Public Interest Yesterday and Today

NYU School of Law’s accomplishments in public interest law are marked at one end by the founding of the Root-Tilden Scholarship Program in the 1950s and on the other end by the past year’s notable developments, including the funding of summer public interest internships for all J.D. students.

Printer Friendly VersionTracing Our Roots

The Root-Tilden-Kern Scholarship Program Celebrates 50 Years of Inventive Legal Education

It was 1951. Dean Emeritus Arthur Vanderbilt had nurtured a vision for New York University School of Law during his tenure as dean, and was seeing it come alive. Vanderbilt had successfully moved the Law School, then known as the Law Center, from three floors of a factory building in Washington Square to a Georgian structure named Vanderbilt Hall. The dedication ceremony, held that September, was attended by “internationally famous jurists, lawyers, educators, and laymen,” and received press attention from the New York Times, Post, and Newsweek.

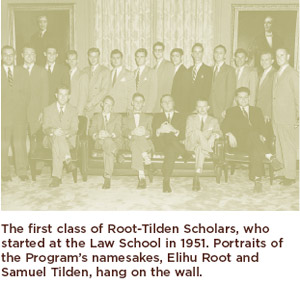

In the same month, “20 top-flight students, fresh from the campuses of as many American universities” arrived at NYU School of Law and graduated in 1954, the first of more than 800 Root-Tilden Scholars who have graduated to date.

In the same month, “20 top-flight students, fresh from the campuses of as many American universities” arrived at NYU School of Law and graduated in 1954, the first of more than 800 Root-Tilden Scholars who have graduated to date.

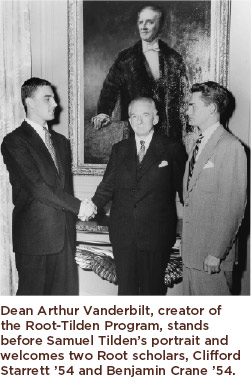

Vanderbilt, who was dean from 1943 to 1948 and then chief justice of New Jersey, conceived of the Root-Tilden Scholarship Program in the 1940s, setting into motion the transformation of the Law School from a neighborhood law school to a nationally and internationally esteemed institution. Vanderbilt was troubled that some of the best students and lawyers had become more concerned with making a living than they were with participating in American democracy. He feared that students were no longer receiving the proper encouragement and guidance to become “unselfish and competent public leaders,” and to serve as leaders of the bar.

In creating the Root-Tilden Scholarship Program, Vanderbilt put NYU School of Law on course to its top-tier level, and laid the groundwork for a model of public service legal education and scholarship that has influenced law schools nationwide. He named the Program for two alumni, Elihu Root and Samuel Tilden, who exemplified his ideal lawyer.

Elihu Root, who graduated in 1867, was a U.S. attorney in New York, a leading member of the American bar, secretary of war under President McKinley, and secretary of state under President Theodore Roosevelt. In 1912, he received the Nobel Prize for his contributions to international law. Samuel Tilden, a graduate of the class of 1841 and a renowned prosecutor, was a popular New York governor who ran for president in 1876 against Republican Rutherford B. Hayes. The results of this election were so close and hotly contested that a few news outlets even pronounced Tilden the winner in a Bush/Gore story of yore.

Interestingly, both Root and Tilden had played leading, and opposite, roles in the prosecution of the powerful New York City “Boss” Tweed in 1873, epitomizing the different forms public service can take. Tilden led the Citizens Committee of Seventy that combated the notorious Tweed Ring. Root, at 28, was a junior member of a distinguished defense team representing Tweed.

Program Architecture

The original structure of the Root-Tilden Program, which celebrates the 50th anniversary of the graduation of its first class in 2004, has largely remained intact, although it has evolved to fit contemporary needs and culture. Vanderbilt designed the Program as a multipronged effort to build the reputation of the Law School, while also resolving what he saw as the “major shortcomings” of legal and pre-legal education: inadequate instruction in procedure, judicial administration, and public law and an insufficient undergraduate education.

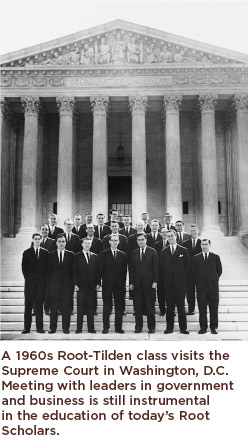

To enhance legal education, Vanderbilt’s Program required scholars to take special courses in the humanities, social sciences, history, and natural sciences. In the early decades, they were also required to live together and to share mealtimes, for lunch and dinner, five days a week. To instill Vanderbilt’s values of public service, scholars regularly met with leaders in government, industry, and finance, just as the scholars do today through events like the Monday Night Speakers Series.

To enhance legal education, Vanderbilt’s Program required scholars to take special courses in the humanities, social sciences, history, and natural sciences. In the early decades, they were also required to live together and to share mealtimes, for lunch and dinner, five days a week. To instill Vanderbilt’s values of public service, scholars regularly met with leaders in government, industry, and finance, just as the scholars do today through events like the Monday Night Speakers Series.

The Program was first funded by a $360,000 check from the Avalon Foundation. It was described as a five-year “experiment” in a lengthy letter from the foundation’s trustees that outlined the terms of their financial support.

“The whole purpose of this project is to attempt to determine whether it is possible to train promising young men so as to help attain again for the American bar the high position which it once held as the reservoir of altruistic and competent public leadership,” they wrote.

Twenty scholars were selected for the first class, two from each of the country’s then 10 judicial circuits. They were all, by requirement, unmarried men, under the age of 28, who each received $2100 a year to cover full tuition, books, and living expenses. Their success following graduation convinced the trustees at the Avalon Foundation that Vanderbilt’s Program had achievable goals, and they extended the Program with a gift of $875,000, which was matched by the Law Center Foundation and the University.

“The original idea was to bring in people who would have the highest respect for the laws of the country, and who would uphold them in the most ethical manner,” says Thomas Brome (’67), a Root alumnus. “These men would live together and dine together, forming a community of scholars who were infused with interests beyond the mechanical practice of law.”

Additionally, the Program’s promise of a debt-free legal education attracted students who might otherwise choose what were then more prestigious national schools.

“It was clear from my father’s comments that I would be crazy to choose Yale or Harvard when NYU offered what it did,” says David Washburn (’55), a Root-Tilden alumnus who had these three options. “We were a poor family from a small town in Vermont.”

Traditional Public Service

Like many of the Root alumni from the ’50s and ’60s, Washburn and Brome went on to work for prestigious firms in the private sector. Throughout their careers, both of them have been leaders in public service and also have given back to the Law School as substantial contributors, donating money and time.

Brome has been an instrumental force in bringing Roots together around the country for discussions about the Program’s financial issues and future framework, and to encourage active alumni support of the Program. An intern at the Legal Aid Society while a student at the Law School, Brome later served as Legal Aid’s board president while working as a partner at Cravath, Swaine & Moore. According to Professor Anthony Thompson, who served as faculty director of the Program for four years beginning in 1999, Brome is emblematic of Root alumni of his generation.

“The earliest generation was charged with the task of being successful in both the public and the private sector,” Thompson says.

Thompson notes that the definition of public service law has been through several iterations, shaped by social and economic changes. However, he believes that certain core values and a commitment to upholding the highest standards of the law are preserved, and regardless of the generation, Root Scholars all share an “incredibly strong allegiance” to the Program.

A Case in Point

Former New Jersey Supreme Court Justice Stewart Pollock (’57), for one, felt that it was his duty to go into public service if tapped for it, which he was — literally.

Pollock, who like Brome is a Law School trustee, worked in private practice for the better part of his early career, first for a firm that was a successor to Arthur Vanderbilt’s own firm, and then joining Clifford Starrett (’54), also a Root graduate, at Schenck, Price, Smith & King in Morristown, New Jersey.

“I was with Schenck, trying a case before our assignment judge who (after rendering a decision against me) resigned from the bench to run for governor,” says Pollock, referring to Judge Brendan Byrne.

Later that year, after Byrne won the New Jersey governor’s seat, Pollock went to file papers to appeal Byrne’s judgment and bumped into a friend who was soon to be sworn in as the New Jersey commissioner of human services. She invited Pollock to attend her swearing-in ceremony, and during the ceremony Pollock was tapped on the shoulder by a state trooper and invited to speak with Governor Byrne.

Later that year, after Byrne won the New Jersey governor’s seat, Pollock went to file papers to appeal Byrne’s judgment and bumped into a friend who was soon to be sworn in as the New Jersey commissioner of human services. She invited Pollock to attend her swearing-in ceremony, and during the ceremony Pollock was tapped on the shoulder by a state trooper and invited to speak with Governor Byrne.

“There was a huge energy shortage at this time due to the oil embargo, and the New Jersey legislature responded by making the Board of Public Utilities full time and bipartisan,” Pollock says. “The [Democratic] governor told me he needed a Republican lawyer, someone he could trust, to serve full time on this board.”

The salary for this position was about a third what Pollock was making in private practice, and his oldest child was about to start college with three siblings lined up behind her. Pollock recalls losing 15 pounds in a week over the anxiety this decision caused.

“What kept bugging me was that I had accepted a public interest scholarship, and one of Vanderbilt’s tenets was that you should accept public service when offered,” he says. After conferring with his wife, he committed to two years in the position. Two years later, Pollock returned to private practice, but it was only a short while before he was tapped again. When Byrne was reelected, he called on Pollock to serve as his chief counsel. Again, Pollock assumed that he would return to a private firm upon completing his term. Yet, two years later Byrne appointed him to the Supreme Court of New Jersey, and the Honorable Stewart Pollock served on the bench for the next 20 years.

“I saw Byrne recently and told him, ‘I wonder what would’ve happened if I won that case!’” says Pollock, laughing. “I wouldn’t have been down there filing those papers, but life is like that — serendipity rules.”

In reality, serendipity would have played an entirely different role if not for the impact of the Root-Tilden Scholarship. Pollock may not have set forth on the path that led to the New Jersey Supreme Court, and from there to his seat on the board at the Law School’s Institute of Judicial Administration and a teaching post in the Institute’s appellate judges program. His sense of public service inspired his law clerks to make a gift in his name to the Law School’s public interest programs after he retired from the Supreme Court in 1999 and reentered private practice with Riker, Danzig, Scherer, Hyland & Perretti. Without Vanderbilt’s mission to revive the role of lawyers as unselfish public leaders, Stewart Pollock’s legacy — and that of others to come — might have been quite different.

Women Rally for Admission

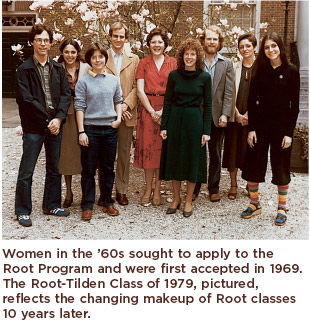

In the years that have elapsed since the earliest classes of scholars graduated, the law has undergone radical changes, as in 1963 when the U.S. Supreme Court decided in favor of Clarence Earl Gideon. In validating the right to free counsel in criminal cases, this decision created public defender offices across the country. Gideon broadened the scope of public service/public interest law, as did developments such as Ford Foundation funding for law reform organizations and the emergence of legal services offices. These advances, combined with the Vietnam War abroad and civil rights battles at home, ushered in a new era, during which the absence of women Roots became a frontline issue at the Law School.

That the inclusion of women was overdue was evidenced by the fact that some women just assumed they were eligible candidates and applied to the Program. In fact, one woman applicant had an ambiguous name and was inadvertently selected to be interviewed for the Program. Consideration was revoked when she arrived on campus and the administration saw that she was, quite plainly, not a man. Though most people were in favor of admitting women Roots, it was not until the end of the ’60s that this change occurred.

According to Janice Goodman (’71), it took power in numbers to lead a campaign for the inclusion of women into the Program, and in this respect the campaign had direct ties to the Vietnam War.

According to Janice Goodman (’71), it took power in numbers to lead a campaign for the inclusion of women into the Program, and in this respect the campaign had direct ties to the Vietnam War.

“I was part of the entering class of 1968, which was between 30 and 35 percent female,” she says. “The class before mine was about 10 percent women, but our numbers grew significantly because the government was no longer giving draft deferments for men in law school, so they were going elsewhere.”

The increasing number of women led to the formation of the Women’s Rights Committee, and as a member, Goodman rallied for the inclusion of women Roots. The administration had long operated by the misconception that allowing women into the Program would violate the terms of a trust agreement. In fact, when the matter was explored further with the Avalon Foundation, its representatives said that including women was not prohibited. The Women’s Rights Committee built its case and took it to the administration, which was overwhelmingly on their side. The scholarship began accepting women in 1969.

Erica Steinberger McLean (’72) was one of three women Root Scholars admitted that year, and while the “odd woman out” when it came to having a Root roommate in the dorms, she did not feel on the outs in any other respect. It was a natural progression to have women in the Program, not a radical change. The Program was made stronger for having advanced and adapted along with social and economic changes.

Days of Struggles

In the 1970s, a hotly politicized era, it became commonplace for law students to use their education to advocate for change within the Law School as well as on matters of domestic and international policies. This atmosphere of reform led to a period that is often described as the Program’s “mid-life crisis.” Students and members of the administration began to question the structure and value of the Root-Tilden Program as it was originally conceived, and often clashed in their opinions of how it should move forward.

Part of the “problem” was that Vanderbilt’s dreams had been realized. NYU School of Law had established itself as a national law school in no small part because the Root Program had attracted the “best of the best” students from every region of the country, elevating the caliber and expanding the geographic composition of the entire Law School. It was no longer necessary to waive tuition to attract top students, and the Law School had less need to recruit from the judicial circuits to achieve geographic diversity.

Most challenging, however, was the question of whether Roots should be obligated to take jobs in the public sector, be they with government agencies or nonprofit organizations. This question spoke to the Program’s philosophical core, as well as a changing financial reality.

“In 1967, a Root-Tilden Scholarship, which paid for full tuition, room and board, books, and a monthly allowance, was worth about $10,000,” Thomas Brome says. “The average salary to work for a firm was about $7500 a year and a legal aid salary was about $6500.”

By 1970, economic conditions in the country had changed. The income gap between many public and private sector positions began to increase dramatically, and tuition costs shot up. Financial support for Root Scholars was reduced to the cost of tuition with no additional stipend.

In hindsight, this moment in history is marked by unfortunate irony. Just as opportunities for lawyers to serve the public interest multiplied and broadened in scope, rising tuition costs made public service/public interest scholarship programs harder for law schools to sustain, and debts harder for graduates to pay. The widening income gap demanded that new sacrifices be made by lawyers who took public service jobs, and many top students nationwide were frustrated by what often seemed like a choice between earning a decent living and doing the work they believed to be important. These changes placed great pressure on the Root Program, as people began to question the validity of a program that funded the entire education of someone who might end up taking a highpaying job with a private firm. How could this be justified to loan-strapped alumni who weren’t in the Root-Tilden Program, but who worked in low-paying public sector jobs after graduation? And yet, how could the Program mandate an absolute definition of what was, and was not, a job that served the public interest?

Retooling for the Future

This crisis of the early ’70s inspired then-Dean Norman Redlich to appoint a special review committee in 1978 to evaluate the Program. This committee recommended that the dean appoint an administrator to reform the Root-Tilden Program. Another committee was formed in 1980, chaired by Professor Norman Dorsen. Its review of the Program was presented in the Dorsen Report, which has become the governing document for today’s Root Program. The report began by reaffirming the four major premises that Vanderbilt set forth:

• The scholarship should not be used as a general scholarship based solely on academic record.

• The scholarships should be awarded nationally, divided as equally as possible among the judicial circuits.

• The scholarships should be awarded by selection committees that include nonacademics, such as federal judges and public service practitioners.

• The scholarships should promote a curriculum beyond what is normally required by the Law School and foster a sense of public responsibility.

The committee then offered several recommendations. It stated that Root applications should filter first through the Law School admissions process and then through several additional screenings, with attention to a student’s geographic location, academic achievements, and commitment to public service/public interest work.

In another recommendation, the committee addressed recruitment based on the judicial circuits. While the Program’s reputation drew applicants from around the country, the committee continued to support the judicial circuit model to continue to ensure a broad geographic distribution in the Program.

The committee also saw it as essential for the Program’s survival that it live within its financial means, and to that end, the committee recommended that scholarship amounts be reduced to two-thirds tuition; the change was implemented in 1984.

While the committee addressed the question of whether students who went through the Program could, in good conscience, take jobs in the private sector, it was not able to entirely resolve it. In exploring the philosophical side of this issue, the Dorsen Committee asked: Is it morally justifiable, in the modern age, for recipients of a merit-based scholarship to accept high-paying jobs in the private sector?

First, the committee acknowledged that “young people develop and alter their perspectives,” which could mean entering the private sector despite having enrolled with different intentions. Further, the committee was not convinced that working outside the private sector necessarily meant working for the public interest, saying:

“Would an ardent environmentalist regard a lawyer for a construction union who argues for Westway or a lawyer for the Mountain States Legal Foundation who urges fewer restraints on strip mining as public interest lawyers?”

The Dorsen Report did not attempt to simplify this extremely loaded issue, but to ease tensions it suggested that an explicit payback system be instituted, so that a Root who made enough money was morally obligated to repay the scholarship as if it were a loan. This suggestion paved the way for the income-based loan repayment assistance programs that were developed later for non-Roots. In recent years, the debate over Root career choices has been addressed by an explicit moral obligation stating that Root graduates who earn a salary above the prevailing public interest salary should repay their scholarships.

The question of what defines public service and public interest, however, remains open, and perhaps always will be. However, the Root-Tilden-Kern Program, as the pioneer in public service scholarship programs, has worked through its growing pains and matured, allowing it to remain relevant and respected today.

“We have the widest range of public interest programming of any law school in America, and a central part of that is the visibility that the Root Program has received in the last 50 years,” Professor Thompson says.

Because NYU School of Law is so well known for its extraordinary program in public interest law, the Root Scholars have now become completely integrated into the extensive public interest community at the Law School. The activities sponsored by the Program, like the Monday Night Speaker Series, are open to all Law School students. Additionally, Thompson points out that tuition funding is available for the general population of students who enter public sector positions.

“What we are able to do with Roots on the front end, we are able to do for other public interest students on the back end, with loan repayment,” he says.

Continuing the Success

Currently, the Law School is involved in a financial campaign initiated by Jerome Kern (’60), whose name was added to the Program’s title in 1999. Kern, along with NYU Board of Trustees Chair and former Law School Board Chair Martin Lipton (’54) and Herbert Wachtell (’54), both Root graduates, and Leonard Rosen (’54) and the late George Katz (’54) founded Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen, Katz & Kern in 1963. Kern is now a Law School trustee and chief executive officer of Kern Consulting. He donated $5 million to the Program, and jump-started the campaign to raise $25 million more to ensure the future and continued renown of the Program.

Kern is among others who would like the Program to be able to again offer full-tuition scholarships to 20 students each year. The Root-Tilden-Kern endowment campaign is well under way and, based on the positive progress so far, those involved in the campaign expect to meet the $30 million goal.

Kern’s support and continued involvement with the Program is, he says, inspired by the caliber of the candidates.

“I served on a selection panel four years ago and I was amazed by the quality of the

people who were applying for it, forget about those who won it,” he says.

Today’s Root-Tilden-Kern Scholars graduate from a top law school with an honor that has been celebrated for five decades. Three recent Root alumni, Alex Reinert (’99), Andy Siegel (’99), and Monica Washington Rothbaum (’99), clerked for U.S. Supreme Court justices and the list of prestigious public interest fellowships that Root and non-Root students at the Law School receive annually is, in a nutshell, very, very long.

“The Program enhances NYU School of Law’s reputation among the top law schools in the country, but it also provides a great public service,” Kern says. “It would be greatly satisfying to see it get more support from the universe at large.”

On Course for Another 50 Years

Stewart Pollock also sees the future of the Program through a wide lens.

“The horizons of the law, and therefore NYU School of Law, have expanded over the past half-century, and hence the public interest that graduates can serve has also expanded,” he says, explaining that he would accept a categorization of his own career in public service as provincial. “NYU School of Law students generally, and Roots in particular, now have the opportunity to serve on a much larger stage, in this country and other countries.”

Pollock admires the late Supreme Court Justice William Brennan’s philosophy about interpreting the U.S. Constitution as a living document, and he believes that the constitution of the Root-Tilden-Kern Program should be interpreted in kind — as relevant to the time in which we live. “The next generation will be fulfilling their obligation as 21st-century lawyers,” Pollock says.

True to Vanderbilt’s ideals, the Root-Tilden-Kern Scholarship Program continues to foster a great tradition of public service within the legal profession. As the Program celebrates the 50th anniversary of its first graduating class in 2004, it is fitting that a new Program director, Deborah Ellis (’82), and a new faculty director, Professor Vicki Been (’83), both Root graduates, have taken the helm (see p. 80), setting the Program on course for a centennial celebration.

Multimedia

Multimedia