From Darkness

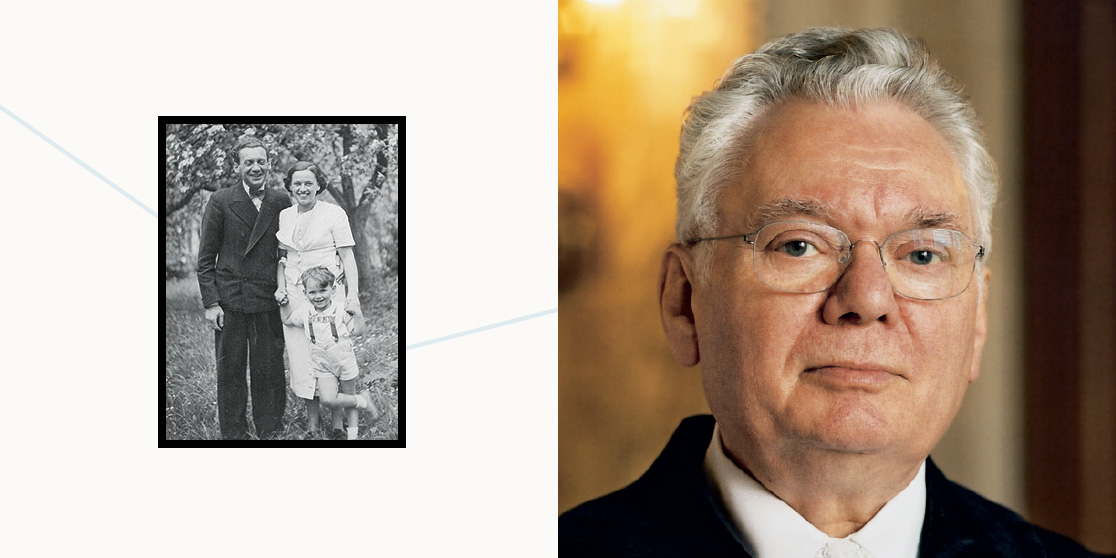

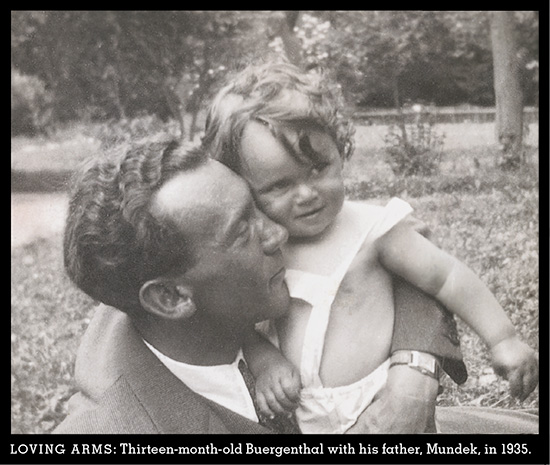

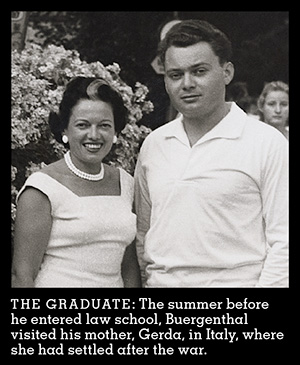

Printer Friendly VersionThomas Buergenthal ’60 has a picture of himself and his parents taken in the spring of 1937. He is three, a blond, curly-haired boy who looks into the camera with the serene assurance of a well-loved child. His mother, Gerda, short and dark-haired, wears a suit; his father, Mundek, a tall man in a jacket and bow tie, wraps his arm protectively around his wife. The three of them look happy. In fact, they were a family on the edge of an abyss.

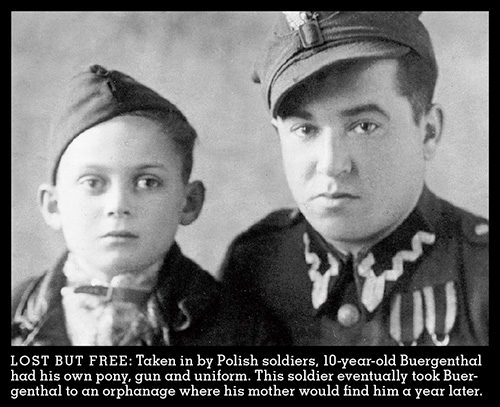

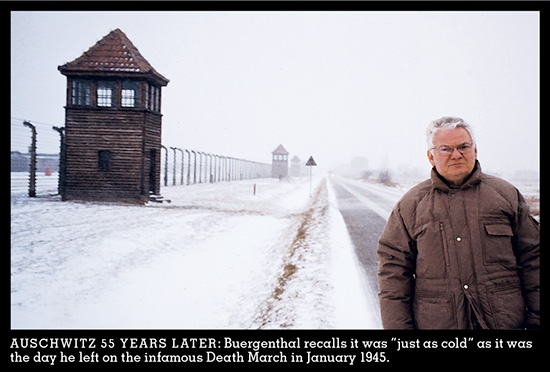

Shortly afterward, the family’s hotel in Lubochna, Czechoslovakia, was seized by the local Fascist militia and the Buergenthals escaped to Poland, where they applied for English visas. On the day Hitler invaded, they were on a train bound for the border with the visas in hand—only to have their train bombed. They wound up in the Jewish ghetto of Kielce for several years, surviving two massacres. Eventually, they were sent to Auschwitz, where Buergenthal was separated from his parents. About a year later, when the camp was evacuated in January 1945, he was among a group of prisoners who made the 44-mile trek across the frozen Polish countryside that later came to be known as the Auschwitz Death March. Buergenthal was 10 years old, one of only three children who survived. Mundek Buergenthal was executed by the Nazis at Flossenburg in the last days of the war. Gerda Buergenthal survived and spent the next 18 months searching for her son before finding him in a Polish orphanage run by a Jewish relief group.

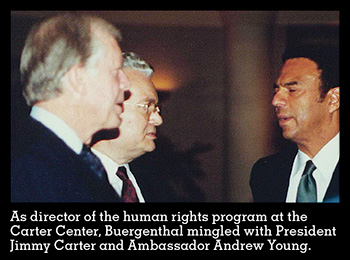

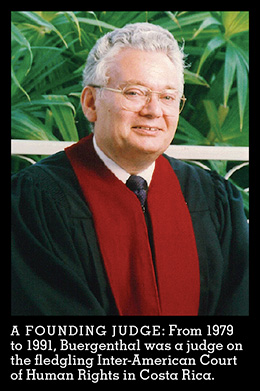

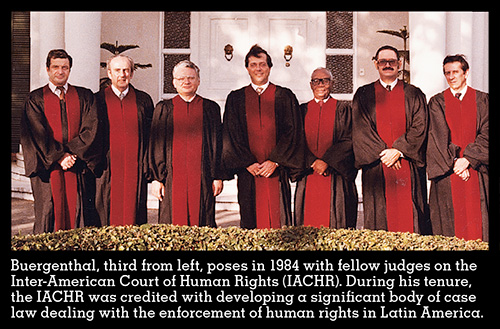

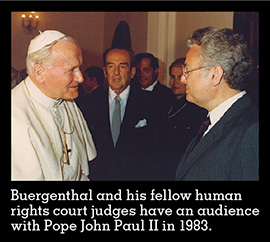

Today, the boy who survived all that is a 74-year-old, white-haired judge on the International Court of Justice (ICJ) at The Hague—the principal judicial organ of the United Nations and an increasingly busy forum for international disputes that range from boundary feuds to the death penalty. In the decades between then and now, Buergenthal has emerged as one of the main architects of the legal institutions and procedures needed to apply the abstract concept of “human rights” to real-world problems. In 1979, he was elected to a judgeship on the Costa Rica-based Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR), the most important human rights tribunal in Latin America; in 1990, he served on the U.S. delegation to the first postCold War conference in Europe, helping to draft standards for democratic elections in newly formed Eastern European nations; in 1992, he was appointed to the U.N. Truth Commission for El Salvador. In 1995, he became the first American to be elected to the U.N. Human Rights Committee.

Clearly, it’s been a remarkable life. Yet outside academia, the U.N. and the State Department, Thomas Buergenthal is not a household name, which seems a little strange. How could anyone have accomplished so much from such bleak beginnings and not have the kind of fame enjoyed by, say, fellow Holocaust survivor and Nobel Peace Prize-winner Elie Weisel?

The comparison is inevitable: After decades of false starts, Buergenthal has finally managed to put his life story on paper. Ein Glückskind (Lucky Child) describes some of the same events as Weisel’s classic 1958 Holocaust memoir, Night—and despite the hundreds of Holocaust books that have been written in the last 60 years, Ein Glückskind quickly hit the best-seller list in Germany, where it was first published in 2007. So far it’s sold more than 100,000 copies in Germany and is currently in print in nine countries, with British and American publication set for early 2009. Germany, the country that once stripped Buergenthal of his citizenship, is now eager to lionize him: Suddenly, there are television interviews, audio books to record, invitations to be honorary this or that, even the dedication of a library named for him in his mother’s hometown of Göttingen.

Writer Krista Tippett has observed, “Goodness prevails not in the absence of reasons to despair, but in spite of them. People who bring light into the world wrench it out of darkness, and contend openly with darkness all of their days.”

“After all you have seen,” I asked him, “do you really think a species seemingly intent on self-destruction is also capable of creating a coherent, enforceable jurisprudence of human rights?”

The man who has witnessed so much of that darkness has an unhesitating reply: “I don’t have any doubt.”

Full Disclosure

Thomas Buergenthal is an old friend of mine. We met in 1985 when I was the legal affairs reporter for the Atlanta Constitution, fresh from the Master of Studies in Law program at Yale Law School. He had just been named director of the newly established Human Rights Program at the Carter Center in Atlanta, a position that came with a teaching post at Emory University School of Law. He had also just been elected chief justice of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, a body I’d never heard of. I went to his office at Emory and met a short man whose meticulously groomed curly hair reminded me of my father’s, and whose perfect manners were more formal than the casual Southern friendliness I was used to. We did a brief interview about the Carter Center’s new program, which frankly didn’t interest me much, and after a while I stood to leave. As I did, he asked—almost shyly—“Would you like to know a little bit about my childhood?” I sat back down.

I heard only the most truncated version of his story that day, but even so, it was difficult to grasp that the child who had experienced such horrors and the man sitting across from me were one and the same. As it happened, Buergenthal had on his bookshelf the English translation of the memoirs of Odd Nansen, the Norwegian author and humanitarian, who had met Buergenthal when they were both prisoners at Sachsenhausen after the evacuation of Auschwitz. Buergenthal showed me the book’s dedication, which was to the millions of victims of the Holocaust—“and especially you, little Tommy.”

“That’s me,” he said, smiling. “Now you know why I’m doing human rights law instead of international business law.”

I wasn’t familiar with either field, but I knew a remarkable witness to history when I met one. Not long after, I invited Buergenthal and his wife, Peggy, over for dinner and cooked my best “company” meal, roast leg of lamb, which they seemed to relish. Years later, Buergenthal confessed that the smell wafting from the kitchen when he and Peggy walked through my door had nearly made him retch: For years after the war, the only meat available had been mutton. Unwittingly, I’d served him something he’d sworn off forever.

That kind of diplomatic fortitude is an occupational requirement for a judge at the ICJ, where the most mundane cases—a complaint from Argentina, say, about pollution from a Uruguayan pulp mill—arrives bristling with international political tensions. The 15 judges on the court, who hail from a variety of backgrounds, must interpret and apply legal precedents that are still relatively new compared to most common law concepts, and do it while maintaining at least the appearance of collegiality. Buergenthal finds this relatively easy: He is unassuming, multilingual (he speaks German, English, Polish, Spanish and a little Italian), knowledgeable about other cultures and always eager to learn more. On days when the ICJ is in session or he is working in his office at the court’s headquarters in The Peace Palace in The Hague, he usually lunches with his fellow judges in their private dining room.

He also brings heavyweight scholarly credentials to the task. He wrote the book on post-war human rights law—literally: His 1973 text International Protection of Human Rights, coauthored with Louis B. Sohn, was the first American casebook on the subject, and paved the way for introducing human rights into law school curricula across the country. Subsequent books, written with George Washington University Law School professors Dinah Shelton and David Stewart, are required reading for students in the field.

Within his field, Buergenthal is famous. But the community of international human rights legal scholars is relatively small, and the field as a whole suffers from an image problem. Most Americans associate the phrase “human rights” with the word “violation.” Bombarded as we are with stories about Abu Ghraib, the murderous fanaticism of the Taliban or tribal warfare in Kenya, it’s easy to conclude that the state of human rights today is a sorry mess.

That would be the short view. The long view is that progress in human rights law since World War II has been “phenomenal,” said Murry and Ida Becker Professor of Law Emeritus Thomas Franck, and he repeated the word for emphasis: “phenomenal.”

One of the lesser-known facts about the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials at the end of World War II is that they specifically excluded acts in which the victims were German citizens, Franck noted. Why? Because at the time, what a government did to its citizens was considered purely a domestic concern. Genocide was viewed in the same way wife-beating used to be: a distasteful matter outsiders were well advised to ignore.

But just as domestic violence is now considered an urgent social problem, “there has been a sea change in the fundamental issue, which is that how a government treats its citizens is no longer considered purely a domestic matter,” Franck said. A formidable body of human rights law has sprouted in a mere half century from a seed planted in the ruins of World War II. Among other things, the charter of the United Nations pledges “international cooperation in…promoting and encouraging respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language or religion.” That was followed by the passage of the Convention against Genocide, better known as the Geneva Convention, and the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

But what, exactly, are “human rights”? Over the ensuing decades, the exacting work of defining the term and the methods by which its protection would be enforced was left to a variety of U.N.-created commissions and to the bodies that interpreted international conventions, such as those barring torture or race discrimination.Another body of law evolved within the framework of agencies like the U.N. Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) or the International Labor Organization, both of which incorporate human rights protections into their charter.

World events also played a role: The bloody civil wars that erupted in the 1990s in Yugoslavia and Rwanda spawned tribunals to try individuals charged with crimes against humanity, genocide and war crimes (the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, for instance). The credibility those tribunals established led, in turn,to the creation of the International Criminal Court in 2002. Over the same period, three regional human rights judicial systems were evolving: the European Court of Human Rights (established in 1953), IACHR (1979), and the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (2006).

Buergenthal’s major contribution has been in Latin America. The United States is not a party to the convention that created the IACHR, but Costa Rica is. That nation nominated Buergenthal, who had already established himself as an expert in regional human rights tribunals, and his U.S. nationality helped boost the fledgling institution’s credibility.

Credibility is no longer an issue. The IACHR has established an extensive body of case law dealing with the enforcement of human rights in Latin America, on issues ranging from state censorship to violent political repression. It was the first international tribunal to hold a state financially liable for waging a campaign of “forced disappearances” against its political opponents. In that 1988 ruling, the court ordered the government of Honduras to pay restitution to the families of the victims during that country’s civil war earlier in the decade. The ruling was itself remarkable; even more remarkably, the government of Honduras complied.

Since then, IACHR case law has taken root in the constitutions of more than 20 countries in Latin America. The result has been a dramatic increase in recent years in the number of human rights cases initiated by governments themselves against the actions of previous regimes. Case in point: the 1998 detention of General Augusto Pinochet, the former Chilean dictator, in London, and his subsequent prosecution on charges of systematic human rights abuses during his 16-year rule. Since then, similar cases have been brought in Mexico, Uruguay, Brazil and Peru, marking a radical shift toward accountability in a part of the world with a long history of repressive military dictatorships.

“When I came to Latin America, you couldn’t really even talk about human rights,” Buergenthal said, and it’s clear from the frequency with which the subject of Latin America comes up in conversation that he regards his tenure on the IACHR as one of the most satisfying periods of his career. Though it would be hard to single out Buergenthal’s single most important contribution to human rights law, his IACHR work would be at or near the top, colleagues say. “He’s had a role in improving the well-being of an awful lot of people,” said GWU Law Professor Sean Murphy. Human rights law may be an esoteric topic to most people in the United States, “but in Latin America, it’s in the papers every day.”

The Immigrant Becomes a Citizen

Buergenthal arrived in this country in 1951 aboard a ship crowded with European refugees, carrying one suitcase and a smelly $50 bill in his shoe—a 17-year-old high school student whose years of missed elementary school education had been only partially remedied by private tutoring. He lived with an aunt and uncle in Paterson, N.J., and, despite his initial handicaps, graduated in the top quarter of his class. After high school, he accepted a scholarship to Bethany College, a small liberal arts college in West Virginia.

In his senior year at Bethany, the school recommended him for a Rhodes Scholarship to study law at Oxford University. After making it through the first selection round, he arrived at the final interview unprepared and babbled aimlessly. That ended his Rhodes prospects, but one of the interviewers was impressed enough to slip him a note advising him to apply to NYU’s Root-Tilden Scholarship Program. Buergenthal did, and not only won a scholarship, but also a stipend covering room, board and books. The stipend, Buergenthal said, made all the difference: Even with an academic scholarship, he simply did not have any money to live on. “Without it, I wouldn’t have been able to go to law school,” he said.Buergenthal recalls his first year of law school as a tough academic transition, though it was eased by life in Greenwich Village, in those days a small town that just happened to be in the middle of a busy metropolis. He roomed at Hayden Hall with Alan Norris, now a senior judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit in Columbus, Ohio. Norris, who is still a close friend, recalled that he and Buergenthal had little in common in terms of politics, but his roommate cheerfully tolerated the oversized picture of Republican Senator Robert Taft that Norris hung in their room.

Buergenthal’s fellow law students remember him as friendly, but no party animal. “He never went out with the boys drinking, but he always had time for an event,” says John Blyth, a New York real estate lawyer who met Buergenthal when one of their professors seated the incoming students in alphabetical order. And though Buergenthal never made much of it, “after a while everybody knew about his background in the camps,” Blyth said. “Nobody ever said much about it.”

In his third year at NYU, Buergenthal married Dorothy Coleman, who had been a fellow student at Bethany College. Over the next 19 years, the couple raised three sons while Buergenthal pursued an academic career that took him to the University of Texas as well as American, Emory and George Washington universities. His marriage to Coleman ended in 1981. Two years later, he married Peggy Bell, a Peruvian-born conference interpreter.

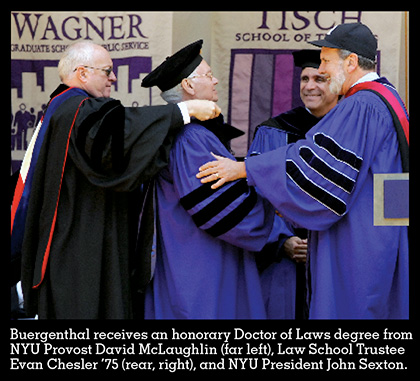

Aside from his rocky introduction to law school, Buergenthal said, he has warm memories of his time at NYU—in particular, of Robert McKay, the constitutional law scholar who would later become dean. “My best friends to this day are fellow Root-Tilden students who also lived in Hayden Hall,” he said. His association with the school continues: The international law program that has developed since Buergenthal’s days now sends students each year to work as interns at the ICJ.

If he were a baseball umpire, Buergenthal would be described as having a consistently narrow strike zone. He goes where he thinks the law goes, even when U.S. foreign policy and/or its military and political strategies go another way—that far, and not an inch further. His circumspection is partly a product of his history, says Sean Murphy: “He is sensitive to the perception that because of his Holocaust experiences there might be some who would question whether he could be impartial.”

Buergenthal’s judicial perspective is often invoked in procedural terms. In 2003, for instance, a majority of the court ruled that the United States illegally invoked a national security rationale for destroying three offshore oil platforms owned by Iran in 1987 and 1988. Buergenthal differed—not because he sided with the U.S. on the merits, but because in his view the court lacked jurisdiction to address the issue. The same year (2003 was notable for the number of controversial ICJ cases) the U.N. General Assembly asked the ICJ for an advisory opinion on whether Israel was justified in erecting a wall along the Green Line in occupied Palestinian territory on the West Bank. In a 14-1 ruling, the ICJ held that Israel was not, with Buergenthal as the holdout.

But his opinion was not exactly pro-Israel. Instead, he argued that the ICJ should have stayed out of the dispute altogether because the evidence submitted to it by the General Assembly glossed over the history of rocket and mortar attacks on Israel launched from the Palestinian territories. Then he made an even finer distinction: Even assuming that the court had ample evidence before it that Israeli citizens were victims of Palestinian rocket attacks, “a state which is the victim of terrorism may not defend itself against this scourge by resorting to measures international law prohibits.” A careful weighing of Israel’s security needs versus the rights of the Palestinian people along each section of the wall would be needed, and might well show that some sections violated international law while others did not.

“He has convinced the invisible college of international law that he really does care about the law,” said Franck, who has been a friend and colleague for 40 years. “He’s understated, he’s relatively quiet and unassuming, he’s made it absolutely clear that he calls the shots as he sees them. He never tries to bully or dominate or wave a big stick…. When the law coincides with [what] the United States [wants], he will call it that way, but if the law doesn’t support what the United States wants, he’ll go with the law, and everybody knows it. It gives him a kind of clout.”

In the Israeli wall case, Buergenthal implicitly criticized his colleagues for ignoring certain facts to fit their ruling when he wrote that the humanitarian needs of the Palestinian people would have been better served if the ICJ majority had taken a complete factual record into account, “for that would have given the Opinion the credibility I believe it lacks.”

Yet neither judicial reticence nor artful phrasing can conceal Buergenthal’s profound differences with the Bush administration’s approach to international law and human rights. In 2003, he joined a unanimous ICJ ruling that said the U.S. violated an international treaty by not telling 51 Mexican citizens held on death row in U.S. state prisons that they had the right to seek legal help from their government. The Bush administration demonstrated its displeasure by withdrawing from the convention under which it had agreed to accept ICJ jurisdiction. Even so, President Bush ordered state courts to comply with the ICJ ruling. On March 25, though, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 that Bush’s order had exceeded the authority of the executive branch. Unless Congress explicitly said as much, the majority ruled, international treaties cannot supersede state law. The case seemed over—but in June, Mexico asked the ICJ to temporarily halt Texas’ execution plans. In response, the ICJ asked the U.S. to “take all measures” necessary to delay the executions while it considered the request. But on August 5, Texas proceeded with the first execution.

In an era when political differences often devolve into personal attacks, it’s worth noting that people who vehemently disagree with Buergenthal’s views—and there are many—confine their attacks to his opinions. A recent post on a blog devoted to ICJ matters, for instance, was scathingly critical of an ICJ opinion “written by your friend and mine, Tom Buergenthal.” Still, conservative animus to Buergenthal’s views runs deep. He was nominated to the ICJ by the outgoing Clinton administration to fill out the unexpired term of his predecessor, then renominated in 2006 by the Bush administration. But that appearance of bipartisan support is deceiving. Conservatives in the State Department were outraged by Buergenthal’s rulings in the oil platforms case and by his less-than-vigorous dissent in the Israeli wall case.

“The ICJ in my view has gone out of its way to find actions in violation of international law,” said Edwin Williamson, a former legal adviser to the State Department under the administration of President George H.W. Bush. U.S. judges nominated to the ICJ are vetted by the State Department and approved by the president before their names are forwarded to the U.N. General Assembly, where approval is usually pro forma. Buergenthal’s renomination might not have made it that far if not for the support of former Secretary of State Colin Powell, who argued that he was both qualified and electable, an important consideration at a time when relations between the United States and the United Nations were at a low point over the war in Iraq.

Even then, the Bush administration may have felt it had no choice but to renominate him. ICJ procedures also say that judges can be nominated by any ICJ member country; Buergenthal won the support of a record number of 32 nations. “He would have been elected anyway,” Franck said. “And to have been elected anyway as the American judge on the court, without having the nomination of the United States, would not have been very good politics.”

What the State Department didn’t know, said one source who asked for anonymity, was that Buergenthal would not have accepted the appointment without the backing of his own country. As critical as he is of U.S. foreign policy under the Bush administration—it has “totally destroyed our credibility on human rights,” he said—Buergenthal takes his U.S. citizenship very seriously. Classmate John Blyth recalls that Buergenthal became a citizen while the two of them were at NYU. On the next election day, Blyth said, “the polls opened at 6:00 a.m., and he was there at a quarter to six. And he was the first to vote.”

Remembering the Holocaust

On an unusually springlike evening last February, I went with the Buergenthals to a reception at the Israeli embassy in The Hague. It was given by Ambassador Harry Kney-Tal and his wife, Nili, in honor of Israeli writer Aharon Appelfeld, whose latest book had just been published in Holland. The three of us squeezed into seats near the back of the room as Appelfeld—a balding, diminutive man dressed completely in black—kept the crowd rapt with tales of his own youth during the Holocaust.

As the reception was breaking up, Peggy urged her husband to introduce himself. Peggy grew up in a bilingual household in Peru, and speaks with a charming accent that, to my ears, sounds like Zsa Zsa Gabor’s. (“No,” Buergenthal corrected me when I told him this. “Eva Gabor. She was the one I always had a crush on.”) Now “Eva” was doing a wifely full-court press. “You must talk to him,” she said. “You must tell him about your book.”

“No,” Buergenthal demurred. “There are so many of these books, Peggy.” Just then, Nili Kney-Tal came up and put her hand on Buergenthal’s arm. “I so wish you had asked a question!” she exclaimed, and Buergenthal shrugged, smiling. He seemed slightly embarrassed. But after a few moments, he edged his way through the dense crowd around Appelfeld, and these two children of theHolocaust had a brief chat out of our earshot.

“What did you talk about? Are you going to send him a copy of your book?” Peggy asked excitedly as we were putting on our coats in the foyer. “Oh, I don’t know,” Buergenthal muttered. Peggy gave me a look as if to say: husbands.

The incident illustrates something that has bedeviled Buergenthal for much of his life. While he has always felt a strong urge to tell his story—he showed Blyth an early draft when they were law students, and he mentioned his desire to write his memoirs on the day I met him—it’s been painfully difficult for him to find his voice. For one thing, he had doubts about his writing ability. His youngest son, Alan, 40, a lawyer who works for a health care company in Columbus, Ohio, regards his father as “a great legal author” whose logical presentation is “always a pleasure to read.” But narrative prose is a very different genre.

“As one whose prior writing experience has been limited to law books and legal articles, I found writing this book very difficult, and not merely because of the subject,” he wrote me in an email last fall. “As a result I am quite insecure about the quality of the book, that is, whether it conveys what I wanted to convey.”

Then there are the comparisons that will inevitably be made between Ein Glückskind and Night. Though they were at Auschwitz at the same time, Buergenthal and Weisel first met several years ago at an event at the U.S. Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. Their accounts of the Death March are strikingly similar.

Otherwise, the books could not be more different. Night is a primal howl of anguish written when Weisel was only 30 and his memories still raw. Written in 2006, Ein Glückskind is the work of a 72-year-old man looking back over half a century. It is less a memoir of the Holocaust than it is the story of how a child’s moral intelligence was refined in the cauldron of that horrifying event.

It also has a broader scope. Like Weisel, Buergenthal describes concentration camps that were “laboratories for the survival of the brutish.” Unlike Weisel, he also describes generosity and acts of heroism. Weisel asked how God could have allowed such things to happen; Buergenthal asks how people could have allowed it. “What is it in the human character that gives some individuals the moral strength not to sacrifice their decency,” he writes, while others “become murderously ruthless?” How could such brutality be inflicted by such ordinary people—men who would “go home in the evening to their families, wash their hands before sitting down to dinner as if what they had been doing was a job like any other”?

A reader might hope that age and wisdom have given Buergenthal insights that eluded the youthful Weisel, but not so. Buergenthal seems as stymied by these questions as Weisel—more so, in fact, since the intervening years have shown too clearly that the Holocaust was hardly a singular event. As a teacher or a judge, he can be exacting, a stickler for the precise word, the correct phrase. But he has no answer to the mystery of human evil, and he is uncharacteristically inarticulate when it comes to exploring the emotional landscape of his experiences. Ein Glückskind is remarkable not just for the dramatic events Buergenthal has lived through, but also for the number of questions it cannot answer.

“The insanity of it all is hard to fathom,” he writes, and the book is peppered with a similar kind of detached bewilderment: “Generalizations about the Holocaust, about German guilt or about what Germans knew or did not know, do not help us understand the forces that produced one of the world’s greatest tragedies.” And: “I have often wondered why or how I managed to survive the camps.”

Buergenthal says that he wept at times while he was writing Ein Glückskind—but overall, the book keeps the reader at arm’s length from the events it portrays, and there is a sense that the psychological armor that helped protect the child is now a hindrance to the adult writer. Perhaps it’s unavoidable. In one chilling passage, he recounts how he used to sleep in a barracks so close to the gas chambers at Auschwitz that his sleep was often interrupted by the screams of the people being forced inside. After a while, he found a way to cope—by what psychologists call “lucid dreaming.” Hearing the screams, he would say to himself in his dream, “This is only a nightmare, there is nothing to be afraid of.”

Yet the person who emerges from the pages of Ein Glückskind is not a tortured soul, but an irrepressible, mischief-making boy. During his years in Kielce, Buergenthal and his friends would play tricks on the peasant women who tilled the land in the vacant lot behind their apartment building: They would hide until the women stopped to urinate in the field, standing in their long skirts with their legs spread apart. At just the right moment, the boys would yell or bang on a pot to startle the women in midstream, so to speak. Then the children would run, laughing, pursued by Polish curses.

As an adult, Buergenthal’s brand of humor tends toward the droll understatement. Norris, his old roommate, recalls that every man at NYU in the 1950s was draft bait—except for Buergenthal, who was exempted because he had lost two toes to frostbite during the Death March. Every year, Buergenthal would get a notice from the draft board inquiring about his physical fitness; every year, he would write back: “My toes have not yet grown back.” Blyth recalls a party where Buergenthal gave an impromptu performance of the Polish national anthem. He knows how to have fun: Buergenthal’s former colleague Murphy recalls a dinner at his home when Buergenthal wowed Murphy’s children with his prowess at ping-pong.

At the same time, he is a deeply serious person. Alan jokingly says that “the only way he truly let us down as kids” was by nixing a family trip to Disney World, which his father thought was a waste of time. Robert, who is 45 and works as a senior counsel in the Justice Reform section of the World Bank in Washington, D.C., remembers that at family dinner “every child reported on his schoolwork and there was always an issue to discuss.”

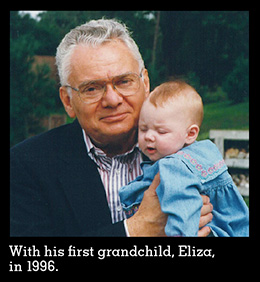

Buergenthal and his sons have a running argument about how much he told them about his childhood. Buergenthal says his children never showed much interest. His sons emphatically differ, but say what they learned came in bits and pieces. “If you asked questions, he’d always answer,” Alan said. At other times, information would emerge in odd ways; once, Robert said, his father told him that he’d been unable to carry Robert around as a baby because of a back injury he suffered during a beating in the camps. Buergenthal spoke far more easily about his grandparents, murdered by the Nazis in 1942, or his mother, who remarried after the war and lived in Italy, with frequent visits to this country, until she died in 1991.

When Robert was in junior high school, he read Night. “I told Pop it sounded a lot like his stories, and I asked him to read it,” Robert said. The answer was no. To this day, his father avoids Holocaust literature and movies depicting the period. When Slaughterhouse Five became a movie in 1972, Robert remembers, his parents came home from the theater early; his father could not bear to watch it.

“Until this book, no matter what he may say, he never walked us through his history,” said Robert. And yet the proverbial elephant was always in the room: “Everything about him was shaped by the war or the Holocaust.”

A Sustaining Faith in the Law

One day in the fall of 1944, the prisoners at Auschwitz were called to assemble for one of the many “selections” the Nazis performed to get rid of prisoners unfit for work. One by one, the prisoners walked before a panel of doctors—a group which may have included Mengele himself, though Buergenthal will never know for sure; he was too terrified to look up. He followed his father in the line, looking for an escape route. At the head of the line, the doctors ordered Mundek Buergenthal to go left and his 10-year-old son to go right. Mundek grabbed his son, but a guard tore the boy away while another kicked the elder Buergenthal out the barracks door. It was the son’s last glimpse of his father.

Buergenthal was taken to another barracks, where all the other prisoners were old, sick or succumbing to starvation—clearly, destined for the gas chamber. So was he; children were considered unfit for manual labor, and it was a miracle he had survived this far. Three times over the next few hours, Buergenthal managed to escape through the back door of the barracks; three times, for reasons he still finds unfathomable, the other prisoners alerted the guards that he was escaping. Finally—baffled, angry, overcome with grief and fear—he sat down against the wall in a corner.

Until then, I had been gripped with fear, fear of dying. But then something most unusual happened. Slowly, very slowly, my fear and anxiety faded away….An inner warmth streamed through my body. I was at peace, my fear had vanished and I was no longer afraid of dying.

“I can’t explain it,” he said to me.

We were sitting in his office in The Hague, located in a modern building next door to the ornate 19th-century edifice where the court holds its hearings. Through a window left slightly open to the springlike air, I heard a distant hum of traffic; a pair of Nile geese floated on a pond outside.

Was it a spiritual experience? I pressed. “No,” he said. His family was never observant, and his experiences in the war eliminated any vestige of a belief in the Divine. The best way he can describe that moment was that it was the intense realization that “death is always just a moment away.” Which, in a way, is a spiritual epiphany—but the moment passed, and in the years since he has never totally recaptured it.

Alan Norris has told him that it was more than just cosmic coincidence that on the day Buergenthal was chosen for the gas chamber, the ever-efficient Nazis did not have enough prisoners to justify firing up the crematorium—just as it was more than coincidence that a Polish camp doctor later secretly altered his identity card, saving his life. Buergenthal disagrees. His survival, he says, was simply luck. “I admire people who are religious—well, not the extremes—but I don’t believe in a personal God the way some people do,” he said. “I wish I could. It would give me strength.”

Yet, in a way, the absence of one kind of faith has left room for another: a faith in the power of law. The law is no panacea, he concedes; it has never prevented terrible things. But it can at least be a “no trespassing” sign posted at the edge of the abyss. There are reasons to think this is a useless gesture: Cambodia, Rwanda, Bosnia, Darfur. But, Buergenthal points out, the same decades that brought us those events have also brought the end of apartheid, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the replacement of autocratic regimes with democratically elected governments in Latin America, a proliferation of international tribunals and a growing number of nations willing to comply with their rulings.

On a trip to Columbus last year, Alan told me, his father was looking through some family photos with Alan’s seven-year-old daughter, Ruth, and explaining to her how so many of their relatives had died, why their extended family was so small. The next day, Alan said, Ruth went to her first-grade class “and she told what she could about what happened to my father, and the kids said, ‘Oh, you’re lying, people don’t do things like that for no reason.’”

But people have, and probably will again. Meanwhile, Buergenthal shows up for work every day at a court with a steadily growing caseload. The years are passing, and he would like to spend more time with his grandchildren. But his work is not finished; it may never be. Building a jurisprudence of human rights is like building the Taj Mahal, or the pyramids of ancient Egypt: The goal is ridiculously ambitious, the work takes decades, and the craftsmen labor in anonymity. Even then, the results are imperfect, and susceptible to vandals and the passage of time.

What’s most amazing about those wonders, though, isn’t how well they have survived. The most amazing thing is that anyone ever thought of building them in the first place.

—Freelance journalist Tracy Thompson wrote The Ghost in the House: Motherhood, Raising Children and Struggling with Depression (HarperCollins, 2006). Recently she contributed to the anthology The Maternal Is Political (Seal Press, 2008).

—