling in Manhattan. He graduated from SUNY Binghamton in 1975, having majored in history, and spent a year studying at the Université de Paris. At Yale Law School, Fiss recalls, Issacharoff “disagreed with almost everything I had to say and yet I hired him as a research assistant and learned from him ever since.”

After graduating in 1983, Issacharoff focused on minority voting rights and labor law at firms and organizations including the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law and the Lawyers’ Committee for International Human Rights. As a law student, he represented clerical employees in front of the National Labor Relations Board in their successful effort to unionize. In 1989, he joined the faculty at the University of Texas at Austin School of Law.

It was at Texas, in 1992, that Issacharoff got an idea (inspired by Georgetown University Law School Dean Alexander Aleinikoff) to organize a conference on government, constitutional law and politics. Among the attendees was Pildes, who had studied electoral topics for years but was, he relates, “groping for a specific way into those issues that seemed fresh, that hadn’t been explored in lots of depth.” Also there was Karlan, then teaching at the University of Virginia School of Law. She had gone to Yale Law School at the same time as Issacharoff, and had met Pildes while both of them were clerking at the Supreme Court, she for Justice Harry Blackmun.

Issacharoff recalls that it became apparent at the conference that they were exploring a new and distinct area of the law, though never stated so explicitly. Pushed by Aleinikoff again, they decided that a good way to organize the still-inchoate Law of Democracy idea was to gather case material that would be used for teaching—material that was to become the core of their textbook.

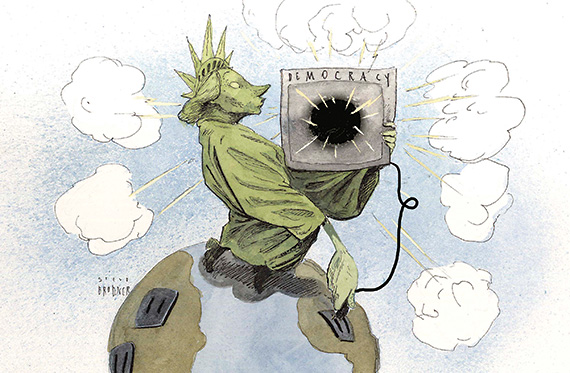

Their timing was exquisite. Democracy and how it should be structured were hot in the 1990s, giving them plenty to chew over. In a series of cases, the Supreme Court raised the visibility of what democracy meant by increasingly applying the Constitution to matters involving redistricting, term limits, campaign financing, and the like. The world, meanwhile, was going through a frenzy of democratization, from the former Soviet Union to Latin America, South Africa and parts of the Middle East. More new democracies were formed than in any comparable period, Pildes points out, raising real-life questions about how to design democratic institutions.

“All of this kept pushing these issues onto the agenda in ways that were not thought about much before,” Pildes says.

The authors were drawn at first to the theories of John Hart Ely and his groundbreaking 1980s book, Democracy and Distrust, according to Issacharoff. Ely worried about overreaching judicial activism, citing decisions like Roe v. Wade, and he tended to put more emphasis on the process of lawmaking rather than on the theory. This was an idea they thought could be carried over to the world of democratic politics: Courts should protect the process or structure of politics—making sure no one was shut out before the first ballot is cast—rather than wade in too heavily to determine what is a “good society.”

A more conservative view, to be sure, but more transformative to society, Issacharoff contends: “More has happened to advance the cause of black people as a result of making sure there is active black representation in Congress and legislatures than as a result of the more aggressive court cases that have sought to deal with things like poverty.”

Issacharoff churned out a series of papers throughout the 1990s as he delved into the topic. In a 1993 Texas Law Review piece (“Judging Politics: The Elusive Quest for Judicial Review of Political Fairness”), for example, he challenged the conventional wisdom that gerrymandering corrects itself. In that view, political parties that attempted to control as many districts as possible risked losing, should a small percentage of voters shift allegiances. In 1995, he set the stage for his argument that the Constitution was limited in analyzing voting rights disputes (“Groups and the Right to Vote,” Emory Law Journal, and “Supreme Court Destabilization of SingleMember Districts,” University of Chicago Legal Forum).

For his part, Pildes explored general constitutional and legal theory in great depth. In a series of articles, he argued against the idea that constitutional rights give individuals absolute freedom. Instead, he proposed that rights should be seen as regulating government actions, limiting the kinds of reasons for which government can act (“Why Rights Are not Trumps: Social Meanings, Expressive Harms, and Constitutionalism,” Journal of Legal Studies,1998). He also turned to less theoretical areas, studying cumulative voting systems in Alabama in a 1995 paper, “Cumulative Voting in the United States,” in the University of Chicago Legal Forum.

A Field of Law?

Defining the Law of Democracy is no easy matter; even Pildes demurred. Yale’s Owen Fiss, who himself teaches a Law of Democracy course, wonders aloud whether the professors have yet to find an “autonomous set of principles” governing election law that would properly constitute a law of democracy, even as he’s convinced that it exists. “The work remains to be done, and that’s the great challenge,” he says.

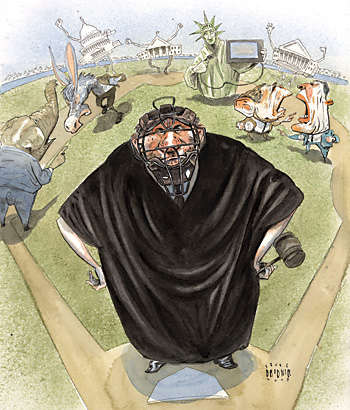

But Pildes and Issacharoff argue that American democratic institutions aren’t fixed in stone, that they are constructed along the way and that self-interested politicians require policing to make sure they don’t gum up the works. “All the issues we identified—like campaign financing, districting—share a common core around the basic questions of what is the point of democracy, what are the objectives of democracy, what are the tradeoffs when designing institutions,” says Pildes.

And as the professors saw it, the Supreme Court certainly wasn’t doing a great job in sorting it all out. The courts’ tendency to apply constitutional law and abstract principles of individual rights to resolve electoral disputes was, they said, mostly a mess. Without a unifying vision, courts created a mishmash of cramped, sometimes illogical rulings.

“Cases that involved campaign finance were treated as First Amendment cases,” says Issacharoff. “Cases that involved redistricting, like Baker v. Carr, would be treated as equal protection.” And the courts threw up their hands in futility when it came to cases testing the power of political parties. “[Individual rights] is an abstract, philosophical way of thinking about these issues that just doesn’t have any traction for dealing with the real-world problems that this area addresses,” says Pildes.

It was better, they said, to think more pragmatically about these matters—meaning to consider the consequences when resolving legal issues surrounding democratic politics. And in weighing those questions, Issacharoff and Pildes suggested separately, courts should view politics not as a clash of states vs. constitutional individual rights, but as a competitive marketplace.

They unleashed this metaphor in February 1998 in “Politics as Markets: Partisan Lockups of the Democratic Process,” published in the Stanford Law Review. Does a law limiting campaign contributions, for example, lead to a robust marketplace of candidates—or does it lock out potential aspirants? By viewing the issue that way, it was no longer a fuzzy First Amendment case about restrictions on political speech. As Burt Neuborne, Inez Milholland Professor of Civil Liberties and legal director of the Brennan Center for Justice, notes, the professors were asking the overlooked yet critical question in election matters: “Is it good for democracy?” Or as Pildes puts it: “I think the fundamental question ought to be, Is this rule a means of stifling political competition or not?”

The backbone to their marketplace approach is this: The biggest threat to a democracy is the tendency for incumbents to lock up the political process so they can’t be effectively challenged. “Inherent authoritarianism,” Pildes calls it.

“The term ‘lockup’ was deliberately chosen,” says Issacharoff, who spent a year at Columbia studying corporate governance theory, “because it’s a term of art in corporate governance law—where management makes it impossible to dislodge it. We were trying to say the same thing happens in the public domain, for example, difficulty in getting a third party at the ballot, difficulty in challenging incumbents in a primary.”

When should the judiciary step in to unlock the door? Judges, they said, should aggressively scrutinize laws such as gerrymandering that appear to entrench and protect politicians. Otherwise, when laws are only reshuffling democratic rule-making—as in those involving primaries, for example, that don’t entrench one set of insiders over another—they should back off. Of course, figuring out where to draw the line here is no easy trick, Pildes says, acknowledging but rejecting critics who say their model will invite an overly aggressive judiciary. He compares the role of courts to a cancer drug, targeting pathology in the democratic system but hopefully not destroying healthy tissue.

The article set off a firestorm. It was, so it seemed, attacking the sacrosanct paradigm of individual rights and substituting a managerial concept, using business school words like antitrust and lockup. Critics said it wasn’t asking enough about what is right or moral. Pildes notes that many scholars “don’t want to think about rights necessarily having trade-offs against other objectives. You know, rights are rights.”

Some very prominent academics fall in this camp. Legal philosopher Ronald Dworkin, while a huge admirer of the two professors, notes that the trend to employ the economic model in legal analysis can indeed be overused. Trying to discern commonality between the wants of voters and consumers can be misleading, he says. Harvard’s Thompson, who makes extensive use of the textbook, likewise cautions: “In the market, if we don’t like a product we can buy a different product. In an election, the competition ends in a decision and we have to buy the product—no matter how competitive it is.”

Neuborne, despite his left-leaning political credentials as a former ACLU legal director, says he wasn’t bothered by the marketplace metaphor. “There’s nothing inherently rightwing about viewing things as markets,” he says. “When there’s market failure in democracy, viewing it as a market is a left-wing thing because it means you have to step in and correct the market.”

Today, says Issacharoff, the politics as marketplace idea is mostly considered conventional wisdom. “We went from being, ‘This is outlandish and ridiculous,’ to ‘This is just old stuff,’” he says, laughing. “I wanted a brief moment when we were ‘sober and thoughtful.’”

Bush v. Gore

If there was ever a time when an ivory tower concept suddenly became relevant to the popular masses, it was the 2000 U.S. presidential election. “Florida 2000 was a perfect storm,” says Issacharoff. The combination of creaking and dysfunctional election machinery in Florida; a form of review that was “nastily partisan”; the inconsistency between the popular and the electoral college votes, and a confident Supreme Court, unafraid of inserting itself into areas given to other branches of government, made election law the top story of every night’s news broadcast. It was also a perfect storm for Issacharoff, Pildes and Karlan to enter the media whirlwind with numerous television appearances. They considered turning their commentary and writings into a popular book on the election that could have elevated their name- and face-recognition in the mass media along with well-known legal experts such as Alan Dershowitz and Jeffrey Toobin. But eventually they decided to write an evenhanded casebook for students and professors called When Elections Go Bad: The Law of Democracy and the Presidential Election of 2000.

Four years after Bush v. Gore, Pildes found himself in the middle of what he calls “Bush v. Gore 2.” He was representing Puerto Rico’s election commission in an eerily similar election dispute that would determine the next governor of the commonwealth. His opponent: Theodore Olson, who was Bush’s lawyer in Florida. The controversy again was over whether certain ballots were valid. “I had this surreal experience of arguing against Ted Olson about what Bush v. Gore means,” Pildes recalls. Olson wanted the courts to intervene to halt a recount and have the ballots thrown out (sound familiar?). Pildes won the case, the ballots were counted and the candidate who benefited, Aníbal Acevedo-Vilá, is the current governor.

Real World Applications

Taught at the Law School by Issacharoff or Pildes since 2002, the upper-level Law of Democracy course starts with issues involving individual political participation—the right to vote, for instance—and then moves on to the role of groups in politics—parties, primary elections and the like. But to some extent, this is a course where the syllabus is ripped from the headlines. Pildes and Issacharoff dive into subjects that are in the news and apply their sometimes-unique perspectives, which are often ripe for debate among their colleagues and even between themselves. This being a particularly engaging presidential election year, there’s no shortage of strong and even clashing opinions.

Voting Rights and Race

The landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965, which prohibited states from adopting policies that disenfranchised African Americans, set up extensive federal oversight of jurisdictions with a history of discriminatory practices. But some 35 years later, Issacharoff and Pildes suggested that federal intervention could be dialed back, because the political process in those states and districts—the marketplace—was now open to minorities. This view, Issacharoff points out, gave integrity to their core argument: Just as courts needed to act when confronting entrenchment, they should back away when the political system was operating fluidly.

That idea came to the fore in the 2003 Supreme Court redistricting case Georgia v. Ashcroft, which Pildes calls the most important decision in a generation on race and political equality. Georgia had a Democratic majority but was trending Republican, so the black Democratic majority put together a deal that slightly diluted the concentration of black majority districts, spreading out votes that would shore up Democratic lawmakers elsewhere. Any diminution of black concentration is a prima facie violation of the Voting Rights Act, however, so the Justice Department objected.

The Court ruled, 5-4, that Georgia’s legislature had the latitude to make the changes. Pildes suggests the Court weighed the case in a pragmatic, process-based way, understanding that blacks had gained political power and thus the Voting Rights Act could be interpreted with more flexibility.

Pildes was able to take special pride in the Court’s reasoning. It explicitly endorsed and cited an idea he had proposed just a year earlier in the North Carolina Law Review. He wrote that because whites were now voting regularly for black candidates, it might no longer be necessary to create a majority black election, as required under the VRA. (Barack Obama is proving the point this year in his ability to attract white voters.)

It was the second time that Pildes’s work turned into court doctrine. In 1993, he and political scientist Richard Niemi of the University of Rochester conceived the notion of “expressive harm” in describing the Supreme Court’s view of the constitutional harm done when designing election districts along racial lines. The idea is that the government can inflict harm not only in concrete ways, but also symbolically through ideas and attitudes it expresses. Creating minority election districts, for example, can send the harmful message that members of the same race always share political views. The notion was subsequently employed by the Supreme Court in cases including Miller v. Johnson in 1995 and Bush v. Vera in 1996, in which the Court ruled that redistricting plans in Georgia and Texas, respectively, were gerrymandered to hurt minority groups.

Following Ashcroft and several other Supreme Court rulings on voting, Issacharoff weighed in with a 2004 piece that also pivoted on the idea that blacks were gaining ground: “Is Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act a Victim of Its Own Success?” Issacharoff’s Columbia Law Review article suggested that African Americans had made such gains in the political establishment that Section 5, which required close federal scrutiny for certain districts, had served its purpose—and in fact might be impeding the nowrobust political process.

Two years later, in 2006, Pildes and Issacharoff testified before Congress when Section 5 was up for renewal. Pildes argued the section ought to be updated to reflect the changed political environment that now allows, for example, black-white political coalitions. “Otherwise, the Act becomes a way of entrenching racial identities and a racially polarized form of politics,” he says. Issacharoff, too, testified that the Act was out of date and voiced concerns that it could be exploited for partisan gain. (Their colleague Karlan disagrees, saying the section is still needed in those local election areas where two strong parties don’t exist.) In the end, however, Congress voted to renew the measure with no changes.

Political Parties

The presidential primary season is an apt real-life lesson for students of the Law of Democracy—and specifically the role of political parties. Notice, says Pildes, how Barack Obama and John McCain generally fared better with open primaries, in which voters were free to choose for which party they want to select their candidate. Hillary Clinton did better when only Democrats were permitted to vote in their closed primaries. With open primaries, we generally tend to get more moderate candidates; close them and we get more extreme candidates.

Pildes’s point: A seemingly small, technical rule governing primaries can have enormous consequences for democracy. So who should set the ground rules when disputes arise involving political parties? Generally, let the politicians fight it out in the public arena, he says. Yet the Supreme Court has been intervening of late, generally barring states from regulating how political parties structure themselves.

In its 2000 decision California Democratic Party v. Jones, for example, the Court ruled California’s open primary system unconstitutional on individual rights grounds—a political party, like a private club, has the right to decide its members and who can vote in its primaries. Pildes says the Court once again was wrong to try to invoke theConstitution to settle a matter that should be subject to the back-and-forth of legislative debate—and one that did not involve entrenching one set of insiders over another. The danger, he says, is that the Court could “freeze into place its own vision of how democracy should function.” Indeed, it’s possible that the Jones decision could make it unconstitutional for states to require parties to let independents vote in their primaries. “That would have far-reaching ramifications for the future of American politics,” he says.

Campaign Finance

As Issacharoff sees it, much to his dismay, today’s law school students are fixated on the need for campaign finance reform—specifically, in favor of public financing. “They are as naïve and myopic as the editorial board of the New York Times on this issue,” he declares. Breaking from liberal orthodoxy, Issacharoff (and Karlan) prefers, in short, that virtually all campaign finance restrictions be thrown out except for those requiring disclosure of contributors. “You raise money any damn way you want,” he says. “The media would expose stuff; I think that’s far better.”

Issacharoff and Karlan described the existing system—which restricts contributions but leaves expenditures wide open—as “taking a starving man to an all-you-can-eat buffet but giving him only a really tiny spoon to eat with.” Their 1999 article in the Texas Law Review, “The Hydraulics of Campaign Finance,” caused a stir with its dim view of campaign finance regulation. Comparing election money to water, they argued that shutting off one avenue only diverts it to another—the unintended consequence problem. Regulate money to political parties and it goes to parallel organizations, like political action groups or independent 527 groups (named for a section of the tax code). “Our view is it’s actually much better if the money goes to the candidate,” says Issacharoff. “Because then somebody running for office is actually accountable.”

If it’s any consolation to students, Pildes thinks Issacharoff and Karlan’s idea is “wacky”; it is closer to Justice Clarence Thomas’s view that the First Amendment’s freedom of speech bars any kind of regulation of campaign contributions. Pildes argues the Supreme Court ought to give room to lawmakers to set rules, given the vigorous public debate on a clearly crucial issue. “The position that the Constitution just cuts that off, and says nothing is permissible in regulating the system, seems to me a very troubling thing in a democracy,” Pildes says. But if legislators make laws that act to entrench themselves, then of course courts should intervene on grounds they are anticompetitive. In any case, Pildes argues that this debate is just playing at the margins until something really radical happens—meaning public financing of elections. But that, he notes, isn’t happening anytime soon.

But Burt Neuborne thinks something radical did happen this year that could have a monumental impact on the campaign finance issue: Barack Obama’s remarkable success in using the Internet to raise vast amounts of money in small increments, an average $91 per person. This form of individual fundraising, if replicated in coming years, Neuborne says, could ultimately negate themproblem of big money’s undue influence on elections. “Technology may solve something that the law couldn’t,” he says.

[SIDEBAR: Neuborne Takes Campaign Financing Reform to the Supreme Court]

Partisan Gerrymandering

After the 2010 census, legislators will sit down to draw the boundaries of state and congressional districts. Lawsuits will inevitably flow, claiming one unfairness or another. Issacharoff thinks the system is absurd. In a 2002 paper called “Gerrymandering and Political Cartels,” Issacharoff suggested that all such plans drawn by insiders are self-evidently unconstitutional. He proposed instead that districting should be taken out of the hands of self-interested incumbent politicians and be placed into an independent commission or even a computer. Many countries, including Great Britain, Canada and Australia, use outsiders for this purpose.

The problem of self-interested districting arises most acutely in bipartisan gerrymandering in which, for instance, incumbent legislators strike deals to put all the Democrats in safe districts and Republicans in others. In New York State, for example, party leaders essentially agree to gerrymander state districts to ensure that Democrats control the Assembly and Republicans, the Senate.

Bringing this system down is tricky. No one is being denied the right to vote, he notes, so it’s hard to claim some individual right has been violated. But Issacharoff says the court should not ask about rights violations, but instead should ask a “process” question: Is it presumptively unconstitutional to give incumbent lawmakers the power to determine electoral arrangements?

Issacharoff concedes his idea to strip lawmakers of districting powers is pushing the boundaries. “Rick has characterized this as an approach that even the Warren Court in its heyday would blanch at,” he says with a grin. To be sure, Pildes generally prefers independent commissions, too. How to get to that goal is another matter. “Sam’s idea that the courts should order this across the country is, to put it charitably, provocative and, to put it in practical terms, completely off the deep end,” he says. It would be far better if popular pressure gave rise to independent commissions, he says, rather than to have it “forced down our throat” by the Supreme Court. On the other hand, Pildes says courts have done “virtually nothing” about partisan gerrymandering—the very essence of politicians locking themselves into power.

Agreeing with Pildes, University Professor Jeremy Waldron, who tends to view electoral issues through a philosophical prism, recommends a system used in his native New Zealand that accommodates the indigenous Maori people, about 10 percent of the population. The problem with ethnic or race-based districting, he says, is “it freezes peoples’ identity or it makes assumptions about peoples’ identity,” he says. In New Zealand, the Maoris are guaranteed an opportunity to vote in specially constructed districts, but every eight years they can select whether to register in the special or a regular district. If not enough Maoris choose the special district, it disappears, and the Maoris are absorbed into the regular district. “This leaves it in the hands of the people concerned,” Waldron says.

Emerging Democracies

Following Bush v. Gore and 9/11, Issacharoff says he and Pildes grew more interested in issues like how to administer a democracy, and how to define and set limits on executive authority. That led them to look abroad. Says Issacharoff, “I realized that I was quite uninformed on how other countries address these issues.”

Issacharoff was not in the dark for long. In a 2007 Harvard Law Review article called “Fragile Democracies,” he explored how democratic countries should deal with serious threats by antidemocratic groups that exploit the electoral arena to push their cause. One need only look at Hitler’s rise using democratic means. And there was plenty to study today—Turkey banning Islamic parties, Israel banning parties that deny the Jewish nature of the state, India removing candidates from office who appealed to religious or ethnic hatreds, and others. In America, courts generally use the “clear and present danger” threshold to weigh government restrictions. Issacharoff suggested that may be too high a bar for less stable countries facing mass threats. Those countries need the ability to crack down on such electoral activity without regard to its imminence. The danger, of course, is a power grab by insiders, and thus he says that his pro-competitive approach “would dictate a great deal of caution.”

Neuborne called the piece a “pragmatic argument for minimalism”—meaning democracies in time of stress could interfere with individual rights, yet they needed to think hard about keeping the change minimal. Still, it was controversial, he says, in even allowing some kinds of abridgments of rights. “I’m an ACLU person, so I dig in and fight,” he says. “But maybe you need somebody like me and, at the same time, Sam, who’s building a position beyond which we won’t move.”

In a book chapter entitled “Identity and Democratic Institutions,” Pildes took a comparative approach, looking at how countries with sharply divided heterogeneous societies—like India, South Africa and Iraq—deal with designing democratic institutions. One common mistake: Designers assume that the conflicts among competing groups are fixed and unchanging, so they set up government in a way that—surprise, surprise—only entrenches those identities. Yet countries and societies are fluid, and the best systems design for that. An obvious example: the United States and federalism, which accommodates regional preferences and changes. In Iraq, designers at least set up a rotating presidency among the three major groups as an interim measure to navigate tension. Interim power-sharing was also done in South Africa after apartheid.

Similar issues of fragile democracies were in the Constitutional Democracies colloquium run by Issacharoff, Pildes and Pasquino. Roughly 30 students heard presentations from speakers including justices from courts in Germany, France and Israel. “It was an important event,” says Pasquino, exposing students to views from justices around the world. He notes that Europe doesn’t have many academics like Issacharoff and Pildes who specialize in election law. The reason, he says, is that in countries like France and Italy, only one national law governs the electoral process—unlike the 50 different laws in the United States. But democratic design is an important topic these days in Italy, which is debating switching from a proportional system of electing representatives to an American-style majoritarian one. “A coalitional government is a huge problem,” saysPasquino, who favors the switch. “It’s indecisive, and if you have 20 parties, it’s hard to attribute responsibility.”

Elections Abroad

In U.S. domestic politics, elections always appear to be a good thing, the exercise of individual rights to influence how to run the nation. But this doesn’t necessarily translate overseas, especially when ill-prepared countries with new democracies rush to hold elections. Issacharoff criticizes American foreign policy in recent years as “hold the goddamn elections someplace at some time and the outcome be damned.” That policy has only exacerbated tensions in places like Iraq, Palestine and Kazakhstan. A presidential election, he says, needs to be preceded by such things as functioning parliamentary institutions, some judicial counterweight and human rights monitors. Otherwise, “an election can be a referendum on who’s going to use state power to suppress everyone else, and that’s not a democracy,” Issacharoff says.

In a Washington Post opinion piece published in 2005, Issacharoff argued that what defines a democracy is not the first election but the second. Pildes thinks the rush stems from the “naïve, romanticized” image of democracy held by many people—to wit, all will be fine if we can get citizens just to speak their minds and vote their preferences.

Trying to export Western-style democracy generally is fraught with dangers. Walter E. Meyer Professor of Law Stephen Holmes, who has written extensively and consulted on emerging democracies in Eastern Europe, also has little time for people who “pretend to be experts” and go around the world selling their services as constitutional or electoral engineers. “You can more easily unplug an appliance in New York and plug it in in Moscow,” Holmes says, “than you can unplug our due process system and put it in Moscow.” He recalls how, in the early 1990s, some American lawyers grew concerned that Albania was removing judges without cause. They went there and had the law rewritten to prevent that. So the Albanians starting putting judges in jail instead.

What’s critical is a thorough understanding of the informal networks that determine whether a country functions well or not. In Iraq, for example, Holmes says the United States lost three to four years insisting it would negotiate only with elected officials rather than tribal leaders. “This was a case of trying to export democracy, which blinded us to the elementary building blocks of a negotiated settlement in Iraq,” he says. Similarly, he ponders whether having an election today in Pakistan would make their handling of nuclear weapons more or less safe. “You can’t assume you know the answer,” Holmes said.

To say that the only legitimate leaders are those elected “shows a zero understanding of world history,” Holmes contends. “Most leaders throughout history have not been elected, and they have been as effective or ineffective as elected ones.”

Waldron, on the other hand, is not so quick to question elections. Of course, he says, it makes little sense to have elections without traditions like mutual tolerance and a culture of deliberation. But he argues that peoples’ urge to participate in elections is strong—witness Iraq or South Africa—and should be respected. “What I definitely reject is the view that the electoral dimension of democracy is a sham, or just icing on the cake,” Waldron asserts.

Such rigorous discussion underscores how important Law of Democracy is and will continue to be in domestic and world politics. Change, whether it be in the form of a new democracy created or an established democracy like the United States facing the real possibility of electing its first black president, seems an integral element of our times and for the foreseeable future. And you can bet that Samuel Issacharoff and Richard Pildes will continue to insert their idiosyncratic views into the global debate.

—Larry Reibstein is a New York journalist who has previously written about law and philosophy for the magazine.

—Editor’s note: Since this article was published in September 2008, Adam Cox has joined the NYU Law faculty.

—