Creative License

With a series of recent hires, NYU Law’s formidable IP faculty now numbers six. While their expertise ranges across patents, copyrights, and trademarks, the group explores a common question: What best drives innovation?

Printer Friendly VersionIn a unanimous and controversial 2012 ruling, the US Supreme Court held that Prometheus Laboratories could not patent a method of determining whether a patient is receiving an optimal amount of a therapeutic drug. The method relied on correlations between a patient’s response to certain drugs used to treat gastrointestinal disorders and the proper treatment dose.

In the Court’s opinion, Justice Stephen Breyer quoted from an amicus brief authored by Alfred B. Engelberg Professor of Law Katherine Strandburg warning against such patents. If “claims to exclusive rights over the body’s natural responses to illness and medical treatment are permitted to stand,” the brief argued, “the result will be a vast thicket of exclusive rights over the use of critical scientific data that must remain widely available if physicians are to provide sound medical care.”

As technology infiltrates nearly every aspect of our lives, intellectual property issues are growing in importance. They are also becoming more pervasive. During their most recent term, the justices took several major patent cases—including one involving software—as well as a much-watched copyright dispute involving retransmission of television broadcasts. In the not-too-distant future, jokes John M. Desmarais Professor of Intellectual Property Law Barton Beebe, the age-old Property course will largely revolve around the ownership of things like inventions and expressions rather than land and goods.

With an eye to the 21st-century economy, NYU Law has added five of the country’s most active and sought-after IP academics to its faculty during the past five years. Beebe and Strandburg joined in 2009, followed by Jeanne Fromer in 2012 and Christopher Sprigman and Jason Schultz in 2013. They all join Rochelle Dreyfuss, who has been a faculty member and IP stalwart since 1983.

“NYU Law has assembled an amazing group in IP in just a few years,” says Mark Lemley, a Stanford Law School IP professor and a founding partner of the complex civil litigation firm Durie Tangri in San Francisco. “It is arguably one of the best.”

While the six IP professors focus on different (though often overlapping) areas, one question they all explore is what best drives innovation—the primary reason for having laws that create intellectual property rights. Along with other full-time faculty members and adjunct professors, they offer nearly 30 intellectual property courses a year, including core and advanced courses in patents, copyright, and trademarks. The professors’ scholarship has had a major impact on the subject matter, including Dreyfuss’s analyses on changing patent law; Strandburg’s studies of cultural behavior to understand innovation; and Beebe’s groundbreaking paper examining trademark law as the new sumptuary code.

The other professors have also made early marks in the field, including Fromer’s examination of the proper audience for IP infringement and Sprigman’s book The Knockoff Economy: How Imitation Sparks Innovation (2012), which suggests that copying in creative areas, such as fashion, promotes rather than harms innovation. Schultz, who founded NYU Law’s Technology Law and Policy Clinic, is known for having developed a top-notch clinic at Berkeley and for generating innovative strategies for updating law and policy to serve citizens in the digital revolution.

An expert in copyright protections and their expansion, Diane Zimmerman, an award-winning former reporter for Newsweek and the New York Daily News, is now Samuel Tilden Professor of Law Emerita and continues to make significant contributions to the intellectual life of the group.

Because IP law so often overlaps with greater issues of culture and business, it also draws in faculty with non-IP specializations, such as Emily Kempin Professor of Law Amy Adler, who teaches art law and has weighed in on moral rights. Practitioners also teach various electives in particularly IP-heavy fields, including biotechnology, fashion, and entertainment. And, with the constant crossover between competition law and IP, including whether patent settlements that delay the release of generic drugs are illegally anti-competitive, antitrust professors Harry First, former chief of the Antitrust Bureau of the New York State Attorney General’s Office, and Eleanor Fox ’61, an expert in global antitrust issues, also play a role in the curriculum.

All this activity adds up to what Sprigman describes as an “invigorating” academic environment where endless sparks generate ideas and an unparalleled group of colleagues helps develop them.

[SIDEBAR: A Founding Father of IP]

PATENTS

Patents protect original inventions on everything from car parts to prescription drug formulas to plastic bracelets on the arms of elementary-schoolers. Patents must be applied for and approved, and the owner of a patent has the exclusive right to use his or her invention. That means if a company wants to sell a product that would use another’s patented property, it must either pay the owner for a license or risk being sued.

Many patent law practitioners and experts, including Dreyfuss and Strandburg, have technical or scientific backgrounds in areas such as physics or engineering. So while patent litigation might have gone mainstream, courts continue to struggle with the theoretical question of which inventions are and aren’t eligible for patent protection—and should and shouldn’t be. Both professors’ work delves into the issue of patentability, using empirical research to develop theories on the broad question of what levels of protection will lead to the most innovation.

Many patent law practitioners and experts, including Dreyfuss and Strandburg, have technical or scientific backgrounds in areas such as physics or engineering. So while patent litigation might have gone mainstream, courts continue to struggle with the theoretical question of which inventions are and aren’t eligible for patent protection—and should and shouldn’t be. Both professors’ work delves into the issue of patentability, using empirical research to develop theories on the broad question of what levels of protection will lead to the most innovation.

When Dreyfuss, Pauline Newman Professor of Law, first joined NYU Law, she had planned to focus on civil procedure. But when longtime NYU professor and renowned copyright expert Alan Latman became ill, she was asked to teach a patent law course as well. Latman helped Dreyfuss get up to speed and even to develop her first research paper on patents. Over the course of her more-than-30-year career in academia, Dreyfuss has produced a vast array of scholarship that has made her sought-after by governments from Russia to China seeking to improve their own patent systems.

Dreyfuss also has a reputation for practical scholarship on domestic patent law issues. “Her work is very appreciated not only by intellectual property scholars but also by judges, which is unfortunately rare in the legal academy,” says Jane Ginsburg, a Columbia Law School IP professor and a frequent collaborator with Dreyfuss. Ginsburg also cited Dreyfuss’s deep knowledge of the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.

About the time she began focusing on IP, Dreyfuss says, patent law “happened to get hot” following the 1982 founding of the Federal Circuit, unique among the appeals courts in that it has sole jurisdiction over most patent appeals and was created to allow the development of unified patent law.

When the Federal Circuit celebrated its five-year anniversary, Dreyfuss was asked to write a paper evaluating the court on its then-short history. She has repeated that analysis on several anniversaries since and jokingly advises her students to be careful what they write about, lest they be doing it for 30 years.

These days, Dreyfuss, who has a master’s degree in chemistry and worked as a research chemist at the company that is now Novartis before becoming a lawyer, is particularly interested in patent law as it relates to life sciences and pharmaceuticals.

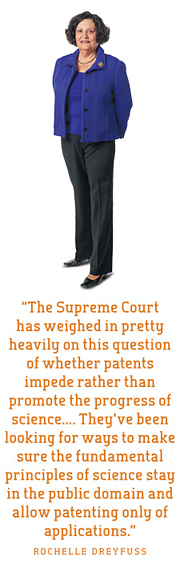

Cases in that arena, addressing questions such as whether human genes can be patented and whether drug patent owners can strike deals with generic drugmakers to maintain market exclusivity, have been subjects of focus at the nation’s highest court. “The Supreme Court has weighed in pretty heavily on this question of whether patents impede rather than promote the progress of science,” says Dreyfuss. “They’ve been looking for ways to make sure the fundamental principles of science stay in the public domain and to allow patenting only of applications.”

Dreyfuss has continually advocated for a patent system that allows progress in scientific research without taking away developers’ incentives to innovate. She served on an advisory committee for the secretary of health and human services on genetics, health, and society, which issued a report on how gene patents and licensing practices affect patients’ access to genetic testing. Dreyfuss argues that enterprises that offer gene-based testing should receive protections from patent infringement claims and that those conducting research on genes should be granted exemptions from infringement. Such exemptions remain a hot topic in the patent world.

Dreyfuss has continually advocated for a patent system that allows progress in scientific research without taking away developers’ incentives to innovate. She served on an advisory committee for the secretary of health and human services on genetics, health, and society, which issued a report on how gene patents and licensing practices affect patients’ access to genetic testing. Dreyfuss argues that enterprises that offer gene-based testing should receive protections from patent infringement claims and that those conducting research on genes should be granted exemptions from infringement. Such exemptions remain a hot topic in the patent world.

Strandburg, who has a PhD in physics, seeks answers to the more theoretical questions of IP law in an effort to understand how the patent system could best work to promote scientific and technological progress. In recent years, she has conducted research studies of what she calls “knowledge commons,” broadly defined as any group that collaboratively shares knowledge or information with the purpose of creating and innovating. Strandburg and her fellow researchers, including standout student Can Cui ’12, now an associate in the Hong Kong office of Morrison & Foerster, have looked at groups ranging from news gatherers to surgeons to roller derby teams. Strandburg’s book Governing Knowledge Commons (2014), co-authored with Brett Frischmann of Cardozo Law School and Michael Madison of the University of Pittsburgh School of Law, examines how each of those groups innovate and whether they do so without seeking or being able to seek formal patent protection.

For instance, in an evaluation of doctors who, under the auspices of the National Institutes of Health, are researching rare diseases that affect children, Strandburg and her collaborators discovered that the researchers worked together and shared data with apparently little concern about which of them could patent what. Patents may be of increasing concern later, Strandburg says, as the research teams interact with pharmaceutical companies to develop treatments based on their research.

In other research, Strandburg addresses how much patent protection is necessary to spur innovation. Though Strandburg says more research is necessary to reach any final conclusions, empirical research she and others have done leads her to believe that the question of what is patentable should depend not only on the details of the particular invention but also on whether there is a community that will innovate regardless of whether patents are available. In other words, where patent protection is unnecessary to spur innovation, perhaps the law should take that into account and consider limiting the availability of patent protection for those areas.

COPYRIGHT

Unlike a patent, which must be applied for, anyone who writes an original song or creates a new painting is eligible for copyright protection. Whether a photograph that incorporates part of another’s painting is “transformative” enough not to violate the earlier work’s copyright, or whether a website’s use of a news organization’s reporting or imagery is “fair use” are common questions being hammered out in court.

Addressing themes similar to those explored by Dreyfuss and Strandburg, Fromer and Sprigman have identified the broader pressing issue in copyright cases as whether the assumptions on which IP law is built—that protection is required to promote creativity and innovation—are actually true.

Landmark Supreme Court decisions—such as the 1994 ruling in favor of rap group 2 Live Crew over its use of Roy Orbison’s “Pretty Woman” lyrics—and new litigation—like the 2013 Second Circuit decision for the artist Richard Prince concerning fair use, or the battle between Robin Thicke and Marvin Gaye’s estate over Thicke’s 2013 summer hit “Blurred Lines”—make it easy to grab copyright students’ attention, Fromer says.

Fromer splits her time fairly evenly between copyright and patents. She is attracted to the fact that the two systems—both designed to protect inventors and promote innovation—look so different.

Fromer splits her time fairly evenly between copyright and patents. She is attracted to the fact that the two systems—both designed to protect inventors and promote innovation—look so different.

Fromer compared the two in a paper published this year and co-authored with Stanford’s Lemley. The professors examined copyright and patent case law, noting that, in some copyright cases, the audience used to determine infringement is a mix of the so-called ordinary observer and experts in the relevant field.

In patent cases, on the other hand, whether a person’s patent has been infringed is often judged only from the perspective of experts.

Copyright and patent protection exist, Fromer says, to provide incentives for people to create valuable things, and the general idea is that people will cease creating if they can’t recover their investments of time or money. Therefore, if the copy doesn’t harm the creator in the marketplace, she says, “there’s no reason to care because it shouldn’t be diminishing their incentive to create.”

For that reason, patent lawyers, judges, and scholars can learn from copyright cases that ask both whether a consumer would have substituted the copy for the original and what is original about the work the party is looking to protect, Fromer says.

Fromer is also working on a research project with Sprigman that seeks to evaluate what drives creativity and, in turn, what sort of formal intellectual property protection is necessary to develop incentives for continued creativity.

Such empirical work is important, says Sprigman, “because for too long, a lot of intellectual property protection has been a faith-based enterprise. That is really changing. There is a real turn in the scholarship toward trying to understand at a pretty basic level how the mechanism does or doesn’t work.”

Sprigman and Fromer’s project, done in partnership with Christopher Buccafusco of the Illinois Institute of Technology Chicago-Kent College of Law and Zachary Burns, a postdoctoral fellow at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University, involves asking volunteers to complete tasks that require creativity. One group is told that anyone who completes the task will be eligible for a $1,000 drawing but that those who do it best will receive more tickets. Another group is told that only those who are best at the tasks will get tickets. The purpose of the study, which they plan to complete in 2014, is to gauge whether participants are encouraged to be more creative when they’re eligible for a reward no matter what, or if they’re more creative if they have to meet some sort of threshold of creativity to be eligible. The results will suggest whether requiring a threshold level of achievement to receive copyright protection—as is required to receive a patent—would lead to increased creativity.

Sprigman and Fromer’s project, done in partnership with Christopher Buccafusco of the Illinois Institute of Technology Chicago-Kent College of Law and Zachary Burns, a postdoctoral fellow at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University, involves asking volunteers to complete tasks that require creativity. One group is told that anyone who completes the task will be eligible for a $1,000 drawing but that those who do it best will receive more tickets. Another group is told that only those who are best at the tasks will get tickets. The purpose of the study, which they plan to complete in 2014, is to gauge whether participants are encouraged to be more creative when they’re eligible for a reward no matter what, or if they’re more creative if they have to meet some sort of threshold of creativity to be eligible. The results will suggest whether requiring a threshold level of achievement to receive copyright protection—as is required to receive a patent—would lead to increased creativity.

Another arm of Sprigman’s work involves analyzing creative areas, such as food, fashion, and open-source software, in which, for whatever reason, there is very little or no intellectual property protection. Some of that work was captured in The Knockoff Economy (2012), co-authored with University of California, Los Angeles law professor Kal Raustiala.

“The value of looking at low-IP industries is you learn something about how they get along in the absence or the partial absence of IP, and how they innovate. There are many ways to innovate and to capture the gains of innovation without relying necessarily on formal law,” Sprigman says. He points to stand-up comedy as an example. Comedians don’t rely on formal law, he says, but they’ve developed a system of community norms against joke stealing that they enforce against one another. (For more on Sprigman, see his faculty profile.)

Like all of their IP faculty colleagues, both Sprigman and Fromer are also closely watching cases in which innovation, and how it pushes against intellectual property law, are playing out in court. One recent high-profile example is the so-called Google Books case, in which the Authors Guild sued the search giant over its plans to scan thousands of books and make them searchable for free online.

In a landmark decision, Second Circuit Judge Denny Chin, who heard the case at the district court level, ruled in November 2013 that Google’s project was fair use because it was transformative and contributed to the public good. The decision is currently on appeal.

Chin’s decision and a few other recent holdings “really shape the fair use analysis in favor of the defendants” and expand what “transformative” can mean in the analysis, Sprigman says. Whereas fair use is most commonly thought to be transforming the nature of the work, such as 2 Live Crew turning “Pretty Woman” into hip-hop, in the Google Books case the transformation was of the way the works would be used, in this case for research. The works themselves stayed the same.

Sprigman and Fromer’s colleague Jason Schultz was also closely watching the Google Books case. As it turned out, the judge was keeping an eye on Schultz’s thoughts on the subject of fair use. In his opinion, Chin repeatedly cited an amicus brief authored by Schultz and others on behalf of humanities and law scholars. The brief touted the positive impact the Google project would have on research including “data mining,” which involves searching large amounts of data to detect patterns.

“The significance of this case extends far beyond” Google’s book project, the Schultz amicus brief said. Allowing books to be searched on a mass scale has endless potential for research progress to benefit society, it continued, “and none of the works in question are being read by humans as they would be if sitting on the shelves of a library or bookstore.” Thus, the brief argued and Chin agreed, the project doesn’t infringe the authors’ rights or violate the ideals of copyright protection.

Schultz’s scholarship also addresses copyright’s “first sale” doctrine, which says that when someone purchases a copyrighted work, such as a book at a bookstore, it is then his to loan or sell as he pleases. How that doctrine works in the digital realm, where consumers download books or songs, is unsettled. “If we don’t find a way for consumers to maintain a personal property interest in digital media, it will leave the copyright system out of balance,” Schultz says, because purchasers will have less incentive to buy copyrighted works and instead might download them illegally.

Schultz’s scholarship also addresses copyright’s “first sale” doctrine, which says that when someone purchases a copyrighted work, such as a book at a bookstore, it is then his to loan or sell as he pleases. How that doctrine works in the digital realm, where consumers download books or songs, is unsettled. “If we don’t find a way for consumers to maintain a personal property interest in digital media, it will leave the copyright system out of balance,” Schultz says, because purchasers will have less incentive to buy copyrighted works and instead might download them illegally.

In a forthcoming paper with Case Western Reserve University School of Law’s Aaron Perzanowski, Schultz argues that any new law drafted on the topic should simply say that whether the copyrighted work is in digital or analog form, the consumer owns it and has the right to resell it. “If you drafted a law that says those things, you’d win in the digital age,” he says.

As a professor of clinical law, Schultz works with students on what he calls the “big policy issues.” Students in his Spring 2014 clinic submitted two amicus briefs to the Supreme Court. In the high-profile patent case Alice v. CLS Bank, the students argued that abstract patents are particularly problematic in the software realm because they encourage frivolous litigation and prompt businesses to create large patent portfolios for the sole purpose of defending against such suits. The students also filed a brief in ABC v. Aereo on behalf of smaller broadcasters in support of streaming Internet television service Aereo. The startup charges users a small monthly fee to watch local programming on their computers or mobile devices—the same local programming that could be watched for free on a TV with rabbit ears, Aereo argued. The US Supreme Court sided with ABC and other major broadcasters in June, however, ruling that Aereo infringed on their copyrights.

The main focus of students’ projects, Schultz says, will be to advocate protection of the public interest. Spring 2014 students advised the New York Public Library system on how to best make available to other libraries and institutions the software it is developing to make library works more digitally accessible. Some students also were placed at the ACLU under the supervision of ACLU attorneys Catherine Crump and Ben Wizner ’00, director of the ACLU’s Project on Speech, Privacy, and Technology. The students evaluated and made recommendations to criminal defense lawyers on how to defend against law enforcement’s use of individuals’ cell phone location data, and drafted model pleadings to be used by these lawyers in requesting such cell-related information from the government.

“There is no end to the kinds of projects that students can work on that really make a contribution” to IP law, Schultz says of his clinic.

Amanda Levendowski ’14, a clinic student who will join Cooley this fall as an associate, said she found working in the not-for-profit environment invaluable. Schultz was instructive, she said, on how she can integrate that type of service into her work at the law firm.

TRADEMARK

The third prong of intellectual property, trademark, involves the various tools, including logos, words, symbols, and colors, that companies use to identify their products. Trademark law allows companies to seek damages from those who try to sell knockoff products or trade on their brands by confusing consumers into thinking they’re buying a product that was made by another, usually inferior, company.

Despite its undisputed relevance in the business world, trademark law has historically received less academic attention than patents and copyright law. That hole in intellectual property scholarship led Barton Beebe to develop his expertise in trademark law.

“When I really started reading [about trademark law], I thought it was the lens through which you can see the rest of the universe. Everything was there—economy, culture, politics, expression,” says Beebe, who has a PhD in English, including work in cultural studies. And yet, he says, it seemed that it was under-theorized and understudied.

Beebe’s research—and his interpretations of trademark’s broad reach—allows NYU to be one of the few law schools that offer an advanced course in trademark law, though that’s something Beebe expects will change soon. “It’s becoming obvious that [trademark law] is so wrapped up with the state of the 21st-century economy,” he says, especially as branding becomes more important in global commercial centers like New York, Tokyo, Paris, and, increasingly, Silicon Valley.

Beebe’s research—and his interpretations of trademark’s broad reach—allows NYU to be one of the few law schools that offer an advanced course in trademark law, though that’s something Beebe expects will change soon. “It’s becoming obvious that [trademark law] is so wrapped up with the state of the 21st-century economy,” he says, especially as branding becomes more important in global commercial centers like New York, Tokyo, Paris, and, increasingly, Silicon Valley.

Adjunct Professor David Bernstein, a partner at Debevoise & Plimpton, teaches the advanced class with Beebe. Bernstein is a renowned trademark lawyer who defended luxury company Yves Saint Laurent (YSL) against allegations it violated a mark owned by high-priced shoemaker Christian Louboutin. In a landmark 2012 decision, the Second Circuit allowed Louboutin to keep its trademark on red soles but said YSL could continue to sell its all-red shoes.

Bernstein has known Beebe since the latter’s law school days, when Beebe was a “star” summer associate at Debevoise, Bernstein says. Today, Beebe is more widely known as a standout for his groundbreaking 2010 Harvard Law Review paper “Intellectual Property Law and the Sumptuary Code,” which compared trademarks to laws that restrain luxury and extravagance for the purpose of enforcing social hierarchies.

“I’m obsessed with how trademark law facilitates status distinctions in society—not necessarily hierarchical distinctions in terms of status distinctions, but also how trademark law helps facilitate horizontal distinctions in a mass culture. It’s as if in a mass capitalist democracy, if we didn’t have trademark law, we’d have to invent it,” he says.

People buy signs, which include branded clothing and products, Beebe continues, to distinguish themselves from others. “If you don’t have religious or ethnic identity, if you live in a massive, multicultural, globalized city…people rely more on trademarks and brands. And trademark law is the regulation of that distinction.”

Trademark law protects the world’s most recognizable brands—such as Coca-Cola or Nike—from “dilution” of their marks by allowing them to sue those whose products might reflect badly on their brands, even if no consumer would think the major brand-owner actually made the product. “What’s interesting about anti-dilution protection, and IP law in general, is that trademark law is increasingly designed to protect the strong more than the weak,” Beebe says.

One wonders to what extent IP law is following the increasingly large divide between society’s rich and poor, he says. “Anti-dilution law is a really obvious expression of the 1 percent,” Beebe adds, since only the most famous trademarks qualify for such protection.

MOVING FORWARD

Beebe’s analysis of trademark law’s representation in greater society goes part and parcel with his fellow faculty members’ continued evaluation of how IP laws should mold and change to best contribute to society. They are all eager to use available case law and their own empirical research to contribute to that conversation.

Spring 2014 represented the first time all six professors were on campus together, and it brought not only expanded course offerings but also new life to the school’s Engelberg Center on Innovation Law and Policy.

The center is unique at NYU Law in that all full-time IP professors serve as faculty co-directors. The center pursues a mission to foster interdisciplinary work in the area of innovation and law, and to bring in top-notch IP practitioners and experts to interact with faculty and students.

To that end, the center held an array of events that attracted a wide spectrum of audiences, including “Taking on the Take- Down Notice: Copyright, Youth and Educators in Harmony,” which featured a panel of media-savvy New York high school, college, and graduate students, and “Drones and Aerial Robotics,” which drew together aerial photographers, former military personnel, privacy wonks, and robotics enthusiasts.

In celebration of the Engelberg Center’s 20th anniversary this year, the IP faculty took part in substantive panels on IP topics with NYU Law trustees and guests such as US Supreme Court Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sonia Sotomayor.

The center is launching an Empirical Innovation Law & Policy Research Initiative this fall that will focus on the data-driven study of the interplay between law, policy, and innovation. It will kick off in October with a two-day conference on Empirical Scholarship in Intellectual Property: New Evidence Relevant to Policy.

In September, the center will host the 2nd Thematic Conference on Knowledge Commons Governing Pooled Knowledge Resources. Organized by Strandburg, the event aims to take stock of the latest developments in the interdisciplinary study of knowledge commons, and will seek to better understand how knowledge commons work, where they come from, what contributes to their durability and effectiveness, and what undermines them. The conference will pay special attention to knowledge commons in the fields of medicine and the environment.

What stands out about these faculty is how invested and excited each is in the others’ works. It is a cohesive group that also benefits from a diverse set of interests. That allows the center to approach analysis of innovation law and policy from many angles.

Each of his new colleagues, Sprigman says, “has done more than one thing in their career that has changed the way people think” about an IP question. They are the people who have driven him throughout his legal career, he says, “and now I’m hanging out with them.”

—Erin Geiger Smith is a freelance journalist in New York City. A former legal reporter at Reuters, she has written for the Wall Street Journal and the Daily Beast, among other outlets.

—