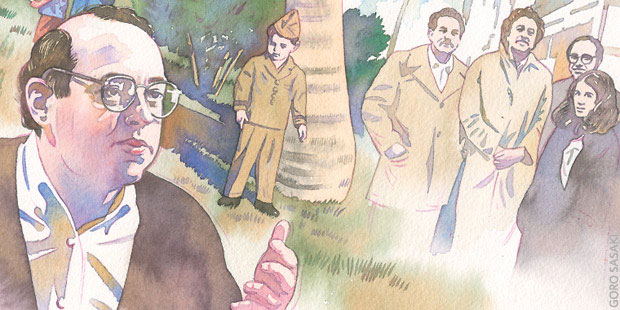

Creative Counsel

Burt Neuborne is a litigating academic, a pragmatic liberal, and an inquisitive teacher. He sees himself, simply, as an imaginative lawyer.

Printer Friendly VersionTo understand how Burt Neuborne has managed to win so many watershed constitutional cases and harvest billions of dollars for families of Holocaust survivors around the world, all while being a faculty star at the New York University School of Law, it helps to reach back to his days as a gangly youngster on the postwar streets of Jamaica, Queens. As dusk would fall, young Burt would be out playing stickball with the rest of the neighborhood kids and the receding light would make the spaldeen (as the pink Spalding rubber ball was known) hard to pick out. His less relentless buddies were ready to call it a day. Not Neuborne.

“When it would get dark and I was losing, I would always say, ‘We can play another inning’,” he remembers.

Now fast-forward to the Vietnam War era to roughly 1970, when Neuborne, a lawyer for the New York Civil Liberties Union, was defending an artist who had been arrested for sewing a 7 1/2 foot-long American flag into the shape of a penis, stuffing it, and displaying it near the window of a Madison Avenue gallery. A three-judge criminal court panel convicted the artist of desecrating the flag and a seven-judge New York State Court of Appeals affirmed that ruling. But displaying his legendary doggedness, Neuborne twice took the case all the way to the United States Supreme Court and eventually got a lower court federal judge—the 37th judge to rule on the matter—to declare the flag-desecration statute in violation of the First Amendment’s right of free speech. Exhausted prosecutors called it a day, and Neuborne had won the game in extra innings.

It’s 1973, and this time, in a more momentous case, Neuborne displayed even more fevered persistence. Now assistant legal director at the American Civil Liberties Union, he was defending American bomber pilots in Thailand who were facing courts-martial for refusing to carpet-bomb Cambodia. To Neuborne’s astonishment, Federal Judge Orrin Judd of the Eastern District in New York upheld his argument—that the pilots could not be punished since Congress had not authorized the war. But the Second Circuit Court of Appeals stayed Judd’s ruling, allowing the bombing to continue. It was summer, so Neuborne could not appeal to the full Supreme Court, and the circuit justice, Thurgood Marshall, despite his anguished personal misgivings, declined to step in. But Neuborne knew that there was at least one more inning he could play.

The ACLU had a “Douglas watch” to keep tabs on the whereabouts of the Court’s most liberal jurist, Justice William O. Douglas, whenever capital punishment and other irreparable-harm cases required emergency stays. Neuborne flew to Washington State, where Douglas was vacationing, and, in a scene evocative of Henry IV’s humbling call at Canossa in 1077, he knocked one morning on the door of Douglas’s rustic cabin in Goose Prairie. Douglas, unfazed, agreed to hear oral arguments in the Yakima post office.

Douglas, as Neuborne recalls it, was frail and tired at the end of his career. “People sort of knew this was his last hurrah.” The canny Douglas found a sly way of warning Neuborne not to be too hopeful, that even his blessing could be futile. “Mr. Neuborne,” the judge asked, “what happened when I was asked to intercede 20 years ago?”

Neuborne remembered that Julius and Ethel Rosenberg had been executed in 1953, for spying, a step taken after the full Supreme Court overruled a Douglas stay. But Douglas’s pessimism didn’t dissuade Neuborne. He anticipated that this time there would not be enough justices lingering in the steamy capital to overrule Douglas.

Douglas indeed ruled in his favor. But the next day the Supreme Court held a conference call to reinstitute the stay. Yet it never heard the case on its merits. The Nixon administration, figuring that a Supreme Court hearing might jeopardize its Cambodia policy, simply arranged to have all the pilots honorably discharged. From Neuborne’s point of view, playing after the sun went down paid off once more.

“I verge on the obsessive,” Neuborne said, recalling this episode. “My wife has a wonderful quote from Santayana that she adapted: ‘My husband is a man who redoubles his efforts once he loses sight of his goals.’ ”

For a man who supposedly loses sight of his goals, Neuborne, 63 years old, has managed to carve out a life that has been elegantly coherent—of pioneering litigation, teaching, and scholarship that has revolved around a few signature themes like the First Amendment and civil rights. He has argued cases six times before the Supreme Court and briefed some 200 others. His imprint on civil-liberties laws and his ability to analyze the pertinent issues has made him the go-to guy over the years for dozens of journalists and scholars seeking insights on those laws. He shows no signs of slowing down, either. During the last year or so, Neuborne was a key player in two of the seminal cases of our time.

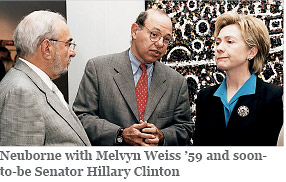

He helped defend the groundbreaking McCain-Feingold campaign-finance reforms, advising the bill’s sponsors throughout the process—even helping to craft the legislation. Neuborne also has been deeply immersed in two major Holocaust cases. He is plaintiffs’ counsel in a lawsuit against Swiss banks over their handling of Nazi-era bank accounts and was the principal lawyer in a series of Holocaust suits involving compensation for slave laborers of wartime German industry.

Yet, for the past three decades, the chief institutional anchor of his life has been not an opulent law office but a podium at the New York University School of Law, where he started teaching in 1972 as an adjunct and now has the title of John Norton Pomeroy Professor of Law. There he also serves as the legal director of the Brennan Center for Justice, which was started in 1995 by Supreme Court Justice William J. Brennan’s family with a broad mission of trying to clear the hurdles to a more democratic society. The center’s most notable Supreme Court victories have been its successful defense of the McCain-Feingold campaignfinance reform bill, where Neuborne wrote the brief, and Velazquez v. Legal Services Corp., where Neuborne briefed and argued a landmark First Amendment challenge to the government’s effort to muzzle lawyers for the poor. While juggling these enormously important cases, Neuborne has consistently prepared and inspired NYU School of Law students with his lively Evidence and Procedure lectures.

Yet, for the past three decades, the chief institutional anchor of his life has been not an opulent law office but a podium at the New York University School of Law, where he started teaching in 1972 as an adjunct and now has the title of John Norton Pomeroy Professor of Law. There he also serves as the legal director of the Brennan Center for Justice, which was started in 1995 by Supreme Court Justice William J. Brennan’s family with a broad mission of trying to clear the hurdles to a more democratic society. The center’s most notable Supreme Court victories have been its successful defense of the McCain-Feingold campaignfinance reform bill, where Neuborne wrote the brief, and Velazquez v. Legal Services Corp., where Neuborne briefed and argued a landmark First Amendment challenge to the government’s effort to muzzle lawyers for the poor. While juggling these enormously important cases, Neuborne has consistently prepared and inspired NYU School of Law students with his lively Evidence and Procedure lectures.

“Burt has tremendous energy,” said Judge Edward R. Korman of Federal Court in Brooklyn, who decided how to distribute the money in the settlement of the Swiss banks case. “While everything’s going on he sends me law review articles he’s written, he’s speaking in various places, he’s filing papers in this lawsuit, and in the German lawsuit. I asked him a couple of weeks ago if he was on steroids. He’s absolutely brilliant.”

Neuborne has the balding, bespectacled look of a stereotypical scholar, but his face is leavened by the kind of chipmunk cheeks that a mother loves to pinch and the springing steps of a long-distance runner who has completed two marathons (New York and Paris) and still jogs five miles a day on the treadmill. His speech has a slight New York inflection and his voice something of a Mel Brooks rasp, yet he has an impressive Professor Higgins-like gift for well-parsed sentences. Any formality, though, is lightened by a ready smile and a puckish sense of humor.

All of these attributes are evidently arrows in his instructional quiver, qualities that in 1990 won him the University’s Distinguished Teacher award—almost never given to teachers who confront large lecture classes of 100 or more, as he usually does. “I’m an unreconstructed ham,” he said. “That’s why I love being in court, that’s why I love teaching. I love the performance, the standing up in front of a group and performing for them. But I also love the intellectual challenge of it. There’s something splendid about seeing the material each year through the eyes of an idealistic and smart student who asks hard questions about it.”

It may seem paradoxical, but as a professor Neuborne has generally avoided the topics that have earned him his legal stripes. He spurns courses on the First Amendment or affirmative action or women’s rights, topics that as he puts it are “close to my politics.” Rather, he teaches workhorse courses in Evidence.

“If I were to teach affirmative action I’d have to be careful not to teach it as a cheerleader,” he explains. “If you’re going to be a teacher and not a cheerleader you have to force students to confront, to realize there are reasonable arguments that can go the other way and force students to develop those arguments. And I can do it. But it’s not something I try to do.”

Indeed, when he does teach a rare constitutional law class he will often take a contrarian position by, say, advocating censorship. “I force them to argue me off of the position they know I don’t agree with,” he said. “The purpose of the classroom is to exercise their minds, not to find out what I think.” He has learned, he said, that “the students have absolutely no fear of me and chase me around the classroom.”

A visit to a run-of-the-mill Evidence class in March, when students were just back from their spring break, makes palpable Neuborne’s zest as a teacher. Neuborne clips a small microphone to his gray V-necked sweater and spends the first 15 minutes of the two-hour class reacquainting students with the differences between statements made assertively and those made more obliquely or through behavior (an opened umbrella declares it’s raining, for example). At trial, it’s the nonassertive statements that can avoid being classified as hearsay. As he talks, Neuborne’s voice rises to a singsong. The students seem riveted.

“He’s the best,” said Lauren Smith (’04), who shopped around for teachers by auditing classes. “He’s very clear and he has a kindness and a sense of humor that comes through in every lecture. He does a good job of mixing the practical and the theoretical, which not all professors do.”

[SIDEBAR: Neuborne Goes Hollywood]

When you ask Neuborne what he likes about teaching, he quotes John Sexton, who was dean of the Law School between 1988 and 2002 before becoming University president. “Sexton used to say when you became a teacher you were blessed because you entered into cyclical time instead of linear time. Everything starts fresh all the time. Each new year is a new beginning. This is at least the twentieth time I’ve taught Evidence and the novelty is still there. I learn something new every year.”

Neuborne tells of modeling himself on Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who was head of the women’s rights project at the ACLU at the same time she was a professor at Columbia Law School, arguing six cases before the Supreme Court that changed the way the law treats gender. “I watched how a superb academic could also be a remarkably effective litigator and actually change things,” he said. His teaching, he said, is always enhanced by his work as a lawyer. “I’m a good, strong teacher, but I don’t think I could be anything like the force I can be in the classroom if I were teaching just abstractions or my reading of what other people did. The fact that I actually do this stuff is what gives me confidence.”

Three or four times a year Neuborne moderates a panel of lawyers and other experts in a role-playing exercise on a controversial issue. In February he ran an Anti-Defamation League-sponsored panel at the Law School on how to handle anti-Semitism on campus. The panel included Tom Gerety, a former president of Amherst who is now the executive director of the Brennan Center, and S. Andrew Schaffer, general counsel of New York University. Neuborne had the panelists pretend they were students, deans, college presidents, journalists, lawyers, and judges handling a mock case where a campus newspaper prints a cartoon of Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon in an SS uniform with a caption: “Stop Israeli Nazi Apartheid.”

The mock case raised questions about the parameters of free speech, and as he prowled the stage, Neuborne ratcheted the issue up, probing whether hateful speech can be so extreme that it can incite readers or listeners to violence, discussing differences in speech made on public or private college campuses, asking whether it matters if the offensive newspaper is distributed publicly or on the doorsteps of Jewish students, and considering whether it matters if the president is Jewish or not.

Neuborne certainly doesn’t shrink from controversy. The class-action lawsuit against Swiss banks, aside from being astonishingly complicated—some legal papers had to be translated into 16 languages, for example—has also rankled some interested parties. The suit settled for $1.25 billion, almost $700 million of which already has been distributed to descendants of bank account holders, inmates of slave-labor camps financed by Swiss banks, refugees who were turned away from Switzerland, and people whose assets were looted by the Nazis and fenced through Swiss banks. A few American survivors or spokesmen like lawyers Thane Rosenbaum and Samuel J. Dubbin have assailed the settlement for giving the bulk of the looted-assets money to survivors in the former Soviet Union and leaving only a small percentage for U.S. survivors. In an interview, Neuborne (who took on this case pro bono) contended that the needs of elderly American survivors, protected by this country’s social safety net, were not as profound as those of 135,000 elderly Soviet survivors, who lack such basics as food, winter fuel, and emergency medical care.

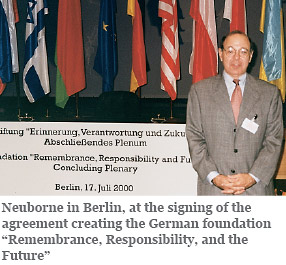

As if that case were not consuming enough, Neuborne also was a principal counsel representing slave laborers owed money by German industry and then became one of two U.S. trustees of the German Foundation, which is now distributing the $5.2 billion in compensation. Both Holocaust cases involved many flights to and from Europe, and Neuborne admitted in a conversation last February that he was tired and “very rundown.”

How does he conduct two or three careers at once—lawyer, teacher, writer? Neuborne self-effacingly credits the help of his Brennan Center research assistants and the computer access arranged for him by NYU through which he can connect to relevant databases anywhere in the world. But he also admits that he permits his work to occupy much of what, to another human being, would be free time.

“I work all the time,” he said. “I cannot remember a weekend I haven’t worked a very substantial part of the weekend. When I’m working on a case that I care deeply about it’s the closest thing to me to being creative. I would have given anything in my life to be a writer or a painter, but the talent that was given to me was to be an imaginative lawyer—and I put that imagination at the service of issues I care deeply about.”

Even when supposedly relaxing at their summer house in the Hamptons, he and Helen Redleaf Neuborne, his wife of 42 years who is now a senior program officer at the Ford Foundation specializing in poverty work, have what they call “study dates.” They will sit in the same room with a fire going and take out their laptops. “And we’ll be very happy,” he said. “We spend four or five hours together, close the computer, go out to dinner and feel terrific.”

He has been able to continue working this hard despite open-heart surgery in 2002 and a tragedy that has cast a shadow over his autumnal years. Lauren, one of his two daughters and a rabbinical student at Hebrew Union College, died suddenly in 1996 at the age of 27. She had a heart condition that required a pacemaker and a misfiring brought on a massive heart shock. For months afterward Neuborne walked the streets of Greenwich Village, crying. Friends told him to take the Holocaust cases to find something to animate him again, and it was more than a coincidence that those cases connected him to his daughter’s interest in Judaism. “The reason friends urged me to take this was I was in despair, I was just in despair,” he said.

Neuborne’s older daughter, Ellen, her husband, David Landis, and two children, Henry, 9, and Leslie, 5, moved from Washington to New York to be near him. “That has been a salvation,” he said.

The first of four children, Neuborne was born in the Riverdale section of the Bronx on New Year’s Day, 1941, an event he likes to view with a dose of wit. “Even then I was a bad tax planner,” he said. “I deprived my father of his tax exemption for 1940.” His family soon moved to Greenpoint, Brooklyn, and moved again when he was four years old to Queens.

Young Neuborne was close to his maternal grandfather, Louis Danovitch, an immigrant from Odessa, Ukraine, who taught him how to read the stock tables and gave him a taste for intellectual seriousness. He also gave Neuborne’s father, Sam, a tailor, a job managing his sportclothes factory loft.

Sam, who died five years ago, was clearly the strongest influence in Neuborne’s life. He was the kind of principled individual who after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki returned his war medals to the Pentagon. But he was also a more interesting puzzle, a political leftist who at the same time was a crack swimmer and Navy frogman—an underwater demolition specialist—during World War II. In fact, he had a front-row seat at the D-Day invasion, having been sent into Omaha Beach hours before the actual invasion to blow up the spikes Germans had planted underwater to tear the bottoms out of Allied landing craft. Later, he visited a liberated concentration camp and returned from Europe telling Burt that he would “never set foot on the continent of Europe again.” During the war, Neuborne’s mother, Sylvia, promised that when his father returned he would take Burt to a Major League baseball game. But when the chance came his father declined. “We can’t go to a baseball game because they won’t let black people play,” he told his son. “We don’t support that.” But Burt remembers fondly that his father did take him to see a Negro League game between the Homestead Grays and the Cuban X-Giants.

Though his dad believed religion did more harm than good, Burt remembers being bar-mitzvahed in a storefront Conservative synagogue as “an affirmation of the right of Jews to continue to exist.” Whatever his political sympathies, he read a wide assortment of writers; some of Neuborne’s most indelible memories are of reading Dos Passos, Steinbeck, Hemingway, and Dreiser with his father. Today, Neuborne’s taste in books ranges widely, from Gabriel Garcia Marquez to Seamus Heaney to Anthony Trollope. “Till he died there was always a book the two of us were reading together,” Neuborne said of his dad. “He also got huge pleasure out of my academic career—when I became a teacher it was a fulfillment of his wish.”

His mother, Sylvia, spent her time caring for her home and giving her children a deep sense of affection. “If I had turned out to be a terrorist, my mother would sit on this couch and tell you that terrorism was the right thing to do,” Neuborne said. The feminist era did not deter her from her traditional convictions. Neuborne, whose wife, Helen, was the long-time executive director of the NOW (National Organization for Women) Legal Defense Fund, tells of once growing annoyed at seeing his mother fetching his father’s food and cutting it up at a wedding.

“I finally said to him, ‘You don’t have legs? You can’t get up and get your own food?’ ” Neuborne recalled. “ ‘Helen is going to kill you.’ ”

His mother shot back: “Shut up. I don’t need anybody to tell me I can’t get my husband’s food.” She died at 86 in 2001, and Neuborne thinks that the fact his father died two years before was not irrelevant. “There’s a price to having a great marriage,” he said. “You’re so fused with the other person you can’t exist without them.”

In his teens, despite the budding concern about the abuse of black civil rights and the excesses of the McCarthy era, Neuborne was not politically active. On Sundays, though, he would take an F-train to Washington Square Park to hear Allen Ginsberg and other Beat poets read at the fountain.

“I thought that was the center of the universe,” he recalled. “There were only two places—Washington Square Park and Paris. There’s a wonderful sense of closure that I really feel. When I was a boy, if you had told me that I would some day do what I do, I would say it is so far out of my reach that it is utterly incomprehensible. I walk through the park every night when I go home.”

His parents had wanted their only son, the first of his family to go to college, to be a doctor, so in 1957 he entered Cornell at age 16 as a pre-med. But by junior year, his mediocre science grades and physical clumsiness made him wonder if medicine was his calling. In a comparative anatomy class, he remembered, he reached for a dead shark specimen in a tank filled with formaldehyde. “I was so nervous and tense about being there that I fell into the formaldehyde. I stank for weeks. No matter what I did I couldn’t get the smell off.” In organic chemistry, he smashed a glass globe and splashed his eyes with sulfuric acid. “I thought, ‘Somebody’s trying to tell me something.’”

He finally told his parents that he couldn’t be a doctor, but that perhaps he would become a lawyer. “My father said, ‘Don’t be a lawyer, you’ll sell insurance for the rest of your life.’ In the Depression, the people he knew who went to law school wound up selling insurance.”

He chose law because it was an intellectual field that allowed you “to live like a gentleman”—comfortably but not lavishly. (He points out that he harbored such notions before “the Rolex years” of the 1980s, when the wave of mergers made lawyers wealthy and changed earning expectations.) He met his wife at Cornell; she was a sophomore and he was a junior who belonged to Tau Epsilon Phi. “We were the squarest pegs in the squarest holes,” he said. “My fraternity was the last fraternity to serenade a sorority.” And, though his contemporaries included fellow New Yorker Andrew Goodman and Cornell classmate Michael Schwerner, who went south to register voters and were slain and buried in Mississippi, Neuborne did not participate in the civil-rights movement in a fullthroated way.

Instead, he graduated in February 1961 and joined the Army Reserves, spending seven months at Fort Dix, where he was known as the “college idiot” because he couldn’t take his rifle apart. He then entered Harvard Law School while his wife, who had better grades and spoke three languages, went to work as a secretary to support him. “I loved Harvard,” Neuborne said. “It was a place of great intellectual excitement.”

He then joined a small Wall Street firm, Casey, Lane & Mittendorf, choosing tax work because, he confesses, that was the quickest route to a partnership. It was happenstance that brought him into civil liberties work—a lawyer in his Reserve unit was active in the NYCLU. Neuborne started doing briefs for the NYCLU at night and, by 1967, he realized he was “intrinsically out of place” in his day job. “I was uncomfortable spending all my energy defending very privileged people in ways that reinforced their privilege,” Neuborne said. (He took a leave of absence that the firm jokingly extended for 25 years.)

In those days, the NYCLU and ACLU were both located in a building in the Flatiron district honeycombed with left-wing organizations. Aryeh Neier was the NYCLU director. Ira Glasser was associate director. Ruth Bader Ginsburg was a director of the ACLU’s women’s rights project. “By the second day I knew this was what I was going to do,” said Neuborne.

The years between 1967 and 1973, when Neuborne served first as the NYCLU’s staff counsel and then as the ACLU’s assistant legal director, were heady times and Neuborne talks about them with brio. “It was the Vietnam era, the high point of the egalitarian revolutions, and you couldn’t lose. You threw something into court and you won. We used to sketch things out over lunch in the delicatessen. We developed something—I still remember writing it on the napkin—the enclave theory of constitutional justice. What we tried to do was to identify enclaves in American life from which the constitution had been shut out: prisons, schools, mental institutions, the military. The students’ rights cases came off of that napkin. The mental commitment cases. All of the cases dealing with free speech in the military.”

He is proudest of the cases that challenged the Vietnam War, because for a long time “they were existential cases: they couldn’t be won, but they had to be brought.” Neuborne also handled school desegregation cases, writing a Supreme Court amicus brief for the integration of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg, North Carolina, school system. There, too, his father’s influence made itself felt. Neuborne can never forget how as a 13-year-old in 1954 he traveled with his father on a business trip to Charleston, South Carolina, and there saw black-bordered newspapers announcing the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. His father happened to visit a local black minister that night and Neuborne remembers the jubilation.

“You have to look at Brown as a symbol,” he said. “It sent an enormously important message around the world that the law was not what Marx said. Marx said that law was a device to keep the weak in place, that the dominant economic class would use law as a club to prevent competition. Brown allowed the United States to compete in the Cold War with a different vision of law—that one could actually change the status quo on behalf of the poor and the weak. No one had ever thought about law that way. That set off a legal revolution in this country.”

It was in 1972 that he began teaching as an adjunct at NYU, and by 1974 he was asked to teach Evidence full time. The 20-hour workdays of the previous few years—the Vietnam War and civil rights cases and briefs flowing out of Nixon’s impeachment—helped spur his decision. So did his wife’s graduation in 1974 from Brooklyn Law School. Neuborne hoped that teaching law would allow him more time with his two young daughters while Helen launched her career as a Legal Aid lawyer for poor children. He took another leave of absence. “I didn’t tell them about my history of leaves,” he said.

Although he returned to the ACLU as national legal director from 1982-86, teaching became the center of his work life and has remained so.

“I love this place,” he said. “It has tolerated what is a quirky career. I don’t have a traditional academic career in that I don’t spend my time in my office writing law review articles. I actually go into court and try to put my ideas into practice. Very few schools would have tolerated that. I would have been told by many of my peers to make a choice.”

Neuborne has been fortunate that during his 30 years at NYU, the Law School has been on an upward spiral. The school acquired the pasta-making company C.F. Mueller in 1947, and in the late 1970s sold it for $115 million, netting a nice portion of the profit, even after the University got its share. The Law School’s administration wisely used the money to provide scholarships for top students, reward deserving faculty, improve its tuition subsidies and loan forgiveness program, and build more inviting housing. The fact that New York became a nicer place to live has not hurt. And NYU benefited by being among the very first law schools to be genuinely open to women.

“When five percent of the Harvard class was women, we were making it known in the 1970s that we were happy to have a 50-50 class,” Neuborne said. “We mined that vein of enormous talent of women who had missed the boat when it wasn’t possible for them to get into law school.”

Neuborne is not the reflexive liberal that he may appear to be, nor is he as convinced as he once was of the sweeping power of a legal decision that squares with his ideology. As a young lawyer, he was champing at the bit to challenge every wrong that came down the pike, but experience has taught him that even a favorable decision doesn’t always work out the way one hopes. Brown, he said, ended state-supported apartheid in many areas, but it also showed the limits of the law. “You can’t say that it successfully led to school integration,” he said. We’re still a society where by and large people are educated with their own race. It’s housing patterns that do it now. So Brown was a lesson about what law can’t do, the limits of the law.”

He also takes some nuanced views on more recent issues. In a conversation last winter just after the Massachusetts Supreme Court said that the state would have to marry gays equally with heterosexuals, Neuborne did not leap to praise the ruling. “I think I’m getting old,” he confided. “I think you must provide some form of relationship for gays that is identical to marriage—in terms of property and any kind of legal formulation. Whether you have to call it marriage is a different story. It may be that marriage has a religiously based connotation. Marriage was a sacrament before it was law. And the notion that the law will now turn marriage into something that historically it was not simply to achieve equality strikes me as at least problematic.”

Neuborne doesn’t look back with regret at not having built a career as a fulltime lawyer. The panel discussion on anti-Semitism drew powerful lawyers from Wall Street and midtown, yet Neuborne seemed completely in his element. “I’m certainly not intimidated,” he said. “My career as an academic has also included so much litigation, so much actual lawyering that I move very easily in that world. That’s a world where I think people respect me and I respect them. They know I know how to do what they do.”

His major regret, he said, is “the unwritten scholarship.” He has written perhaps 50 papers, and the piece he is proudest of was one in 1977 about “The Myth of Parity,” that business between federal and state courts shouldn’t be allocated randomly since each set of courts has certain advantages. But overall, he describes his scholarship as “adequate—I give it a B plus, not in quality, but in quantity.”

“For all my talk about being a litigating academic I still believe that the principal and irreducible responsibility of an academic is to produce scholarship,” he said. “Our major role is to comment critically on the world in which we live.”

“I question whether my litigation victories are more ephemeral than hard thinking would have been, and whether putting my energy into the production of serious thought would have changed things more than winning the lawsuits.” Still, such musings don’t diminish his retrospective savoring of his career as a law professor. “To be at NYU during the years I’ve been here,” he said, “is like being on a roller coaster that only goes up.”

—Joseph Berger has been a reporter at the New York Times for more than 20 years. Berger is also the author of Displaced Persons: Growing Up American After the Holocaust (2001).