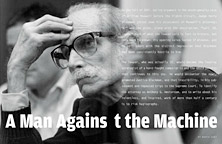

A Man Against the Machine

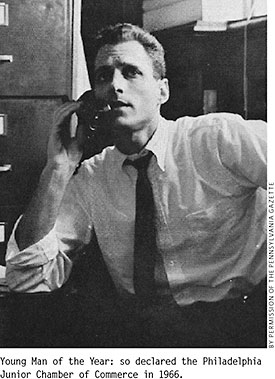

Printer Friendly VersionThe lawyer, who was actually 32, would become the leading strategist of a hard-fought campaign to end the death penalty that continues to this day. He would encounter the newly-promoted Justice Blackmun, and that irascibility, in his subsequent and repeated trips to the Supreme Court. To identify the attorney as Anthony G. Amsterdam, and to write about his relentless, and inspired, work of more than half a century is to risk hagiography.

Lawyers who have worked with Anthony Amsterdam cast about for the perfect superlative when they talk about him: His is “the most extraordinary legal mind of anyone I know”; he has a “visionary, imaginative sense of the edges of the possible”; his use of language is “so perfect and so powerful and so utterly logical”; he could “take a pile of coal dust and make a diamond out of it”; indeed, “God broke the mold when he created Tony.”

And yet, these acolytes of Amsterdam’s are among the most respected members of a profession inclined to contrarianism, not reverence; in order, they include George Kendall, a senior counsel at Holland & Knight who headed the capital defense section of the N.A.A.C.P. Legal and Educational Defense Fund (LDF); Sylvia Law, the Elizabeth K. Dollard Professor of Law, Medicine and Psychiatry at the New York University School of Law; Tim Ford, a respected civil rights attorney; David Kendall, a lawyer who is no relation to George, though he also headed the capital defense section, and is best known for representing President Bill Clinton during the Monica Lewinsky debacle; and Seth Waxman, a former solicitor general who continues to argue regularly before the Supreme Court.

Even the Supreme Court justices, who would prove Amsterdam’s toughest audience, did not know quite what to make of the lawyer whose intellect was matched only by the intensity of his opposition to the death penalty. In 1976, after a particularly combative session in which Amsterdam tried, and failed, to persuade the Court to maintain its effective ban on the death penalty, one justice reportedly grumbled, “Now I know what it’s like to hear Jesus Christ.”

Amsterdam still walked among mortals in 1966. When Orval Faubus was wrapping up his tenure as governor of Arkansas, he signed six death warrants and rushed off to California to attend a conference. One bore the name of William Maxwell, a young black man convicted four years earlier of raping a 35-year-old white woman and sentenced to death. Maxwell had appealed to the Arkansas Supreme Court, arguing that jurors in the state had applied the death penalty in a discriminatory manner. He lost. He had submitted a petition for a writ of habeas corpus, a request that the judge free him because his conviction was unconstitutional, in federal court. It was denied. He had appealed to the Supreme Court. It refused to hear his case. Maxwell was running out of options.

While Faubus was flying west, Amsterdam, then a professor at the University of Pennsylvania Law School, was called out of an LDF workshop in New York City. Within hours—as Michael Meltsner, Amsterdam’s colleague at LDF, recounts in his compelling 1973 book, Cruel and Unusual: The Supreme Court and Capital Punishment— Amsterdam was dictating a second petition for habeas relief by phone to the secretary of one of Maxwell’s lawyers.

Filed in court the next day, Maxwell’s petition marshaled some of Amsterdam’s most persuasive arguments against the death penalty. The death penalty, the petition contended, was unconstitutional on a number of procedural grounds: Jurors were given no guidance about how to reach a decision, leading to arbitrary results; the single-verdict trial, in which the jurors had decided Maxwell’s guilt and sentence simultaneously, denied them the opportunity to weigh mitigating factors; and lastly, and most controversially, the petition raised Maxwell’s claim of bias once more, grounding it in a new study that LDF had commissioned by a respected criminologist, Marvin Wolfgang. In the period from 1945 to 1965, black defendants who raped white women in Arkansas stood a 50 percent chance of being sentenced to death if they were convicted, compared to a 14 percent chance for white offenders.

The petition was denied, but Amsterdam and LDF continued to exploit every possible legal remedy, appealing to the Eighth Circuit without success and then seeking a stay of execution from the Supreme Court. This time, the Court granted the relief, sending the case back to the appellate court, which didn’t exactly welcome it.

Blackmun, who had received a math degree from Harvard, was not persuaded by Wolfgang’s research. He found the survey sample too small to offer convincing proof of discrimination. And even if the study could prove past discrimination in Arkansas, it did not include data from the county where Maxwell was convicted or interviews with the specific jurors in his case. As Blackmun wrote for the three-judge panel, “We are not yet ready to condemn and upset the result reached in every case of a negro rape defendant in the State of Arkansas on the basis of broad theories of social and statistical injustice.”

Blackmun’s opinion suggested annoyance with Amsterdam. In the course of argument, Amsterdam had been asked whether his analysis meant that a black man could not be put to death under the Constitution for raping a white woman. Amsterdam replied in the affirmative, according to Blackmun. The judge wanted to know if the same logic would hold true for a white man convicted of rape—a fair question on its face but one that ignored the reality that nearly all the defendants executed for rape in the South were black. Amsterdam conceded that his argument did not apply to a white defendant. “When counsel was asked whether this would not be discriminatory,” Blackmun wrote, “the reply was that once the negro situation was remedied, the white situation ‘would take care of itself.’” Blackmun didn’t appreciate the sally.

Amsterdam refused to whitewash what he saw as the discriminatory application of the death penalty. Sitting in his fifth-floor office at Furman Hall recently, he explained why he got involved in death cases. “It wasn’t some sort of ideological opposition to the death penalty,” he said. “It was all about race initially.” In Maxwell’s time, Amsterdam said, local white lawyers could not represent blacks charged with high-visibility crimes against whites without fear of retaliation. LDF, and its roster of “carpetbagger” lawyers, as Amsterdam put it, stepped forward.

But Maxwell’s case brought home to Amsterdam and his colleagues at LDF that they could no longer ignore the pressing needs of all death-penalty clients—whatever their race and whether they had lawyers or not. Amsterdam was Maxwell’s lawyer, but there were four other men without lawyers whom the governor of Arkansas had consigned to death as well. “We said, ‘What the hell! Are we going to let these guys die?’” Amsterdam said. “It was like somebody was bleeding in the gutter when you’ve got a tourniquet. Then, we were in the execution-stopping business.”

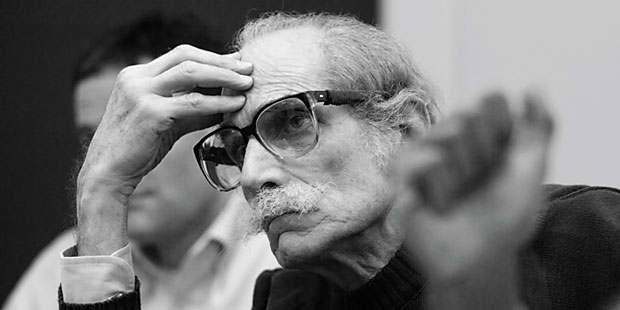

It takes some doing to imagine a suave 32-year-old hidden in the layers of Amsterdam’s past. When we met the first time, he wore a red-and-green flannel shirt, olive-green corduroys, and a thin knit tie that approximated the color of his pants. The shirt hung from his frame, so lean that the only matters of substance about him seemed to be a bushy moustache and sunken gray eyes that stared out of the kind of oversized glasses only a septuagenarian would risk. Amsterdam’s hearing has been poor since birth; he wears a hearing aid in his right ear, which picks up sound from a black box that he positions on the table in front of him.

But it is his eyes that draw attention—eyes that look, as one colleague of Amsterdam’s put it, like they’ve never slept. All-nighters became routine for Amsterdam in the mid-1960s, around the time when he and a band of lawyers at LDF began marshalling the tools they had in hand to save lives. Chugging down bottles of diet soda and chain-smoking thin cigars, Amsterdam forged the legal infrastructure that helped LDF to challenge just about every death penalty case across the country. He and the LDF lawyers created the “Last Aid Kit,” which included sample petitions for habeas corpus, applications for stays of executions, and legal briefs setting forth constitutional arguments against the death penalty; they distributed the kit to capital defense lawyers across the country. With a boldness that is hard to grasp today, Amsterdam set out to change minds about the death penalty by creating a sense of emergency.

But it is his eyes that draw attention—eyes that look, as one colleague of Amsterdam’s put it, like they’ve never slept. All-nighters became routine for Amsterdam in the mid-1960s, around the time when he and a band of lawyers at LDF began marshalling the tools they had in hand to save lives. Chugging down bottles of diet soda and chain-smoking thin cigars, Amsterdam forged the legal infrastructure that helped LDF to challenge just about every death penalty case across the country. He and the LDF lawyers created the “Last Aid Kit,” which included sample petitions for habeas corpus, applications for stays of executions, and legal briefs setting forth constitutional arguments against the death penalty; they distributed the kit to capital defense lawyers across the country. With a boldness that is hard to grasp today, Amsterdam set out to change minds about the death penalty by creating a sense of emergency.

In some ways, LDF’s campaign against the death penalty tapped into the country’s mood. In the 1930s, an average of 167 executions was carried out yearly; by the early 1960s, the annual average had dropped to 48. Amsterdam and LDF resolved to bring those numbers to zero. “The legal acceptance and historical force of the death penalty were considered a given,” said Jack Himmelstein, who headed the capital defense section at LDF during that time. “It was the power of Tony’s mind and heart that said, ‘That doesn’t have to be the case.’” By the early ’70s, that refusal to accept the death penalty as a given had translated into the continued survival of about 700 individuals on death row. An effective, if not official, moratorium was in place; the last legal execution had taken place on June 2, 1967, and few judges wanted to be the first to begin clearing the row. Amsterdam’s legal arguments against the death penalty made their way up to the Supreme Court, which did its utmost to bat away the increasingly unavoidable question—was the death penalty still constitutional in the United States?

By the end of 1971, the Court seemed well on its way to answering “yes.” In 1971, with the freshly appointed Justice Blackmun on the bench, the Court rejected two of Amsterdam’s most powerful arguments against the death penalty—that the absence of standards guiding a jury’s decision to sentence a defendant to death was unconstitutional, and that a defendant was denied his right to a fair trial if his guilt and sentence were decided by a jury at the same proceeding. Amsterdam had only one argument left in his quiver, and it was his longest shot: that the death penalty was cruel and unusual punishment.

How could Amsterdam convince the Court that a punishment which a decade ago had been “a given” had suddenly become cruel and unusual? As was his custom, he delivered his oral arguments in two of the four death-penalty cases before the Court without notes, setting out in Furman v. Georgia to neutralize what was likely to be the fallback position of the justices—that it was up to legislatures, not judges, to decide whether the death penalty should exist. The legislature could find a legitimate basis for boiling a criminal in oil, for example, but the Court might well find the punishment “unnecessarily cruel.” Forty-one states had death penalty statutes on their books, Amsterdam conceded, but the key question was: “What do they do with it?”

The penalty was “almost never” inflicted. One in a dozen juries at the most returned a sentence of death, according to statistics that LDF had compiled, and only a third to half of those defendants were actually executed. (Amsterdam was treading on dangerous ground here, because it was his own strategy at LDF that had contributed to declines in the number of defendants executed.) Then he built to his next point, that the rare sentence of death fell only on the “predominantly poor, black, personally ugly, and socially unacceptable”— those for whom “there simply is no pressure on the legislature” to take the penalty off the books. Amsterdam seemed to be having an effect on Justice Byron White, whom the LDF had anticipated would be squarely in favor of upholding the death penalty. Justice White rocked back and forth in his chair, and his face was ashen, according to Meltsner’s account in Cruel and Unusual. In The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court, Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong report that White later told his clerks that Amsterdam’s oral argument in Furman was possibly the best he’d ever heard.

In the summer of 1972, the Court announced its verdict in Furman, a decision that, at nearly 80,000 words including footnotes, remains among its longest. By a margin of 5-4, it found that the death penalty was “cruel and unusual punishment” in violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments. The justices could agree on little else, however. Each one of the nine justices penned his own opinion. Justices Potter Stewart and White offered the narrowest grounds, finding that the arbitrary application of the death penalty was unconstitutional. “These death sentences are cruel and unusual in the same way that being struck by lightning is cruel and unusual,” Justice Stewart wrote. While emphasizing that he did not find the death penalty “unconstitutional per se,” Justice White sided with the majority, finding that “the penalty is so infrequently imposed that the threat of execution is too attenuated to be of substantial service to criminal justice.”

Justice Blackmun, for his part, offered a dramatic dissent. “Cases such as these provide for me an excruciating agony of the spirit,” he wrote. “I yield to no one in the depth of my distaste, antipathy, and, indeed, abhorrence for the death penalty,… and of moral judgment exercised by finite minds.” He went on to conclude, however, that he was not a legislator and therefore could not allow his personal preference to guide his judicial decision.

Amsterdam was driving along a highway south of San Francisco when he heard the news on the radio. He pulled over, sat, and looked around him. “You represent people under sentence of death, you’re always walking around with a dozen, 50 lives on your shoulders,” he said. “The feeling of weight being lifted, knowing that these guys…you worry about each and every one separately.” For the first time in longer than he could remember, Amsterdam stopped, and didn’t feel guilty about standing still. Recalling the moment with his hands clasped behind his head and his eyes closed, he said, “I felt free for the first time in years. I thought, ‘That job is done. Those guys are gonna live.’”

Ask Amsterdam about himself, and he seems uncomfortable and slightly bored by the topic. He answers some questions out of a deep sense of courtesy, but in the universe of potential conversation—about art, basketball, law, anything, please!, but himself—he’d rather not pursue this line of questioning. If Amsterdam had his way, his biography would contain a single line: In his youth, the lawyer occasionally played pick-up basketball with the legendary Wilt Chamberlain.

Amsterdam grew up in a middle-class neighborhood in West Philadelphia. His father, descended from a line of rabbis, served as a military lawyer in Luxembourg during World War II; after returning home, he became a corporate executive. His mother did a range of volunteer work.

Judaism provided the backdrop of his childhood, but it never entered the foreground. His parents weren’t observant, which may explain why they gave their son a name—“Tony”—that seemed to align him with the Italian-Americans who, along with Jews and African-Americans, comprised the community. After attending a predominantly Jewish grade school, Amsterdam enrolled in a junior high school that reflected its location at the intersection of the three ethnic communities. “I tended to run with a crowd that had all three groups in it,” Amsterdam recalled. “Like most kids of that age, we had our games.” Box ball, played in a square laid out in the school’s courtyard, was a favorite of his but there were also basketball, football and tennis.

The fun came to an abrupt halt, however, when Amsterdam turned 12 and was hit with bulbar polio. Though spared the paralysis of the limbs that can accompany the often fatal disease, he spent days in an iron lung and was quarantined for a longer period of time that remains a blur for him now. Amsterdam’s highly retentive memory fails him when he trains it on his youth, a quirk that is either a convenience or a symptom of his lack of self-interest. But Amsterdam does remember the upside of being bed-ridden: He was elected to become box ball captain in absentia and returned in time for the end of the season “mightily inspired to play better.”

At college—Haverford—French literature became the new box ball. Amsterdam majored in comparative literature, and consumed 17th-century French poetry with an appetite he would later bring to Supreme Court opinions. Schoolwork for its own sake didn’t excite Amsterdam, but college offered new ways of thinking that were exhilarating. “College opened doors to a lot of things I hadn’t thought about,” Amsterdam said. “I pushed myself very hard, but not to study in the sense of folks who are trying to accomplish something.” If he didn’t like a course, he didn’t spend much time on it. He read the assigned pages, and “got done what needed to be done.” For Amsterdam, that translated into summa cum laude at both Haverford and the University of Pennsylvania Law School.

Amsterdam fell into law school without any firm intent. While at college, he had participated in some early civil rights sit-ins in Delaware, and the law seemed to be connected to that. Still, Amsterdam spent much of his time in law school auditing lectures on art history at Bryn Mawr College. His enthusiasm for art stemmed from a period in high school when he had worked at a private museum. Between and sometimes during classes, he took long nature walks, painted water colors, read French poems and wrote some of his own, though mostly in English. Amsterdam also managed to keep up his duties as editor-in-chief of the law review, but two months before graduation, he hadn’t even begun the mandatory paper. He dashed it off: The result, the influential “Void-for-Vagueness Doctrine in the Supreme Court,” helped reshape First Amendment law. His later work, “Perspectives on the Fourth Amendment,” is ranked among the most-cited law review articles of all time.

Still, in 1960, the law’s hold on Amsterdam seemed weak, too weak to repel the pull of those art galleries. Fortunately for the bar, one of his law professors recommended him to Justice Felix Frankfurter, and the new graduate ended up clerking for the justice. It was during that year, when Amsterdam worked mainly on criminal cases, that he began to see the law’s potential. Those early sit-ins in Delaware took on new meaning as he witnessed the interplay of civil rights and criminal law. Mass demonstration had become an integral tool of the civil rights movement, and Amsterdam resented that the criminal process was being used to try to repress Dr. Martin Luther King—and hundreds of other activists.

Long after his official obligations as a clerk ended, Amsterdam continued working for the ailing justice, helping Frankfurter with his speeches and memoirs, which were never published. Frankfurter put him in touch with the U.S. Attorney of the District of Columbia; Amsterdam joined the office, and set to deepening his understanding of criminal law.

The results of his study were impressive. Anecdotes about Amsterdam’s powerful memory and unique intellect abound, but one incident in 1961 has captured the imagination of those who know him best. During his time as a government prosecutor, Amsterdam was handling an appeal that raised the question whether a defense psychiatrist could testify that the defendant had a mental disease within the meaning of the insanity defense. Arguing before a three-judge panel, Amsterdam drew an analogy to life insurance, arguing that a medical expert witness would not be permitted to testify that an insurance claimant had a “total and permanent disability” within the meaning of his insurance contract. Shaking his head, the judge pressed Amsterdam, who cited an old Supreme Court case by volume and page in support of his point. The judge called over an assistant and asked him to fetch the volume. After flipping to the page number Amsterdam had offered, the judge hastened to report that the case wasn’t there. Amsterdam replied that the volume must be mis-bound. Not willing to give up so easily, the judge probed further, and discovered that 210 U.S. was bound in the cover of 211 U.S. When the correct volume was located, he found the case on the cited page.

The government would inevitably lose Amsterdam, who is more comfortable upending, rather than upholding, the establishment. After a year and a half as a prosecutor, Amsterdam joined the faculty at the University of Pennsylvania Law School, and began splitting his time between teaching and consulting on civil rights cases across the country. Time took on an altered quality; there was no longer enough of it and something—a lecture to prepare, a brief to edit, a student to mentor—was always pulling at him. Even today, he can’t quite control his time, though he tries by breaking it into blocks and dispensing those blocks with extreme generosity. When Seth Waxman, for example, was asked to argue Roper v. Simmons, which persuaded the Court to abolish the juvenile death penalty two years ago, he immediately turned to Amsterdam. He received an email from the professor within minutes, saying: “‘I have to teach a course in seven minutes until 6:30, and then I’m editing a brief, but I could be available from 11:10-11:30 p.m. or from 4:30-4:50 a.m.’” Waxman recalled thinking, “I’m unworthy. There I was asking for help on short notice and there he was, almost apologetic in freely offering time at the very edges of the night.”

Amsterdam worked 20-hour days in the ’60s. David Kendall’s theory was that there were two Amsterdams. The “Tony” he worked with—the one who chain-smoked cigars and was sometimes accompanied by his two dogs, Brandeis and Holmes—would switch roles every 12 hours with a clone who caught up on sleep. (The personalities of the dogs reflected their judicial namesakes, Amsterdam said: “Holmes was a real patrician, a large dog who condescended to spend time with us. Brandeis had a concerned, thoughtful quality.” The dogs, who died of old age, were succeeded by Mandy and Pru, short for Mandamus and Prohibition, two kinds of judicial prerogative writs.)

In 1965, Amsterdam helped oversee LDF’s project to collect data on racial bias in about a dozen Southern states for the Wolfgang study he referred to in Maxwell. That same year, he cowrote an ACLU amicus brief for Miranda v. Arizona that described police procedures during interrogations; the brief cited police manuals at length that exhorted the interrogator to “dominate his subject and overwhelm him with his inexorable will to obtain the truth.” Chief Justice Earl Warren lifted that passage, and many others, wholesale from the ACLU brief in his decision revolutionizing police practice. In 1967, Amsterdam cowrote an amicus brief for LDF, this one on the police’s stop-and-frisk tactics. In 1969, he helped in the appeals of the Black Panther Bobby Seale and the civil rights demonstrators known as the Chicago Seven. Around the same time, he began working on a landmark case of journalistic privilege, defending Earl Caldwell of the New York Times from prosecution when he refused to turn his notes on the Black Panthers over to the F.B.I.By 1972, when Amsterdam argued Furman, he had filed dozens of briefs with the Court, once conducting oral arguments in three unrelated cases in the space of a week. Meanwhile, he was receiving letters from death-penalty prisoners seeking help.

Something had to give, and Amsterdam had too much integrity to short-change his clients. “Once you assume the responsibilities of attorney to client, you do what has to be done. You leave no stone unturned,” he said. “No French poem in the world demands that of anybody.” If Amsterdam has a weakness, it may be that he is unable to resist the needs of others. Norman Redlich, the former dean of NYU School of Law who succeeded in hiring Amsterdam from Stanford in 1981, recalled when he was hospitalized for surgery on an optic nerve a decade later and received a flurry of notes from faculty members offering to help if they could. Amsterdam’s note was different. “He said, ‘These are the things I can do: I can go to the cheese store, walk the dog,’” Redlich said. There were at least 10 items on the list, and Amsterdam asked the dean to check the ones he’d like, which he did.

What Amsterdam gives to his clients and everyone else is easy to chart; his losses are harder to trace. When a novel went unread or a painting didn’t materialize or a poem went unwritten, did Amsterdam feel regret? He won’t say, except to insist that his work isn’t a sacrifice.

As generous as Amsterdam is of himself, when faced with pesky questions from this reporter, he zealously defended a private space for himself and his loved ones. He would say nothing about his family except that his wife of nearly 40 years, Lois Sheinfeld, shares his commitment to causes. Hers was poverty law when they met; it is now the environment; she writes and lectures on organic gardening and other environment-saving measures.

Earl Caldwell caught a rare glimpse of Amsterdam’s private side in 1969. He recalled catching the recently married Amsterdam and his wife at their home in Los Altos, California, after midnight. Caldwell, desperately in need of a lawyer, had driven there with a coalition of black journalists. “Frankly, we didn’t have anyone else,” Caldwell said. “We were reluctant, wondering: ‘How do we know we can trust him? Who is this white guy?’” Sheinfeld made coffee and chatted with the journalists to put them at ease. Amsterdam didn’t waste time: He dove right in, telling Caldwell that he didn’t have to turn his notes on the Black Panthers over to the FBI. “I’ve been studying the case and mind you, they can’t make you do it. You have a legal right to refuse,” Amsterdam said. From then on, Caldwell knew he had his lawyer. “He was a person I always felt looked at you and all he saw was a human being,” he said.

In Furman, Justices Stewart and White made clear that they weren’t abolishing the death penalty outright. States could respond with new legislation crafted to meet the Court’s insistence on rational, uniform standards in applying the death penalty. With a speed that surprised even Amsterdam, who knew better than to celebrate for long, 35 state legislatures across the country raced to comply.

Four years after Furman, in 1976, Amsterdam was back before the Court to argue that the newly enacted statutes did not meet the constitutional bar. The Court had chosen to hear five capital cases that represented a sampling of the new laws, and Amsterdam argued three of them over two days. He began by giving an overview of all 35 statutes, organizing them into four categories, and adding that the states had come up with “elaborate winnowing processes” and “an array of outlets” to avoid the use of the death penalty. Amsterdam argued that the reforms that had been made in response to Furman were largely cosmetic, leading to the same arbitrary outcomes that had troubled Justices Stewart and White so deeply. Justice Stewart questioned whether Amsterdam’s focus on the exercise of discretion throughout the judicial system “prove[d] too much.” Amsterdam did not budge from his stance, insisting, “Our argument is essentially that death is different. If you don’t accept the view that for constitutional purposes death is different, we lose this case.”

In July of 1976, in the cases that are known collectively as Gregg v. Georgia, the Court found that death wasn’t so different after all. It struck down mandatory death-penalty laws like one in North Carolina, but upheld statutes like one in Georgia, which compelled juries to weigh aggravating and mitigating factors. Judge Thurgood Marshall read a pained dissent in Court, and suffered a mild heart attack later that evening.

In The Supreme Court and Legal Change, Lee Epstein and Joseph Koblyka fault Amsterdam for his absolutist position, accusing the lawyer and LDF of misreading the doctrinal glue that held the Furman majority together. Justices Stewart and White were concerned with process, and not substantive arguments based on the particularity of the death penalty. If Amsterdam had pursued a multilayered strategy, rather than boxing himself into an allor- nothing approach, the outcome of the case might have been different. Edward Lazarus, a former clerk to Justice Blackmun, echoes that criticism in Closed Chambers: The Rise, Fall and Future of the Modern Supreme Court, reporting that Amsterdam’s “total immersion in the abolitionist cause” had “rendered him tone deaf to the changing tune of the country and the Court.” It is hard to imagine, however, what Amsterdam could have said to convince the justices to maintain their ban on capital punishment, after the country had roundly rejected that position. As Meltsner argues persuasively in The Making of a Civil Rights Attorney, Amsterdam chose the “deathis- different” approach because he had to find a way to attack the post-Furman statutes without indicting the discretionary decisionmaking that lies at the heart of the criminal justice system.

Amsterdam was surprised by the Court’s decision, not so much because it had reinstated the death penalty, but because it had backed away so readily from the concerns it had raised in Furman. “We really thought the Court would be more resistant than it was to evasions of the rules it laid down in Furman,” he said. “We were disappointed in precisely the proportion to our naïvete. Some days, you let yourself hope more than you should.”

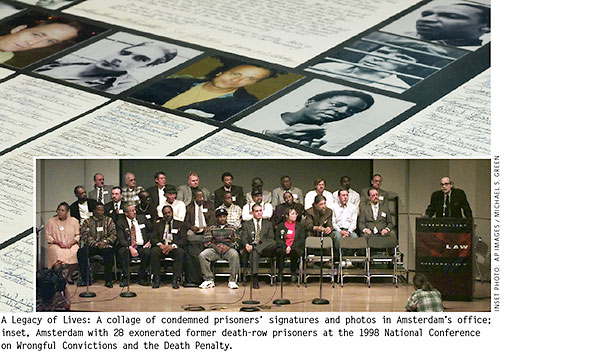

When I visited Amsterdam in January, a giant framed collage was packed away in his office. Presented at a 1990 LDF tribute to Amsterdam, it includes 52 photos and about 350 signatures of death-row prisoners through the decades and from across the nation. In one picture, a handsome dark-haired man with a streak of white hair running along the top of his head smiles at the camera. His name is John Spenkellink.

In 1979, Spenkellink became the first person executed against his will since the moratorium began in 1967. In the wake of Gregg, the newly elected Florida governor, Bob Graham, was determined to prove that, though he was a Democrat, he had the guts to carry out an execution. Spenkellink was not an obvious candidate for death. A convicted armed robber who had escaped from a prison in California, Spenkellink picked up a hitchhiker, a career felon 20 years his senior, in the Midwest. As Spenkellink told it, he was forced to perform sexual acts on the older man. He said he planned to abandon the man at a Tallahassee motel, but returned to the room and a fight ensued. While not denying he shot the man twice, Spenkellink maintained that he’d done so in self-defense.

“Our thought was that Florida chose him because he looked like such an ideal candidate from the state’s viewpoint. He wasn’t from Florida, was white, an escapee, and it was a relatively simple case,” David Kendall, Spenkellink’s primary attorney, said. “Otherwise, we couldn’t explain the decision.” Spenkellink had been offered a plea of second-degree murder, and turned it down. “The killing—if murder can ever be mitigated—was mitigated,” Kendall added. Kendall felt cautiously optimistic going into the clemency hearing; nearly everyone who knew Spenkellink then, including the prison warden, thought Spenkellink was a reformed man. Unfortunately, Kendall didn’t factor into the equation that Governor Graham couldn’t stand the sight of blood. After seeing photos of the crime at the hearing, according to David von Drehle in Among the Lowest of the Dead: The Culture of Capital Punishment, the governor left the room to throw up.

Spenkellink was the first of 17—17, and counting—men Amsterdam got to know well, and care about, who ended up dead. “After John’s death, I became much more vividly aware of the fact that this was a feature of our existence,” Amsterdam said. “You can’t be a capital defense lawyer without this.”

The realization changed Amsterdam. “In my heart of hearts, I couldn’t face the reality that things could go as wrong as they went and there was no correction, no remedy, no court would listen,” he said. That things can go so wrong is a constant reminder—not to hope, not to take anything for granted, not to stop. “You feel guilty about every one, simply because there has never been enough time in the day, you have never had enough skill,” Amsterdam said. “Hard as you try, you’ve got to admit that, life being what it is, maybe you could have tried harder.”

In 1981, eager to move to New York City and impressed by then-Dean Redlich’s commitment to clinical practice, Amsterdam arrived at NYU from Stanford Law School, where he had been teaching since 1969. In his first lecture, entitled “Saving the Law from [then-Attorney General] William French Smith…,” he laid out a new strategy for civil rights activists: In light of the Reagan-era conservative judiciary, they should downplay the significance of a case or create a factually messy record to discourage the Supreme Court from granting cert. In this manner, the Warren Court precedents might survive until a more liberal court was constituted.

“The present Supreme Court lineup is one which we superannuated football fans like to think of as two horsemen and seven mules,” the professor said, praising Justices William Brennan and Thurgood Marshall for “dissenting in virtually isolated splendor.” If public-interest lawyers were unfortunate enough to find themselves before the Court, however, they should make progressive arguments. “If you don’t raise these issues, you will not get the atrocious opinions which Justice [William] Rehnquist is capable of writing—and which, I firmly believe, we will one day have a judiciary fit to disavow.”

Amsterdam’s lecture wasn’t revolutionary, and no doubt he had communicated similar ideas at Stanford, but there was a key difference: It was delivered in Greenberg Lounge, which, it turns out, had a direct line to the New York Times in the reporter David Margolick, Amsterdam’s former student at Stanford. It was an indication of Amsterdam’s legendary status that the Times ran a sidebar with his comments, as if, Margolick recalled, they were “quotations from Chairman Mao.”

The lecture reflected the straight-shooting style of Amsterdam the professor, but it was a rare misstep for Amsterdam the lawyer, who continued to appear before those same seven mules on a regular basis. Asked if he regretted his comment, Amsterdam replied, “I regret almost everything I’ve ever said that was not absolutely necessary to say, and even some of the few things that were necessary. The seven mules is high on a very long list.”

In 1983, two years after his lecture at NYU, Amsterdam stopped arguing cases before theSupreme Court. The reasons for his unorthodox decision were complex. First, and of least importance, was his poor hearing. To compensate for it, Amsterdam uses a hearing aid and zooms that intense focus of his on a speaker to read lips. Still, in 1972, the problem was exacerbated by Chief Justice Warren Burger’s decision to shift from a straight to a curved bench. “Nine justices in a curved amphitheater does present a complicated problem,” Amsterdam said. “You don’t want to be blindsided.” On a number of occasions, even as early as Gregg, Amsterdam asked a justice to repeat a question. Lawyers with perfect hearing do the same, either because they miss a question or because they’re stalling for time. But in his final argument in 1983, Amsterdam unintentionally talked over a justice, who he hadn’t realized was posing a question over to the side. The vulnerability was slight, and few observers noticed it, but Amsterdam did.

Amsterdam had bigger problems on his hands, however. In 1976, after turning back from Furman, many of the justices wanted to put the debate over capital punishment behind them. But there was Amsterdam, year after year, scrupulously challenging each aspect of the system that put a man to death. The Court, and especially Justice Blackmun, didn’t need the constant reminder of what a procedural mess the death penalty was fast becoming. Amsterdam’s high-profile opposition to most of the judges now sitting in front of him, along with that unfortunate mule comment, didn’t help his popularity. “Having been a visible opponent of the confirmation of more than a majority of the Court and having written some very critical stuff about the Court’s opinions,” Amsterdam told me, explaining his continued refusal to argue orally, “I had a concern that some of that might rub off on a client.”

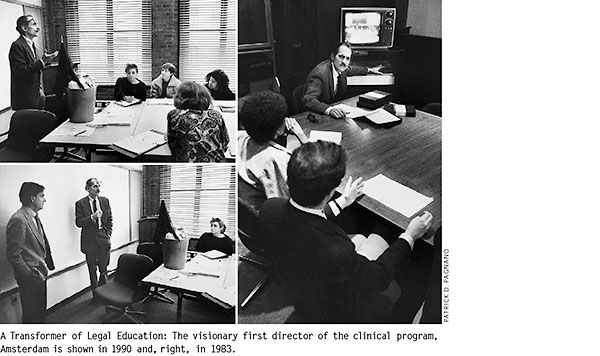

Staying off the podium also allows Amsterdam to have a broader influence. To play first chair in any one case takes a singularity of focus and time that Amsterdam can otherwise devote to teaching— in the most catholic sense of the word. Amsterdam is committed to helping everyone in his midst, whether they are officially his students or not, to become better lawyers. In 1967, he cowrote a trial manual about litigation that offered lawyers a systemic treatise on the nuts and bolts of how to try a case. In the ’80s, he brought that pragmatic, real-world sensibility to the NYU School of Law and reshaped legal teaching as the director of clinical education. Amsterdam initially taught a consumer protection clinic, but he had bigger ambitions. He wanted to create at NYU a full-fledged three-year-long program in which fieldwork clinics would represent the capstone of a progression of learning. “My image of a clinical program included pieces of varying sizes—clinics that were one semester and one year long, heavier and lighter—to enable students to have a smorgasbord set of choices,” Amsterdam explained. “Students could have as much or as little clinical education as they wanted.” To achieve his goal, Amsterdam developed a comprehensive course on “lawyering” that is now required of all first-year students and has been widely acclaimed. With those tools, students can graduate to simulation courses that follow a single case from start to finish and to full-blown clinics that involve fieldwork in actual cases.

Amsterdam no longer teaches the lawyering course, but he now coteaches the Lawyering Theory Colloquium, a course for 2Ls and 3Ls that brings an interdisciplinary approach to analyzing the law. The insights he gained from that class led to Minding the Law, which he co-wrote with the psychologist Jerome Bruner in 2000. In addition to the Colloquium, Amsterdam coteaches the two Capital Defender Clinics—the year-long New York clinic, which includes simulation and work on appellate cases, and the New York class sessions of the Alabama clinic, which sends students to the Southern state for fieldwork. (See “Bryan Stevenson’s Death- Defying Acts”.) The New York clinic grew out of a clinic that Amsterdam cofounded in 1996, a year after New York State reinstated the death penalty. When the district attorneys in New York City did not pursue death-penalty cases aggressively, Amsterdam regrouped, focusing the attention of his students on post-conviction work around the country.

When I visited the New York clinic last January, the students were acting as defense attorneys in a simulated case. Their client, based on a real defendant in California, was on trial for two homicides; he pleaded self-defense for the first murder and denied committing the second. Amsterdam welcomed the students back from winter recess, pausing when his aide delivered bottles of soda and bags of candy. “Bravo,” he said. “We’ll start over, properly equipped.”

As Hershey’s Kisses and Twix bars made their way around the table, Amsterdam sat back, crossed his arms behind his head, and began discussing strategies for managing the interplay between the guilt and penalty phases of a capital case. He asked, “What do you think is the price we pay if we take the position that our client didn’t do it at all?” A third-year student suggested that if the defense failed, the attorney would lose credibility with the jurors, which might harm the client’s chance at a sentence less than death. “Can we zero in on what it is the jury would be holding against us?” Amsterdam pressed. “What accounts for the demise or diminution of credibility?”

Amsterdam’s version of the Socratic method, not surprisingly, values humaneness over humiliation. He challenges his students, but is firmly on their side. When a question was met by silence, as the nine students looked awkwardly at one another, the professor responded, “Come on. If somebody goes over the hill, the others will follow.” Deborah Fins, who coteaches the class, chimed in: “Step in a toe. One toe and we’ll get you the rest of the way.”

The rest of the way can carry students to the Supreme Court. Over the years, Amsterdam’s students have worked on a host of high-profile appellate cases, including two of the most important “death-row cleaning cases,” as Amsterdam put it, that the Supreme Court has heard: Atkins v. Virginia, which abolished capital punishment for mentally retarded defendants in 2002, and Roper v. Simmons, the case Waxman argued that ended the penalty for juveniles in 2005. Amsterdam tries to involve his students in all aspects of cases: The students collaborate with Amsterdam and cocounsel on developing a litigation strategy; they conduct research and help to frame the issues to be argued, and draft pleadings, motions, petitions for review, and briefs.

The students also participate in the moot courts that Amsterdam hosts at the Law School for lawyers arguing death-penalty cases around the country. Last January, for example, five lawyers flew from Texas and Massachusetts to the sixth-floor conference room of Furman Hall to moot three cases about the Lone Star State’s mitigation practices. Two clinic students who had prepared questions for Amsterdam sat in on the session. “Some of the questions that he throws out at the moot are questions that we came up with together,” one of the students, Sungso Lee ’07, said. “Being in this clinic, I have to think more freely about the law and how it should be applied.” During the moot, the lawyers seemed to listen most attentively to Amsterdam, who acted as one of the six “judges” and expressed optimism that the current conservative Court would find in the capital defendants’ favor. (His instincts were proven right last April.) During a break, one of the lead lawyers came up to Amsterdam and asked, “Do you mind if I send you what will be my three-minute intro?” The professor responded, “Yeah, sure.”

Those requests come along frequently, and Amsterdam’s answer is always the same. His “edits” have become a source of gratitude, and some amusement, among his colleagues. In the days before computers, he used a bright red magic marker and his edits resembled a strange calligraphy, with carets marking new passages complete with full citations. James Liebman, a professor at Columbia Law School, sent his Supreme Court brief for a Florida deathpenalty case to Amsterdam, and received an edit that contained, among other things, an awkward line, which he then changed. When he sent it back to Amsterdam, the line was changed back. After a couple of back and forths, Amsterdam finally said: “I guess you’ve never written poetry. I’m making it awkward because I want the justices to stumble on that point in the brief. I want them to stop right there and think about it.” Liebman kept it, and Justice White adopted that very bit of analysis in his opinion giving relief to the defendant.

Amsterdam is described by one of his colleagues as a “special resource.” It’s tempting to begrudge that “resource” the time he devotes to teaching. Should Amsterdam be spending intensive, one-on-one time with Capital Defender clinic students when he could be consulting on even more civil rights cases? Arguably, though it’s hard to imagine how much more any one person could accomplish. More importantly, however, teaching is a rare unalloyed pleasure for Amsterdam. “He likes doing litigation with students. It’s a fresh eye and a fresh perspective,” Fins said. “For a lot of lawyers, especially as they grow older, their perspective on the world freezes. Tony gets really invigorated by his students.”

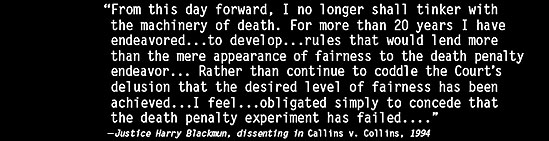

In 1994, in a routine denial of certiorari, Justice Blackmun appended a dissent that, along with Roe v. Wade, has become a defining moment in his legacy. “From this day forward, I no longer shall tinker with the machinery of death,” he wrote. “For more than 20 years I have endeavored—indeed, I have struggled— along with a majority of this Court to develop procedural and substantive rules that would lend more than the mere appearance of fairness to the death penalty endeavor.” He added that he found it impossible to reconcile Furman’s promise of consistent standards with its later guarantee in Lockett v. Ohio of individualized sentencing. Amsterdam had argued both cases.

It is hard not to read in that dissent vindication for Amsterdam, who withstood Blackmun’s hostility to persuade him of the very contradictions the justice identified in his dissent. It may also explain why the justice seemed so easily annoyed by Amsterdam. “I think I was a very convenient figure for him because I think he identified me with an idealistic part of himself that he felt it was his duty as a judge to severely repress,” Amsterdam said. Blackmun retired a few months after his famous dissent, choosing to withdraw from the mess that capital punishment had become and arguably always was.

Amsterdam stands firm, working to save lives and dismantle the system of capital punishment case by case. “When this country repudiates the death penalty, as it will, people will look back at him and say, he devised the campaign that led to this,” David Kendall said. If that happens, and those people know about the low-profile professor, perhaps they’ll come to the same realization that Blackmun seems to have reached: that Amsterdam had it right all along.

—Nadya Labi is a writer based in New York City.