Bryan Stevenson’s Death-Defying Acts

Capital punishment, that contentious old emblem of the American criminal-justice system, is under fire. In recent months, California and Maryland followed eight other states in suspending operation of their death chambers. In 2006, the number of executions nationwide dropped to 53, the fewest in a decade, as governors, legislators and even some prosecutors questioned whether the ultimate punishment can be administered fairly and humanely.

And so, one might assume that a conversation with Bryan Stevenson, the celebrated death penalty defense lawyer and professor, might have an upbeat, even triumphant tone. One would be incorrect.

Capital punishment, that contentious old emblem of the American criminal-justice system, is under fire. In recent months, California and Maryland followed eight other states in suspending operation of their death chambers. In 2006, the number of executions nationwide dropped to 53, the fewest in a decade, as governors, legislators and even some prosecutors questioned whether the ultimate punishment can be administered fairly and humanely.

And so, one might assume that a conversation with Bryan Stevenson, the celebrated death penalty defense lawyer and professor, might have an upbeat, even triumphant tone. One would be incorrect.

Stevenson arrives late, apologizing. A fundraising appointment uptown dragged on longer than expected and, he intimates with a sigh, could have gone better. We walk from his modest campus office to a Middle Eastern café near Washington Square Park. When I note all the recent news on the death penalty, Stevenson’s face creases with concern. He worries about complacency among foes of capital punishment, while more than 3,300 people remain on death row. He detects “innocence fatigue” among media outlets, which he fears are no longer interested in covering the justice system’s myriad flaws unless the story ends with the vindication of a long-suffering inmate. “9/11 had a role in this,” he says. “The country had a huge new concern, a new fear. There was a new prison narrative in Abu Ghraib and Guantánamo…. All of these things have tended to eclipse concern about the death penalty.”

Stevenson, in sum, feels no reason to rejoice. He stays on message with an impressive discipline. He wants to talk about Anthony Ray Hinton, a condemned man he currently represents on appeal in Alabama, where Stevenson runs a nonprofit law firm called the Equal Justice Initiative, or EJI. Hinton has served 20 years on death row, convicted of a pair of robbery-murders at fast food restaurants near Birmingham. Stevenson says Hinton is innocent and received a capital sentence only because he is black and poor and couldn’t afford a decent trial attorney.

In full advocate mode now, Stevenson cites statistics from Alabama and the nation as a whole, showing that a murder defendant is more likely to get the death penalty if he’s black and the deceased is white. Stevenson speaks calmly, in carefully crafted sentences. “The real question,” he says, “isn’t whether some people deserve to die for crimes they may have committed. The real question is whether a state such as Alabama, with its racist legacy and errorplagued system of justice, deserves to kill.” He thinks not.

Since his days as a law student at Harvard, Stevenson, who is 47 years old, has inspired breathless awe for his commitment and idealism. Randy Hertz, the director of clinical programs at NYU and one of Stevenson’s best friends, acknowledges that the adulation at times seems implausible. But, Hertz says, “when you work closely with Bryan and spend a lot of time with him, what you discover is that the stories about him that seem like they must be apocryphal—the brilliance, the round-the-clock schedule, the selfless devotion to others—are absolutely true, and if anything, probably too understated.” Cathleen Price, a senior attorney who works for Stevenson at EJI in Montgomery, says he stands out even within the tiny fraternity of die-hard death-penalty lawyers. The labor is draining; the pay, poor. “You decide in each year whether you can go on for another year—how much sacrifice you can give versus the great need for the work,” explains Price, who’s been with EJI since 1997. “But Bryan doesn’t seem to think that way. His life is the work and the sacrifice. It’s what he wants. He is unique.”

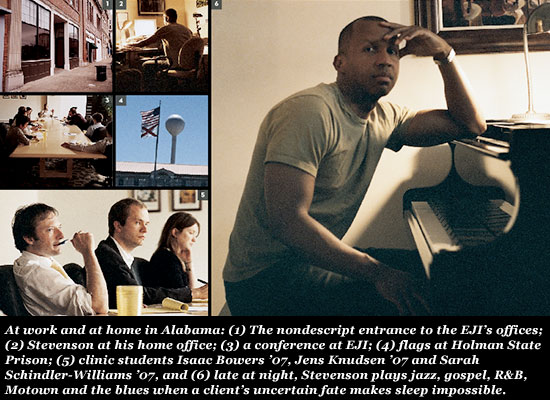

Stevenson has mixed feelings about all the wonderment. Single and famously ascetic, he admits that apart from family, everyone close to him comes from his professional circles. He doesn’t know any of his neighbors in Montgomery, where he has lived for nearly 20 years. Outside of the EJI office, a spacious downtown building next door to the Hank Williams Museum, Stevenson says he feels wary and unwelcome. The Confederate flags flown by some businesses and homeowners rankle him, as does a popular bumper sticker: “If I had known it would turn out like this, I wouldn’t have surrendered,” attributed to Confederate General Robert E. Lee.

On the topic of sacrifice, he can get a little defensive. “To me it was completely fortuitous that I found something that I was so energized and jazzed by,” he insists. “I think it became a lifestyle because it seemed like it was that way for the people I initially met” doing death-penalty work. “But it didn’t seem like a lifestyle that was out of balance…. Nothing felt sacrificial.”

It becomes clear during a series of conversations over several months that the roots of Stevenson’s singular dedication—a term he might prefer to sacrifice—trace back to a childhood influenced by the African Methodist Episcopal church. The gospel of lost souls seeking redemption echoes in his memory. “I believe each person in our society is more than the worst thing they’ve ever done,” he sermonizes in nearly every appearance, his voice intense yet controlled, his cadence that of a preacher in full command of a congregation. “I believe if you tell a lie, you’re not just a liar. If you take something that doesn’t belong to you, you’re not just a thief. And I believe even if you kill someone, you are not just a killer. There is a basic human dignity that deserves to be protected.”

Identifying that shard of dignity became Stevenson’s own form of redemption, his means of achieving a personal state of grace, though in his unusual life, the liturgy of litigation has replaced communal worship: He rarely finds time anymore to attend church. His exertions produce results in the secular realm. EJI has helped reverse the death sentences of no fewer than 75 Alabama inmates over the past two decades. He has argued twice before the Supreme Court of the United States and received practically every award a liberal civil rights attorney could receive.

For all that, though, Stevenson is not a man free of doubt. Sometimes, when he’s not standing in front of an appellate court or an audience of law students, he quietly admits to a measure of uncertainty over how to map the second half of an extraordinary career. He is looking beyond capital punishment, determined to broaden his focus. He has begun to seek redress for inmates condemned to life in prison for crimes committed when they were 13 or 14 years old. This and other new forays have him redoubling his fundraising, expanding his 19-person organization, and feeling more than typically stretched as he juggles teaching in New York, litigating in Alabama, and speaking across the country. “It’s harder and harder to assess what you can do and what you want to do,” he concedes. “My vision of the needs of the world gets bigger and bigger.”

Born in 1959, Stevenson grew up in rural Milton, Delaware, a border area more a part of the South than the North. Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 Supreme Court case that condemned segregation in public education, was slow to reach southern Delaware, and Bryan spent his first classroom days at the “colored” elementary school. By the time he entered the second grade, the town’s schools were formally desegregated, but certain old rules still applied. Black kids couldn’t climb on the playground monkey bars at the same time as their white classmates. At the doctor’s and dentist’s office, black children and their parents continued to enter through the back door, while whites went in the front. White teenagers drove past black homes, the Confederate flag flying from one car window, and a bare behind sticking out another one. “Niggers, kiss my ass!” they shouted.

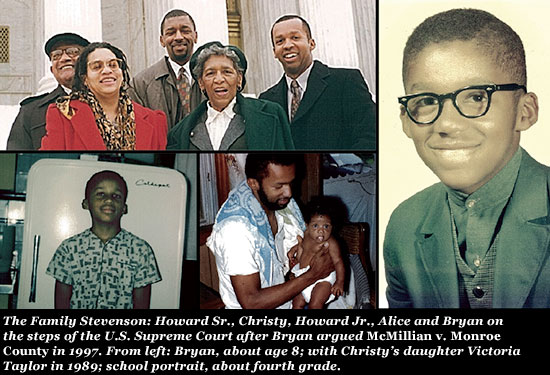

Bryan’s father, Howard Stevenson, Sr., worked at the General Foods processing plant. Mr. Stevenson had grown up in the area—his female relatives worked as domestics for white families— and he took the ingrained racism in stride. “He’d pray for people and say God would deal with the bad ones,” recalls Bryan’s older brother, Howard, Jr. Their mother, Alice Stevenson, was a different story. A clerk at Dover Air Force Base, she had grown up in Philadelphia, where the constraints on African Americans were less oppressive. She bristled at the routine bigotry she encountered in southern Delaware. When Bryan was automatically placed, along with the other black children, in the slowest of three groups in second grade, his mother wrote letters and objected in person until he was moved up to the previously all-white accelerated group. When white supermarket clerks placed her change on the counter instead of directly into her hand—a gesture she interpreted as a racial slight—she demanded, “You give me my money!”

Alice Stevenson’s “message was, ‘Don’t let people mistreat you because you’re black,’” says Howard Jr. “She was very direct: ‘If someone speaks the wrong way, you speak back. If someone hits, you hit back.’” This wasn’t theoretical advice. In elementary school, the Stevenson brothers, often allied with an Hispanic classmate, did fight with white boys who came at them swinging. Bryan translated their mother’s eye-for-an-eye philosophy into a career of legal combat. Howard, a noted Ph.D. psychologist and associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Education, researches the socialization of African American boys, although with the goal of steering them away from violence.

Alice Stevenson inherited her fierce dignity from her mother, Victoria Golden, the daughter of slaves from Virginia and family matriarch. Bryan, Howard, and their younger sister, Christy, visited their grandmother regularly at her home in Philadelphia. Victoria’s word was law that no one questioned. When she took young Bryan aside one day and asked him never to touch alcohol, he promised he wouldn’t. Four decades later, he still hasn’t.

But not all of the extended family served as a source of pride. Bryan and his siblings had an uncle who died in prison, and the children rarely saw Victoria Golden’s husband, their grandfather Clarence. In contrast to his abstinent wife, Clarence had been a bootlegger during the Prohibition era and also did time behind bars. Known for his sharp wit and wiliness, Golden drifted away from his family and as an old man lived alone and poverty-stricken in a public housing project in south Philadelphia. One day some teenagers broke in to steal his television. When he resisted, they stabbed him to death. He was 86; his grandson Bryan, 16.

The murder intruded on the remarkable bubble of achievement in which Bryan thrived. His parents, steadily employed, provided a more comfortable life than that of most of the family’s rural black neighbors. Bryan excelled at Cape Henlopen High School, bringing home straight A’s and starring on the soccer and baseball teams. He performed the lead role in “Raisin in the Sun,” the play about a striving working-class black family. He served as president of the student body and won American Legion public-speaking contests. His grandfather’s brutal death reminded Bryan how different his family was from those of the middle-class white kids he mingled with at school. Until adulthood, he never spoke of the killing in public. “I didn’t want anyone to know about some of these realities that were unique to people living at the margins,” he says.

Church was the place where a young Bryan made sense of how the fulfillment he derived from early success could coexist with the racism and poverty he observed around him. The family attended the Prospect African Methodist Episcopal Church where Bryan’s father played a prominent role. At special testimonial services, members of the congregation stood one by one and competed to confess the lowest sin. “God delivered me from alcohol,” one would say to light applause. “God delivered me from drugs,” said the next, as excitement built. “If you said you had been in prison, you got even bigger applause,” Stevenson recalls. “The more you had fallen, the more you were celebrated for standing up.” Here were the beginnings of his belief that people are defined by more than their worst act.

Worship had another dimension for Bryan. His mother played piano and encouraged her children to listen to music, especially gospel and jazz. Bryan, it turned out, could pick up songs by ear and taught himself to play the beat-up old piano his mother kept in their home. His family appears to have taken this in stride, along with his other talents. By the age of ten, he was accompanying the gospel choir at Prospect AME. “Playing piano gave him confidence in front of an audience,” his brother, Howard, says. “He became a performer.” When the choir toured the state, Bryan went along.

His repertoire expanded to include blues, Motown, and R&B. “Stevie Wonder and Sly and the Family Stone were favorites,” Howard recalls, “in part because of the way they combined their music with themes having to do with right and wrong in society, and injustice.” Kimberle Crenshaw recalls Bryan’s piano playing drawing a crowd of black teenagers during breaks in a 1976 conference for student leaders in Washington, D.C. Crenshaw, like Stevenson, was 17 then, and has been a friend ever since. “His music—he was playing gospel and spiritual—created a space for other African Americans who came from a church background,” she says, “and that led to discussions of social and racial issues. He was not loud, not boisterous. He was as firm and resolved as a 17-year-old could be.”

A year later, Stevenson followed his older brother to Eastern University, a Christian school in Pennsylvania with a vibrant music program and a strong soccer team. He majored in political science and philosophy and directed the campus gospel choir. For a time, he dreamed of a career playing piano or professional sports. But as the years went by, he realized that a life on the road might be less than glamorous. He says he chose law school without much thought. “I didn’t understand fully what lawyers did,” he admits.

His brother sees a natural progression from precocious musical performer to high school debater to professional advocate. Howard even takes some credit for helping hone Bryan’s rhetorical skills: “We argued the way brothers argue, but these were serious arguments, inspired I guess by our mother and the circumstances of our family growing up.” Bryan headed for Harvard Law School.

He arrived in Cambridge in the fall of 1981, he says, “incredibly naïve and uninformed.” His only prior visit to the Boston area was with his college baseball team. The local fans had shouted slurs and thrown bottles at the black players from Eastern University, forcing the game to end early. While his classmates at Harvard Law School were friendly, he never felt comfortable among students who for the most part were from more privileged backgrounds. “I stopped almost immediately trying to fit in,” he says. “I thought about it more like a cultural anthropologist,” trying to figure out the customs of a tribe in whose midst he found himself. Subjects like property, torts, and civil procedure seemed abstract and distant. “I just found the whole experience very esoteric,” Stevenson says.

The arcane suddenly became relevant, even urgent, when he traveled to Atlanta for a month-long internship in January 1983— part of a Harvard course on race and poverty. He worked for an organization now known as the Southern Center for Human Rights. “For me, that was the absolute turning point,” he says—of both his time at Harvard and his nascent legal career. The center, led by a dynamic young attorney named Stephen Bright, engaged in a caseby- case war against the death penalty. Bright threw his inexperienced Harvard intern into pending appeals on behalf of death-row clients whose trial lawyers, out of either ignorance or negligence, hadn’t put on much of a defense. “He is brilliant, quick, and speaks with eloquence and power,” says Bright. “That was apparent from when he was a student here. It was obvious that his natural skills gave him an advantage over many practicing lawyers.”

Stevenson read transcripts that revealed trial attorneys failing to offer either witnesses or closing arguments. He reviewed briefs devoid of legal analysis. “I could do better,” he thought. “It really did change the way I thought about law,” he explains. “All of a sudden, the more you knew about procedure, the more you could problem-solve for someone who had a good claim that had been procedurally barred. The more you knew about the substantive law, the more likely you would be to come up with ten other options for this person to get a new trial.” In both of the cases he worked on that January, the clients eventually had their death sentences set aside and received prison terms instead. “It did seem to me you could actually do something,” he says. From that point forward, he thought of himself as a death-penalty lawyer.

Kimberle Crenshaw ended up being a classmate at Harvard Law. She and other black students focused on such campus issues as integrating the faculty. Stevenson sympathized but kept his distance, she says. “He was kind of ahead of the curve, looking beyond the law school, focusing on the disenfranchised and how to use the system to fight for them.” Crenshaw now teaches civil rights law at Columbia University and UCLA.

Returning to Bright’s center after graduating from Harvard, Stevenson relished everything about the role of being a staff attorney at a public-interest organization: the life-and-death stakes, the long hours, the sense of mission, even the low pay. “The lawyers,” he says, “seemed passionate and engaged and completely focused on the problems of people on death row, who were literally dying for legal assistance.” For about a year, he slept on Bright’s couch, which Stevenson recalls as lumpy. (“It couldn’t have been too lumpy,” Bright responds, “because he slept on it a long time!”)

Joking aside, Stevenson stresses how important near-poverty became to him. “Nobody got paid any money, or at least very little,” he says, “and that struck me as the ultimate measure of something genuine.” In contrast to the fancy corporate law firms that charmed so many of his Harvard classmates, he says, “it became clear to me that these death-penalty folks were real. They were serious.”

Stevenson had discovered a cause in correcting injustice. He also found an inner path to authenticity by denying himself the material trappings of the professional class. “If monks were social activists, that is what he would be,” observes Crenshaw. “There are people who do what he does when they’re 20 or 30, but by the time they’re 40 or older, they’re usually looking for at least some creature comforts…. There is a spiritual element to it for Bryan, something otherworldly about it. I can’t quite put my finger on it.”

In an interview published last year by the Christian magazine PRISM, Stevenson elaborated on this theme. Noting that after Harvard he could have had any legal job he wanted, the publication asked why he chose a death-row practice. “For me, faith had to be connected to works,” Stevenson answered. “Faith is connected to struggle; that is, while we are in this condition we are called to build the kingdom of God. We can’t celebrate it and talk about it and then protect our own comfort environment. I definitely wanted to be involved in something that felt redemptive.”

By the time Stevenson moved from Cambridge to Atlanta in 1985, the campaign against the death penalty had seen its greatest breakthrough in Furman v. Georgia (1972), the culmination of a series of challenges charted by Anthony Amsterdam, now University Professor at NYU School of Law. (See “A Man Against the Machine.”) The Supreme Court had reinstated capital punishment in 1976. The tiny corps of lawyer-activists appealing death sentences thereafter sought narrow victories based on specific facts. They crafted arguments that a defendant’s childhood deprivation, physical mistreatment or limited mental capacity, for example, hadn’t received sufficient attention at trial.

As Stevenson familiarized himself with such obscure subspecialties as obtaining an emergency stay of execution, the issue of race surfaced in case after case. Black defendants were overrepresented among the condemned, and murders of white victims seemed to lead prosecutors to seek death sentences.

Outside the courtroom, Stevenson was frequently reminded of his own race. One weekend, he glanced out the window of the supermarket where he shopped and noticed a rally in the parking lot. Members of the local Klavern of the Ku Klux Klan had gathered to promote white prerogatives.

On another occasion, he was sitting in his parked car at night, listening to Sly and the Family Stone on the radio before going inside to his apartment. A passing police cruiser stopped, and an officer ordered him out of his car. When Stevenson, who was wearing a suit and tie, stepped out, the nervous white policeman pointed his gun at the 28-year-old black lawyer and shouted, “Move, and I’ll blow your head off!” Another officer threw Stevenson across the hood of his car and conducted a fruitless search. Neighbors came out to watch. Frightened and enraged, Stevenson clung to long-ago advice from his mother: don’t challenge angry white cops. The police eventually let him go without so much as a parking ticket. Months later the Atlanta Police Department officially apologized, but only after Stevenson had filed an administrative complaint and implied he might follow up with a misconduct suit.

During this period, Amsterdam and other anti-death-penalty strategists decided to try another frontal constitutional assault. They selected a case from Georgia and asked the Supreme Court to declare the death penalty unconstitutional once and for all because it systematically discriminated on the basis of race.

McCleskey v. Kemp, decided in April 1987, involved a black man, Warren McCleskey, sentenced to die for killing a white police officer during the course of a furniture-store robbery. Stevenson, a junior lawyer on the McCleskey team, helped with legal research. The McCleskey lawyers based their appeal on a study of more than 2,400 homicide cases in Georgia in the 1970s. The research indicated that Georgia juries were 4.3 times more likely to impose the death penalty if the victim is white—and that the odds only got better if the victim is white and the killer is black.

The Supreme Court rejected the argument, 5-4. Writing for the majority, Justice Lewis Powell didn’t dispute the statistical showing but said that McCleskey’s lawyers had failed to offer evidence specific to his case that showed racial discrimination. “Apparent disparities in sentencing are an inevitable part of our criminaljustice system,” Powell observed. “McCleskey’s claim, taken to its logical conclusion throws into serious question the principles that underlie our entire criminal-justice system.” Justice William Brennan Jr. responded in dissent that “taken on its face, such a statement seems to suggest a fear of too much justice.”

When he heard the result, Stevenson wasn’t surprised that the high court refrained from striking down the death penalty across the board. But he had hoped for a ruling that would at least require Georgia and other states with records of racial misdeeds to apply capital punishment more cautiously. “What was shocking,” he says, “was the majority’s comfort level in justifying these racial findings, which they didn’t question; they accepted them.” Georgia executed Warren McCleskey in 1991, and most death-penalty litigation then returned to parsing alleged procedural defects in trials.

Two years after the decision in McCleskey, Stevenson accepted another death-penalty case suffused in race, but one unencumbered by lofty debate about statistics. The raw injustice at the core of Walter McMillian’s case catapulted Stevenson into the national consciousness as a gifted and passionate capital defender.

At Bright’s request, Stevenson was spending an increasing amount of time in Alabama in the late 1980s, helping with litigation concerning the abysmal conditions of the state’s prison system. Stevenson also agreed to represent a batch of Alabama death-row inmates. McMillian, a 45-year-old pulpwood worker with only a misdemeanor bar fight on his record, had been convicted in 1988 of the murder two years earlier of an 18-year-old dry-cleaning store clerk. He was black; she was white. The case played out in Monroeville, best known as the home town of Harper Lee, author of “To Kill a Mockingbird,” the best-selling novel published in 1960 about racial injustice in a Southern small town dominated by Jim Crow.

Stevenson says he didn’t take the case because he thought Mc- Millian was innocent. Most death-row inmates, including most of his clients, he says, are guilty of something, if not necessarily the precise charges that led to their sentences. But the taint of racism in the McMillian case piqued the lawyer’s interest. First there was the sentimentalized reverence that Monroeville’s citizens had for “To Kill a Mockingbird.” They wore their association with the book as a badge of honor, when in fact the work was meant as an indictment. “It was clear to me when I got there that very little of the book had sunk in,” Stevenson deadpans.

The sociology of the place was highly relevant because of McMillian’s local reputation. Though married to a black woman, he had crossed a sacrosanct line by openly having an affair with a white woman. Making matters worse, one of McMillian’s grown sons was married to a white woman. “The only reason I’m here is because I had been messing around with a white lady and my son married a white lady,” McMillian told the New York Times.

The evocatively named Judge Robert E. Lee Key had moved the trial from Monroe County, which was 40 percent black, to Baldwin County, which was only 13 percent black. The jury of 11 whites and one black heard testimony from three prosecution witnesses implicating McMillian. Foreshadowing the outcome, the authorities had held McMillian for months before trial on Alabama’s death row. The two-day trial ended in conviction, and the jury imposed a sentence of life imprisonment. Judge Key overrode the sentence, as Alabama’s law permits, and sentenced McMillian to death. Key described the crime as the “vicious and brutal killing of a young lady in the first full flower of adulthood.”

As he began to investigate the case, Stevenson found McMillian’s friends and neighbors suffering from what he interpreted as a form of group depression. The verdict, he says, “was incredibly debilitating to people of color and to poor people in that community,” because so many of them knew that the defendant’s alibi was true. Defense witnesses at trial had placed him at a fish fry 11 miles from the killing. “I think it felt like an indictment and a prosecution of an entire community,” Stevenson says.

Then he came across the defense lawyer’s dream: police files improperly concealed at trial. Within those files was an audiotape, and on that recording were the voices of officers coercing the main prosecution witness to testify falsely that he saw the killing. All three witnesses for the state eventually recanted. But shockingly, Judge Key refused to throw out the conviction.

Stevenson “was sure that McMillian was innocent,” recalls Bright, “but the setting in which he had to investigate the case and present his arguments could not have been worse.” Stevenson received telephone death threats at his home and office in Montgomery. Meanwhile, Alabama’s appellate courts refused to act.

Stevenson decided to try another sort of appeal. Working with Richard Dieter of the Death Penalty Information Center, a clearinghouse in Washington, D.C., the attorney arranged to meet a producer from the CBS newsmagazine show “60 Minutes.” Dieter recalls the session at an outdoor restaurant: “Bryan was warm and affable as always, but he got right to the point. He told the story of his client’s innocence and the prosecution’s manipulation of the case through inaccuracies and racial taint. With Bryan weaving the story, it was spellbinding. After he finished, the producer said, ‘If even half of what you are telling me turns out to be true, we’ll be down in Alabama in a few days.’” The newsmagazine aired a devastating piece. “Just the presence of this show in Monroeville caused the legal wheels to start turning,” Dieter says.

The Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals, which had earlier brushed off a series of appeals on McMillian’s behalf, now unanimously threw out his conviction. In March 1993, Walter McMillian left his cell, a free man. “We told the court when we were here a year ago that truth crushed to earth shall rise again,” Stevenson told the Times. “It doesn’t necessarily mean we believe in the judicial system.” Dieter today identifies Stevenson’s victory in the McMillian case as “the start of a long series of innocence cases that has led to the present rethinking of the death penalty.”

Stevenson never gained faith in Alabama’s judicial system, and even as he fought the McMillian case, he suffered one of his most poignant defeats. Soon after moving to Montgomery in 1989 to open the predecessor agency to the EJI, he received a collect call from Holman State Prison. A death-row inmate there had heard about the young lawyer and decided to plead directly for help. His story was a grisly one. The inmate, an emotionally disturbed Vietnam veteran named Herbert Richardson, had left a homemade bomb on the porch of a woman he was stalking. The bomb exploded and killed not the woman, but a little girl from the neighborhood.

Richardson’s execution was only 30 days away. Stevenson recalls telling him there was nothing he could do: “I’m sorry, but we don’t have staff, we don’t have books.” Richardson called back the next day, begging. The lawyer finally agreed to do what he could. He gathered some documents on the case and filed for an emergency stay of execution. “But,” he says, “it was too late.”

On Richardson’s execution day, Stevenson drove to Holman so he could keep his client company during the final hours. An innocent child had died, the lawyer acknowledges. But Stevenson’s thoughts focused on the inmate, whom he believed had been in the grip of mental illness. Richardson made an observation that has haunted Stevenson ever since. All day long, people had asked the condemned man what they could do to help. Prison officials gave him special meals, all the coffee he wanted, and stamps for farewell letters. “More people have said ‘What can I do to help you?’ in the last 14 hours of my life, than they ever did in the first 19 years of my life,’ ” Richardson said to his attorney.

Stevenson tells this story in many of his speeches. He asks rhetorically where those attentive Alabama officials had been when Richardson was being physically and sexually abused as a child, when he became a teenage crack addict, and when he was homeless on the streets of Birmingham. “With those kinds of questions resonating in my mind,” Stevenson says, “this man was pulled away from me, strapped in Alabama’s electric chair, and executed.”

Even fellow death-penalty activists marveled at Stevenson’s decision to leave Atlanta for Montgomery. “Many law school graduates go to a place like Montgomery for a couple of years— maybe four or five—which is wonderful,” says Bright. “But Bryan has gone way beyond that.”

Stevenson thought little of it. “What might have intrigued people was that there was no clear ‘get’ if you were going to spend all your time helping really hated people in the deep South,” he says. “What you’re going to get is a lot of contempt and hostility, maybe disrespect and a lack of appreciation from your immediate environment.” His life was already so Spartan—a barely furnished apartment; 14-hour work days, seven days a week; only occasional socializing—that the Montgomery move didn’t seem like much of an additional deprivation. Many types of law practice, not just at a fancy corporate firm, would have fattened his bank account. Almost any other kind of job would have left more time for a personal life. He wanted none of it. When the board of directors of the nonprofit Capital Representation Center in Montgomery offered him $50,000 as a starting salary, he insisted on taking only $18,000.

His parents for a long time had difficulty comprehending his commitment. “They were a little mystified by what I was doing and why,” Stevenson admits. Being a lawyer was fine, but why did he have to represent people accused of such horrible crimes? Why did he have to work so many hours? Aware of this consternation, Stevenson years ago gave his parents a videotape of a speech in which he explained to an AME church convention why he represented men on death row. He quoted the Bible, Matthew 25:34-40, in which it is predicted that in Heaven, Jesus will say to the righteous:

Come, you who are blessed by my Father; take your inheritance, the kingdom prepared for you since the creation of the world. For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in, I needed clothes and you clothed me, I was sick and you looked after me, I was in prison and you came to visit me.

The righteous, perplexed, will ask Jesus when they had fed Him, clothed Him, or visited Him in prison. And Jesus will reply: “I tell you the truth, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers of mine, you did for me.”

Hearing their son put his work in a Christian context allowed Alice and Howard Stevenson to understand why Bryan had decided to spend his life in the service of men on death row. Around the family, “he never talked about himself,” Alice Stevenson told the Washington Post before her death in 1999 at the age of 70. “Me, I’ve been a money-grubber all my life,” Mrs. Stevenson continued. “But now that I’ve been sick, I see that Bryan is right. Really, what are we here for? We’re here to help one another. That’s it.”

Media coverage of the McMillian case brought Stevenson a measure of fame. Accolades began to accumulate, including, in 1995, a $300,000 “genius” grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Stevenson says he passed all the money along to his nonprofit legal center in Montgomery, which at the time had an annual budget of $500,000.

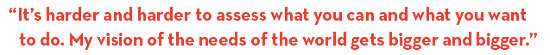

Law schools, including NYU, invited the now-prominent Stevenson to lecture and teach. He enjoyed interacting with students and saw hands-on legal education as an effective way to train public-interest lawyers. John Sexton, then dean of the NYU School of Law, made an extraordinary offer: Stevenson could teach alongside the legendary Amsterdam and continue to run the EJI, shuttling back and forth from Montgomery to New York. The Law School would provide generous funding to support students and recent graduates to work for Stevenson in Alabama. In other words: lots of free labor.

Stevenson asked Amsterdam for advice. Amsterdam answered with a question: Will it advance the interests of your clients? Concluding it would, Stevenson became an assistant professor of clinical law in 1998 and five years later, full professor. He teaches three classes: Race, Poverty and Criminal Justice; Capital Punishment Law and Litigation, and the Capital Defender Clinic, which includes three months at the EJI in Montgomery. Amsterdam coteaches the New York portion of the clinic. Stevenson gives part of his NYU salary to EJI and lives on the rest. He takes no pay from the EJI.

What began as an unconventional experiment has paid off for all concerned. “The Law School has been a really great partner,” Stevenson says. He has benefited from the work of dozens of students like Aaryn Urell ’01. A native of southern California, Urell encountered Stevenson soon after she arrived at NYU. “People in the public-interest community all said, ‘Oh, you have to go hear Bryan speak. You won’t believe how inspiring this guy is.’” Urell had a master’s degree in international peace and conflict resolution and had done human rights work in Africa. She had heard rousing speeches, but the Stevenson talk was different: “He spoke about serving the despised, the poor, the abused, people without resources and all alone and abandoned in a system set up to work against them….I resolved on the spot to work for him.”

During the summer after her first year, she worked at EJI in a public-interest internship funded by proceeds from a student-organized annual auction. She returned for spring break her second year. “They couldn’t get rid of me,” Urell says. She took Stevenson’s two classroom courses in New York and then spent much of the fall semester of her third year in the clinic in Montgomery. Eight students at a time work in the clinic, an intensive experience which includes reinvestigating the cases of death-row clients and drafting appeals. After receiving her J.D. in 2001, Urell returned to Montgomery as one of two NYU-sponsored postgraduate fellows at EJI. When that two-year program ended, she signed on as a staff attorney and continues in that capacity. “It’s a privilege to work on these cases and to serve these clients and their families,” she says.

Stevenson teaches students an array of formal and informal legal lessons. They draft appellate briefs and learn the Southern etiquette needed to negotiate with Alabama court clerks. He instructs them never to call any adult—especially clients and their family—by their first names, always “Mr.” or “Mrs.” He also teaches them that remaining silent is sometimes the best way to get a reluctant witness to revisit a long-ago murder case. “Generally people do want to tell you their stories. You need to let them,” says Matthew Scott ’07, who worked at EJI in the spring of 2007 and plans to become a public defender.

In her first summer at EJI, Urell investigated a series of robberyshootings at fast food restaurants from Birmingham to Atlanta. “We spent a lot of time in the car, I’ll tell you that,” she recalls. Her goal was to demonstrate that the distinctive crimes—during which the robber forced restaurant managers into walk-in freezers and then shot them—continued even after an EJI client accused of two of the crimes had been arrested and taken off the street.

That client is one of Stevenson’s top priorities at the moment because the lawyer believes he can prove the man innocent. Anthony Ray Hinton was arrested in 1985 and charged with two of the fastfood murders. No eyewitnesses or fingerprints placed him at either crime scene, but he was identified by a victim who survived a third restaurant shooting. Strangely, prosecutors never charged Hinton with the third attack. In addition to the victim identification, the state offered expert testimony that slugs from all three crimes were fired from a .38 caliber revolver recovered from Hinton’s mother.

At the time of the trial in 1986, Alabama capped compensation for court-appointed criminal trial lawyers at $1,000. Hinton’s trial attorney received only an additional $500 to hire a ballistics expert and ended up with one who was both inexperienced and blind in one eye. The prosecutor tore the unqualified “expert” to shreds, and Hinton was convicted and given two death sentences, which Alabama appellate courts affirmed.

Stevenson stepped into the case in 1999, 14 years after Hinton’s arrest. The lawyer has presented testimony from a trio of well established ballistics experts who say the bullets can’t be definitively matched to one another or to the .38 caliber handgun. (The defense contention that similar crimes continued to occur after Hinton’s arrest—the issue that Urell investigated—has been eclipsed by the ballistics conflict.) Stevenson is now trying to persuade Alabama courts to reopen the case, even though his client has exhausted his direct appeals. Prosecutors are unmoved, arguing in a recent brief: “Hinton was guilty in 1986, and he is still guilty today. Simply wrapping an old defense in a new cover does not prove innocence.”

In April 2006, the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals upheld Hinton’s conviction, 3-2. Stevenson has appealed to the state’s Supreme Court. He points to the cases of Walter McMillian and six other Alabama men freed from death row after they were found not guilty of the crimes that put them there. “With 34 executions and seven exonerations since 1975, one innocent person has been identified on Alabama’s death row for every five executions,” he argues. “It’s an astonishing rate of error.” Nationally, more than 120 death-row inmates have been exonerated since 1973.

Hinton, a former warehouse worker, believes in Stevenson. In a letter from death row, he writes: “I felt that this man went to law school for all the right reason. And that reason was to fight for the poor. Here was a lawyer who knew his purpose as a man!” Hinton adds, “If God create a better man, He keep him for His Self.”

Amazing as it might seem to those with ordinary jobs and ordinary lives, Stevenson wonders about the adequacy of his accomplishments and the reach of his responsibilities. He believes he needs to do more, take new risks.

But is that physically possible? Will he cloud the clarity of his mission and risk confusing those who help fund it? “It’s much simpler if you say, ‘We’re the death-penalty people. We do the death penalty in Alabama,’” he concedes. “But it’s never felt descriptive and accurate. I’ve always considered myself a lawyer concerned more broadly about human rights.”

He’s angry not just about the cloud of injustice he sees hanging over death row, but the wrongs that he contends permeate the entire American criminal-justice system. The country’s prison population has soared from fewer than 200,000 in 1970 to more than 1.3 million. Another 700,000 inmates reside in jail. All told, the United States locks up more than two million people, resulting in the highest per capita rate of incarceration in the world. Nearly one in three black men between the ages of 20 and 29 is in prison or jail or on probation or parole, according to the Sentencing Project, a research and advocacy group in Washington, D.C.

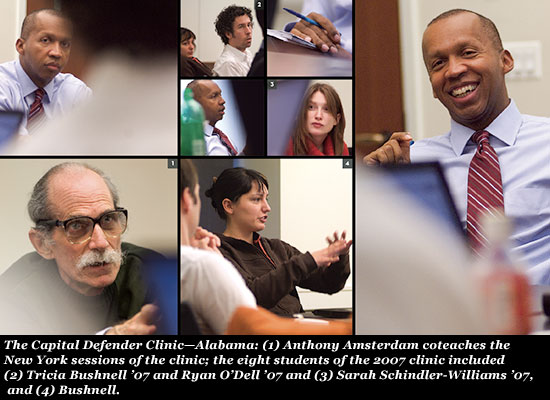

Stevenson is broadening EJI’s mandate to address what he considers to be other egregious aspects of an excessively punitive system. His organization represents inmates in Alabama and elsewhere sentenced to life terms without the possibility of parole under repeat-offender statutes, also known as three-strikes laws. One wall in the EJI offices displays photos of clients such as Jerald Sanders, who was sentenced to life without parole after being convicted of stealing a bike, his third strike. He spent 12 years in prison until EJI won his release in 2006. “Somebody who has three prior rapes and rapes again is not the same as someone with three prior bad checks who writes another one,” Stevenson argues.

He has taken on the cases of some of the dozens of youths serving life terms without parole for crimes committed when they were 13 or 14. “The short lives of these kids will be followed by long deaths as a result of America’s other death penalty: life imprisonment without parole,” he contends. The list of ambitions continues: He wants to challenge laws that ban people convicted of drug crimes from receiving food stamps or living in public housing. He plans to step up civil litigation to combat exclusion of blacks from jury pools. His small nonprofit is already straining. “I’ve had a huge problem keeping folks in Alabama,” Stevenson admits. Of his 18 lawyers and staff members, four now live out of state. He has no office manager or anyone to handle media inquiries. “It’s just a little overwhelming for me right now, trying to do it all myself.”

He has briefed his foundation backers on his expansion plans. His main supporters are the Public Welfare Foundation in Washington and the Open Society Institute in New York. They have been “respectful and concerned,” he says. More specifically, officials at the foundations have asked: “You’ve already got an impossible task. Why are you trying to make it harder?”

Stevenson understands the concern. “You can get kind of overwhelmed by it,” he says, “and you realize you can pick up more than what you can hold.” He also sees how some might conclude that he is trying to diversify as the death penalty appears to recede. But capital punishment isn’t going away anytime soon and certainly not in Alabama, which houses more than 190 people on its death row. In any event, he says, the vicissitudes of capital punishment aren’t driving his decision to branch out.

The impulse to right a broader array of wrongs comes from within. It is an instinct that he can do more, and therefore must. “Things that are the most rewarding and engaging involve struggle, involve commitment, involve dedication,” he says. “I think those are the key ingredients to that sense of fulfillment.”

Stevenson seems greedy for just one thing: the opportunity to pursue righteous struggles, as he defines them. Unlike most people who understand the personal cost incurred by such a life, he seems eager to pay it.

—New York journalist Paul Barrett is the author of American Islam: The Struggle for the Soul of a Religion (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007) and The Good Black: A True Story of Race in America (Dutton, 1999). He has a J.D. from Harvard Law School.