What Price, Peace?

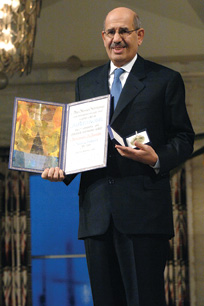

Nonproliferation treaties aren’t worth the paper they’re printed on unless someone holds signatory nations accountable; the head of the IAEA, Mohamed ElBaradei (LL.M. ’71, J.S.D. ’74), collects the dues.

Printer Friendly VersionIf one were to try to plot the point at the middle of the major international confrontations of the last few years, the result would probably be a spare, elegantly appointed room atop a curved high-rise building on the outskirts of Vienna. It is the office of Mohamed ElBaradei, the director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), and last March, ElBaradei spoke there about his efforts to direct the way to a peaceful settlement of the world’s most dangerous brewing conflict. “Everybody recognizes that Iran can only be resolved when all the concerned parties sit together, face to face, and have a negotiated settlement. There is no military solution,” he has long insisted, “even if you go through sanctions. An imposed solution is not a durable solution.” The world’s newest Nobel Peace Prize laureate has been frustrated with the Iranian government’s refusal to come clean about all of its nuclear activities and worried about the war drums that have beaten intermittently in Washington, especially earlier this year. There appears to be no doubt whatsoever in ElBaradei’s mind: “We have reached a point,” he says, “where there are no other options but diplomacy.”

With his oval-rimmed glasses, dark suit and trim moustache, ElBaradei, who earned an LL.M. in 1971 and a J.S.D. in international law from NYU in 1974, has the scholarly-yet-stylish look of someone you might meet browsing off the Ring in one of Vienna’s art galleries or antiquariate. Spot him on the street in his overcoat and white scarf, and he is the picture of urbanity. It’s easy to imagine him descending the steps from the former Hapsburg capital’s renowned Oper into a snowy Viennese night. It’s a bit harder to imagine him hectoring and cajoling Iran’s theocrats into permitting more intrusive inspections of their facilities—or trying to fend off the demands of the United States and its European allies to escalate the matter by bringing their complaints to the United Nations Security Council. But that is precisely what has been occupying his time lately. And as he knows well, the stakes could hardly be higher: At issue is not only the question of war and peace between America and Iran but also the future of the global nuclear nonproliferation regime. Indeed, the viability of the current system of multilateral organizations that mediate among almost 200 nations and attend to the most challenging problems of the age hangs in the balance.

In early June, the ElBaradei view about how to deal with Iran received support from an unexpected quarter: the administration of President George W. Bush. In a rare reversal of a long-held policy, Bush okayed a new U.S.–European initiative that extended the promise to Iran of direct negotiations with the United States and a package of concessions if Tehran would cease its uranium-enrichment program, which Washington and some of its allies believe is aimed at giving Iran a nuclear weapon. (Until the spring of 2005, when it began to back a European effort, Washington had maintained that offering carrots of any kind would be a reward for bad behavior.) For ElBaradei, this turn of events came as welcome news and something of a vindication. “It is absolutely the right decision, and I’ve been saying that for more than two years,” he says. “The new initiative is quite good…. [It] has a lot of meat, which offers the option of normalizing with Europe and the U.S. and could have major implications for security in the Middle East. It is a few years overdue.”

In early June, the ElBaradei view about how to deal with Iran received support from an unexpected quarter: the administration of President George W. Bush. In a rare reversal of a long-held policy, Bush okayed a new U.S.–European initiative that extended the promise to Iran of direct negotiations with the United States and a package of concessions if Tehran would cease its uranium-enrichment program, which Washington and some of its allies believe is aimed at giving Iran a nuclear weapon. (Until the spring of 2005, when it began to back a European effort, Washington had maintained that offering carrots of any kind would be a reward for bad behavior.) For ElBaradei, this turn of events came as welcome news and something of a vindication. “It is absolutely the right decision, and I’ve been saying that for more than two years,” he says. “The new initiative is quite good…. [It] has a lot of meat, which offers the option of normalizing with Europe and the U.S. and could have major implications for security in the Middle East. It is a few years overdue.”

Even so, the success of the new proposal is far from guaranteed. In early July, Iran had declined to respond to the initiative, saying it would not have an answer until late August, angering the Western leaders who demanded action sooner. Many observers have taken such behavior as another indication that the Iranian government is determined to stall and postpone any talks until it has improved the enrichment process and even produced fissile material for weapons. After Tehran announced that there would be no quick reply forthcoming, Russia and China expressed their growing displeasure with Tehran’s foot-dragging by joining the U.S. and Europe in agreeing to seek a U.N. Security Council resolution ordering Iran to freeze some nuclear activities—or face sanctions. On July 31, against the backdrop of new hostilities between Hezbollah and Israel, the Security Council pushed again for some sign of cooperation, calling for Iran to cease its enrichment work by September. This elicited a defiant response from Tehran, which threatened to expand its nuclear program and perhaps cut off oil exports. ElBaradei’s belief in the necessity of diplomacy, though, is unshakeable. “There is no other way,” he argues. While ElBaradei understands that diplomacy can fail, he remains hopeful that the parties will negotiate, even if only because his experience on that score has been searing. “If I look at Iraq as an alternative, all I can say is we definitely should have a better system to settle our differences,” he observes. “If I read the figures that 120,000 civilians have died in the Iraq conflict, aside from the hundreds of thousands who died because of the ‘dumb sanctions’”—he shakes his head and concludes—“we clearly have a lot to learn about how to live in a so-called civilized society.”

The crisis ElBaradei is trying to manage has long been dreaded. In 1963, President John F. Kennedy warned that as many as 25 nations might acquire nuclear weapons by the 1970s. That nightmare scenario never materialized. In fact, for a time, the global nonproliferation effort could count more successes than failures. A passel of countries, including Argentina, Brazil, South Africa, Libya, South Korea and Taiwan, have pursued nuclear weapons programs and then thought better of it. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the nuclear-armed states that emerged from the wreckage—Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Belarus—agreed to turn over to Russia the weapons left in their territory. Beyond the countries whose possession of the bomb is recognized by international law in the form of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty of 1970 (NPT)—the United States, Russia (as the successor state to the Soviet Union), China, Britain and France—only India, Pakistan and Israel have developed nuclear weapons in the 40-plus years following Kennedy’s prophecy.

The crisis ElBaradei is trying to manage has long been dreaded. In 1963, President John F. Kennedy warned that as many as 25 nations might acquire nuclear weapons by the 1970s. That nightmare scenario never materialized. In fact, for a time, the global nonproliferation effort could count more successes than failures. A passel of countries, including Argentina, Brazil, South Africa, Libya, South Korea and Taiwan, have pursued nuclear weapons programs and then thought better of it. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the nuclear-armed states that emerged from the wreckage—Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Belarus—agreed to turn over to Russia the weapons left in their territory. Beyond the countries whose possession of the bomb is recognized by international law in the form of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty of 1970 (NPT)—the United States, Russia (as the successor state to the Soviet Union), China, Britain and France—only India, Pakistan and Israel have developed nuclear weapons in the 40-plus years following Kennedy’s prophecy.

In recent years, however, the successes have slowed to a trickle, and the danger of a cascade of nuclearizing countries appears more imminent than ever. The biggest gun of all pointed at the nonproliferation regime may well be Iran. For almost two decades, the Islamic Republic’s effort to develop nuclear energy has raised concerns in the West, where policymakers have long asked why a country afloat in oil needs to build reactors. The fears were confirmed when an Iranian dissident group announced in August 2002 that Iran was building two secret nuclear facilities, one for enriching uranium and another for making heavy water, which would be used for producing plutonium. An IAEA investigation confirmed that Iran had been conducting clandestine activities, and thereafter began several rounds of high-level diplomacy, led by Britain, France and Germany (the “EU-3”), while ElBaradei worked at the IAEA to persuade Iran to give up the program.

What has made the confrontation so vexing is the loophole at the heart of the existing nonproliferation language: Uranium enrichment is not illegal per se under the NPT. Signatories, such as Iran, are permitted to have, in technical parlance, the nuclear fuel cycle for the purpose of energy generation. The uranium used in reactors needs to be enriched until the level of the fissile isotope, U-235, is about 4 percent. The problem is that the same technology can be used to make weapons-grade (roughly 90 percent U-235) uranium.

As one Western diplomat who is involved in the politicking over Iran and, like most officials, will speak only on the condition of anonymity, explains, “What worries us is not diversion from a safeguarded plant but mastering the techniques at a safeguarded plant that leads to the creation of a clandestine plant.” Despite what the NPT says, as this diplomat puts it, “Good sense and legal obligation are in conflict.”

What ultimately makes the issue so freighted is the widely held belief that Iran represents a tipping point. North Korea’s acquisition of a nuclear capability set off loud alarms beginning in the 1990s, but the consequences of its breakthrough were seen as limited compared with what might happen if Iran builds a nuclear arsenal. The reason is that North Korea is seen as a deadend regime with few ambitions beyond its own survival.

Iranian acquisition of nuclear weapons, on the other hand, would send shock waves through one of the world’s most economically vital and politically volatile regions. Imagine the Balkans around 1914, the global powder keg—only now the gunpowder has been replaced by highly enriched uranium and plutonium—and you have an idea of one potential outcome of the Iran crisis. Imagine another American military intervention in the Persian Gulf on the heels of the debacle in Iraq (even though most strategists speak of a sustained air campaign and not the commitment of ground forces) with the attendant upheaval in the area and throughout the Muslim world, and you have another. Mohamed ElBaradei has plenty to worry about.

Professor Thomas Franck, front row, fourth from the left, in 1972, with international fellows including Mohamed Elbaradei, in the far right corner, and Antoine van Dongen, front row, second from the left.

With so much riding on his work, it’s remarkable how little attention ElBaradei has received. Scan Nexis and you will find no full-scale profiles of him in English—indeed, there are few that are more in-depth than the short one on the IAEA Web site. But then he is somewhat unusual as a public figure. Animated and voluble in conversation, but averse to the spotlight, ElBaradei is a man who would prefer to be at home in the evenings plowing through piles of work in the company of his wife, Aida—who must have been Vienna’s most elegant kindergarten teacher until her recent retirement—instead of taking part in the never-ending roundelay of Viennese diplomatic receptions. His aides seem used to defending him against the charge that he is aloof. “People sometimes think he’s arrogant,” says Tariq Rauf, a senior IAEA adviser and member of the ElBaradei kitchen cabinet, “but it’s more that he’s shy. He’s actually a very warm person.”

He is a genuinely devoted family man—a fact universally cited by critics and friends alike—who delights in spending time with his daughter, Laila, who is a lawyer in London, and his son, Mostafa, who works in that same city as a production engineer at CNN. Although ElBaradei travels relentlessly, he sees the two of them frequently, and they are always in touch. “We speak almost every day or every other day,” Laila says. “He’s learned how to text message, and he sends me great one-liners. He has a great sense of humor and I’ve always been sorry he didn’t have a job where he could use his sense of humor.” Through one crisis after another, family has been ElBaradei’s refuge. Laila recounts, “No matter how busy my dad is, he always finds time for the boring minutiae in my life. I’m getting married in September and he’s interested in what color the flowers should be and whether we should have a band or a D.J.”

The absence of press coverage may also have something to do with the instinctive belief by many in the media that an international civil servant untainted by scandal who is devoting his efforts to nuclear disarmament must be a saint of sorts. The suspicion, therefore, as George Orwell wrote about Mahatma Gandhi, is that ElBaradei would evoke “aesthetic distaste” in person. But ElBaradei is not a saint. He is a likable, worldly man who is anything but austere.

Mohamed ElBaradei was born on June 17, 1942, in Cairo—a dangerous time and place. Although Egypt was nominally independent, it still was dominated by Britain and, at that moment, Nazi troops under General Erwin Rommel were menacing from the west. The First Battle of El Alamein occurred just a few weeks after ElBaradei’s birth, halting the German advance into Egypt outside of Alexandria. He came of age in the era of Gamal Abdel Nasser, the Egyptian leader who cut the cord with Britain—a charismatic champion of anticolonialism, Pan-Arabism and the rights of the developing world.

ElBaradei comes from a family dominated by lawyers. Among the most distinguished were his maternal grandfather, Ali Haider Hegazi, who sat on Egypt’s Supreme Court, and his father, Mostafa ElBaradei, who rose to become president of the Egyptian Bar Association. ElBaradei enjoyed a youth of privilege in the clubs of Cairo and vacation homes of Alexandria, where the wealthiest Cairenes had their retreats. Yet even his father ran afoul of Nasser in 1961 by calling for democracy and a free press. The elder ElBaradei was harassed for his opinions, though he was later rehabilitated and recognized as a major figure of his era.

ElBaradei graduated from the University of Cairo in 1962 with a degree in law and joined the Egyptian foreign service, for which he was posted to the U.N. mission in New York. There he took advantage of a part-time master’s program that the NYU School of Law offered and studied under Professor Thomas Franck, now the Murry and Ida Becker Professor of Law Emeritus. Eventually, during the early 1970s, he took leave from his job to work for his J.S.D. in international law.

Franck, who is still close to his former student, remembers him as being “very much as he is today…cautious, levelheaded, sound, consciously unexciting—above all, sensible, moderate.” Anti-Zionism, of course, was a core tenet of Nasserism, and while ElBaradei was in New York, Egypt and Israel fought two wars. Still, the young Egyptian wasn’t a prisoner either to national sentiment or to his profession as an Arab diplomat. As Franck recalls, “His view was not your basic view of Israel. He pretty well knew the fact that Israel existed and that was not going to change. He was for finding some modus vivendi. He was always far more than an Egyptian studying in the United States, and he never presented the case like an Egyptian official.” A fellow student from ElBaradei’s early days in New York and now a lifelong friend, Antoine van Dongen (M.C.J. ’71, LL.M. ’72) recalls that the future IAEA director general “could be totally frolicky and asinine, as we all could be, and then be totally serious in debate and hold his own in conversation.” Van Dongen, who is the Netherlands’ ambassador to Sweden, also saw a trait in ElBaradei that has become a hallmark of his career: “If he thought he was right, then he really thought he was right.”

If ElBaradei’s temperament was already formed by the time he reached New York City, he still had a powerful desire to broaden his horizons. The 15 years he spent (with some interruptions) in the city were what he calls “really the formative years.” He bought a subscription to the opera, taught himself about modern art—for which he retains a

passion—and became a diehard fan of both the Yankees and the Knicks. Just the thought of that period puts a charge in his voice. “I still vividly remember watching at the dorm when the Knicks won the 1973 world championship…Earl the Pearl [Monroe], [Walt] Frazier and Dave DeBusschere!” he exclaims before a tone of wistful exasperation creeps in, one known to Knicks fans everywhere who have been waiting for a repeat of that miracle. “And I have been following them from abroad for the last 33 years.”

Longtime friends and close aides testify to the deep imprint that New York made. His speechwriter, an American, Laban Coblentz, observes that to this day ElBaradei “peppers his speech with Americanisms like ‘step up to the plate’ and ‘full-court press.’” New York did more than give ElBaradei a new set of interests, though. “This was the time of the counterculture,” he recalls, “and the Village was really the hub of everything that was happening.” Although cosmopolitan by Egyptian standards, ElBaradei was confronted with a variety that was overwhelming and exhilarating. “New York,” he says he came to recognize, “is this microcosm of the world; it is the melting pot of every nationality of every race. You realize that we are one human family. I came to realize that living in New York.”

After he finished his doctorate, ElBaradei was posted by the Egyptian foreign service to its mission in Geneva, where he continued to work on the multilateral issues handled by the various U.N. agencies there. From 1974 to 1978, he served as a special assistant to Egyptian Foreign Minister Ismail Fahmy and subsequently worked with Boutros Boutros-Ghali, who later became U.N. secretary-general. In 1980, the connection ElBaradei had forged with NYU and, in particular, with Thomas Franck proved fortuitous for the rising diplomat. The U.N. asked Franck to lead its Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR), an agency that, despite its name, undertook internal audits and evaluations of U.N. programs. Franck made a condition of his hiring that he be able to bring along ElBaradei, and with that the Egyptian returned to New York and joined the international civil service. During this period, between 1981 and 1987, he was also an adjunct professor at the NYU School of Law. He eventually came to the attention of Hans Blix, then the new director general of the IAEA, who hired ElBaradei to open the Vienna-based organization’s office in New York in 1984. At the IAEA, he flourished, moving to headquarters as chief of the legal division in 1987. He later became head of external relations—essentially the agency’s foreign minister—responsible for overseeing contact with the 100 or so member nations.

ElBaradei’s ascent to the top job at the IAEA provides one of the more comic episodes in the often-delicate apportionment of desirable spots in the international civil service, though none of the missteps was his. In the mid-1990s, it became clear that Blix, a legendary leader of the IAEA, would step down after the completion of his fourth term, and, unusually, no country stepped forward with a strong nominee.

Washington’s ambassador to the IAEA at that time was John Ritch, a highly regarded envoy who decided that it was unwise to leave the succession to chance. As he recalls the story, Ritch, now director general of the World Nuclear Association, which promotes the peaceful use of nuclear energy, felt at the time that the opening at the top provided an opportunity to put a capable man in the job and send a valuable message of goodwill to the developing world. The IAEA had been run by Swedes for 36 of its 40 years (the first director, who served a single term, was former U.S. Congressman Sterling Cole). Ritch, who was a friend of ElBaradei’s, recalls, “Mohamed combined affability, experience and a Western orientation with a high sensensitivity to the developing world’s perspective.” He was, in Ritch’s view, the complete package because, he says, “there is always a chasm between developing countries and developed countries, with the former putting a lot more emphasis on receiving assistance and the latter wanting to focus on nonproliferation issues. ElBaradei, with his nonproliferation credentials and Western perspective, seemed a good person to bridge the gap.”

At this point, behind-the-scenes diplomacy turned into a high-level game of telephone. Word reached Cairo that an Egyptian could become director general, and President Hosni Mubarak decided to nominate a personal favorite of his, Mohamed Shaker, who would later serve as Egyptian ambassador to the U.K.

Shaker, however, was viewed as exactly the kind of person the U.S. did not want—a contentious proponent of Third World causes who, it was felt, would not provide the necessary leadership. In Washington, he became known as the “other Mohamed,” and a delicate dance ensued to persuade Cairo that an Egyptian could indeed become the IAEA’s director general, just not the one the Egyptian president wanted. The board of the IAEA held an informal vote, Shaker was turned down and ElBaradei was elected. “Nonetheless, handing this job to an Egyptian was a big step. Had Mohamed not been in Vienna, had he not had the support of the American ambassador and a totally Western persona, he never would have been considered,” says Ritch. For all that made him appealing to the U.S., however, ElBaradei has been nobody’s puppet, and his independence has at times made him the target of sharp American criticism.

The role of the organization ElBaradei inherited has shifted considerably during its existence. The IAEA grew out of the Atoms for Peace initiative that President Dwight D. Eisenhower unveiled at the U.N. in 1953. The core idea was that the power of the atom offered fabulous promise in terms of cheap energy, and the U.S. and others who had the technology would share it with those who wanted it, provided they forswore the development of atomic weapons. The IAEA, which was born four years later, was envisioned as the agency that would regulate this bargain.

As time went on, however, the agency’s role as middleman in the transfer of peaceful nuclear technology did not develop as quickly as its role as global nuclear cop, which was enshrined in the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. The treaty provided that the IAEA could inspect a signatory’s nuclear facilities, but only those the signatory declared, leaving open the possibility of clandestine facilities. The inadequacy of that arrangement became clear after the 1991 Gulf War, when it was revealed that Saddam Hussein’s nuclear program had been alarmingly close to giving him the bomb he coveted.

In the years since, the IAEA has added an “additional protocol” to its earlier safeguards agreements that gives the organization’s inspectors enhanced access to nuclear facilities. Thus far, 107 countries have signed the protocol, but only 74 have ratified it. (In late 2005, after the IAEA rebuked Iran for not cooperating sufficiently with inspections, Tehran announced that it would no longer act as if bound by the protocol, which it had signed but not ratified.) Efforts to strengthen the nonproliferation regime also failed at the latest five-year review conference of the NPT, which was held in New York in May 2005.

If events have conspired to make the nonproliferation regime look more like a leaky and possibly sinking ship, ElBaradei, like his predecessor Blix, has done an exceptional job of keeping the pumps operating and the vessel afloat. Part of his success has been the result of his passionate belief in multilateral institutions and their ability to deliver fairness in international politics. He explains, “The whole concept of multilateral institutions is that you sit together and cut a deal that is fair and equitable to everybody…. You never get your way 100 percent and I don’t think in any area now any one country can get 100 percent…. One-hundred-percent security for one country is 100 percent insecurity for another, so you just can’t have it.” In this regard, ElBaradei is a descendant of the dedicated international civil servants who worked in the heroic age of the U.N., such as Ralph Bunche and the director general’s own hero, Dag Hammarskjöld. One American who has long had dealings with ElBaradei sums it up by saying, “He sees himself more as a representative of the nonproliferation regime and international diplomacy.”

Passion and high-mindedness, of course, are only part of the equation. Another key has been maintaining the agency’s reputation. According to David Waller, deputy director of the IAEA, who is the highest-ranking American at the agency and was put forward for his position by President George H.W. Bush after serving in the Reagan administration, ElBaradei “believes credibility is the lifeblood of this organization, and when we lose that, we’re finished.”

He has preserved that credibility in several ways. The first is by running an organization whose ethical standards have never been challenged. While the rest of the U.N. system has weathered a series of debilitating crises, including the corruption of the Oil-for-Food program in Iraq, the IAEA has been scandal-free and is regarded as the

jewel in the crown of the network of international organizations. Another is by upholding the original vision at the heart of the NPT. That is, he has continued to call for those NPT signatories that have nuclear weapons to adhere to the treaty’s “bargain,” which requires them to reduce their arsenals and pursue the abolition of nuclear weapons, and in return, states that do not possess the weapons already, don’t develop them.

Although the political elites of the nuclear powers have long rolled their collective eyes at this quid pro quo, ElBaradei has never tired of invoking it and prodding the countries that pay much of his agency’s budget—and provide it with a large amount of the intelligence that is essential to its work—to do their bit. At times he has voiced this in an acid tone, likening the nuclear weapons states to those who “continue to dangle a cigarette from their mouth and tell everybody else not to smoke.” In particular, recent moves in the United States to develop a new generation of nuclear warheads have elicited his outrage. “How can the U.S., on the one hand, say every country should give up their nuclear weapons and on the other develop these bunker-buster mininukes?” he asks.

Finally, ElBaradei has maintained the standing of the IAEA by refusing to bend before the powerful—or to shy away from telling them unwelcome truths, as he did during the run-up to the Iraq war. This characteristic of the IAEA director general only became visible midway through his tenure, after the Bush administration began. So far as the Clinton administration was concerned, dealings with ElBaradei were smooth, according to Gary Samore, who served as senior director for nonproliferation on the National Security Council. One continuing concern was Iraq’s nuclearweapons program, which the IAEA inspectors believed had been fully dismantled before they were thrown out of the country in 1998. “We were pretty confident that Iraq’s nuclear program had been accounted for,” Samore explains. “The only issue was the IAEA wanting to declare that the file was closed, and they wanted to shift to longterm monitoring. We didn’t want them to do that because it would add to pressure to lift sanctions.” With inspectors unable to regain entry into Iraq, the issue of keeping the “nuclear file” open was not a very contentious one.

Given his history as an American favorite, what came later in ElBaradei’s dealings with the remaining superpower was surprising and bitter. The turning point came after the attacks of September 11 and the Bush administration’s decision to end the regime of Saddam Hussein. As he sought to build public support in 2002–03 for an invasion, President George W. Bush told the nation about aluminum tubes that Hussein was procuring for use in the centrifuges used for enriching uranium and about Baghdad’s effort to buy uranium in Niger. Vice President Dick Cheney declared his “absolute certainty” that Saddam was reconstituting his nuclear program and working to build a bomb.

An ambassador, the 17th-century English diplomat Henry Wotton famously declared, is an honest man sent abroad to lie for the good of his country. The task of a senior international civil servant is worse: He or she must tell the truth to powerful leaders for the good of an anonymous international community, and in doing so, persuade them to reconsider their actions without so angering them that they turn vengeful. After the tense diplomacy of late 2002, Hussein allowed teams of U.N. and IAEA inspectors to return to Iraq to search for signs of chemical, biological and nuclear weapons. As everyone remembers, the inspectors found nothing to change the IAEA’s conclusion that Iraq had no nuclear-weapons program. On March 7, 2003, ElBaradei reported in sober terms to the U.N. Security Council that on the basis of inspections at 141 suspected sites, there was “no evidence or plausible indication of the revival of a nuclear-weapon program in Iraq.” In addition, IAEA researchers argued—as many within the U.S. intelligence community did secretly as well—that the aluminum tubes were for conventional battlefield rocket production. IAEA personnel also established that the documents that purported to show that Iraq was seeking to buy uranium in Niger were forgeries.

None of this endeared Mohamed ElBaradei to the Bush team. Secretary of State Colin Powell, who had staked his reputation a month earlier on charges of Iraqi subterfuge, responded to the director general’s remarks by saying, “I also listened to Dr. ElBaradei’s report with great interest. As we all know, in 1991 the International Atomic Energy Agency was just days away from determining that Iraq did not have a nuclear program. We soon found out otherwise.”

The remark was true but not exactly on point, since pre–Gulf War inspections were performed the traditional way—under Iraqi rules. Because of the U.N. resolution under which the 2003 inspections were conducted, inspectors had universal access and Iraqi compliance was required to fulfill the terms set by the Security Council. Nonetheless, Cheney announced on television that the IAEA had “consistently underestimated or missed what it was Saddam Hussein was doing,” though he adduced no proof for his point, adding, “I don’t have any reason to believe they’re any more valid this time than they’ve been in the past.” As one IAEA insider recalls, ElBaradei, going every bit of the way to persuade the decision-makers in Washington to rethink matters, met in 2003 with Bush, Cheney and Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld. This individual describes that meeting as an empty ritual. “You could tell that they were wondering why they were wasting their time with him,” he says. ElBaradei later termed the outbreak of war in Iraq on March 20, 2003, “the saddest day of my life.”

What is striking about ElBaradei’s performance during this episode is the extraordinary composure he showed throughout. It was the ultimate nightmare scenario for the leader of an international agency: to be pitted against his main funder, the most powerful country on the planet and the one whose support is most vital to his group’s work. Although people around him confess those were dark days, “during the period of pressure, he never wavered, just did his business,” says one diplomat who watched him closely. T.P. Sreenivasan, then India’s ambassador to the IAEA and Austria, said that ElBaradei fully recognized what he was up against. “He was agonizing over it, because he didn’t want a war,” says Sreenivasan. “He didn’t want to provoke the Americans, but at the same time he was very precise and very clear.”

As with many individuals with powerful convictions, it is not easy to say where they draw their strength. “What makes him tick?” repeats his son, Mostafa, in response to a question. “It’s almost as much a mystery to me…. A lot of it comes from his father and his upbringing. My grandfather was a very moral man. From what I’ve been told, speaking out in the time of oppression in Egypt for democracy and freedom, I expect some of [my father’s] strength comes from that and from our family. He has his set of beliefs and his value system, and he is not swayed either way.” ElBaradei’s old friend Antoine van Dongen agrees: “He has an inner strength that he hardly needs to flaunt because people know it is there.” ElBaradei himself feels that the ordeal emboldened him. He says, “If you are a sole individual, and you’re up against the sole superpower, and you can come out on the winning side…it gave me a lot of credibility afterward. I was one of the few—and I don’t like to say it—who got it right on Iraq. It shows that you really have to stick to the facts.”

That extra toughness was valuable, too, because being right about Iraq was not the solution to ElBaradei’s problems with the Bush administration. With ElBaradei’s second term coming to an end in early 2005, U.S. officials began seeking a way to prevent him from winning a third. John R. Bolton, the hard-charging conservative who served as Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security and was later given a recess appointment as U.S. ambassador to the U.N., made denying ElBaradei a third term a personal mission. According to Lawrence Wilkerson, who served as chief of staff to Secretary of State Colin Powell, Bolton was “going out of his way to bad-mouth him, to make sure that everybody knew that the maximum power of the United States would be brought to bear against them if he were brought back in.”

Since the campaign to remove ElBaradei was conducted behind the curtains of diplomacy, it is not clear how much the effort was motivated by anger at the role he had played in the run-up to the Iraq war and how much by the belief that he was “soft on Iran,” as one U.S. official put it. The attempt has also been widely depicted as a solo one, but diplomats from other Western countries concede that there was broader interest in finding a new leader for the agency—and some believe a coalition might have been assembled to block ElBaradei’s reelection. According to one non-American Western diplomat who declined to be identified, there have been fairly widespread qualms about ElBaradei’s leadership: “Our frustrations with him have centered on the fact that he has never had much sympathy for halting work on enrichment and reprocessing in Iran, despite all the information the inspectors have brought to light.”

It was, nonetheless, the U.S. treatment of ElBaradei that filled the headlines. According to press reports, IAEA officials complained of a cut in the flow of intelligence from the U.S., which is essential for the IAEA’s work. In December 2004, the Washington Post reported that U.S. intelligence agents had been tapping ElBaradei’s calls, possibly in the hope of finding indications that he was trying to help Iran avoid a confrontation over its nuclear program. The leak about the surveillance may well have come from one of any number of career U.S. government officials who were appalled that the U.S. would seek to oust ElBaradei.

Whether the eavesdropping produced anything useful or not, once the story became public, the coalition-building collapsed. For a time, Powell claimed that Washington was motivated by its belief in the “Geneva Rule,” a general agreement by major donors to international organizations that two terms for leaders of those institutions was enough. But even Powell admitted that the rule was not uniformly observed; in fact, at the IAEA Hans Blix served four terms, and his predecessor, Sigvard Eklund, served five.

So the argument made no headway, nor did the U.S. effort to persuade a leading Australian diplomat to take the job, or to find a suitable South Korean or Brazilian. (Questions have been raised about both countries’ intentions regarding their nuclear programs, making their candidates untenable.) No other country ever publicly owned up to sharing America’s concerns, and ElBaradei was reelected to his third term in June 2005. Fortified by his vindication on the issue of Iraq’s nuclear efforts, the director general was unfazed. “I was in a win-win situation,” he says. “If I get reelected, that is an affirmation of the international community. And if not, I will have the silent majority of the world understanding that this was the result of a conflict with a superpower…and I would be going out a hero in the eyes of the people.” As his son, Mostafa, puts it, in the last few years, Mohamed ElBaradei “has had crises on his hands, but he has grown more confident as he has gone along.”

Professional survival is one thing; global acclaim is another. The latter came ElBaradei’s way four months after his reelection, when he was sitting at home one morning watching CNN with his wife and heard his name pronounced by someone speaking Norwegian. (The shock was so great, says Aida ElBaradei, “I can understand that people can have heart attacks from joy.”) The chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, Ole Danbolt Mjøs, had tried to call ElBaradei at his office but to no avail, so the announcement was made without informing the winner. There had been plenty of buzz about ElBaradei and the IAEA being in contention again for the prize (they had reportedly come close the year before). But not having heard anything, he had assumed it had gone to someone else.

ElBaradei may have been shocked, but the Nobel Committee’s decision to give the prize jointly to the IAEA and its leader was not exactly surprising. It has been awarded eight times to officials of agencies within the U.N. system and at least half a dozen times to proponents of nuclear disarmament. As individuals and institutions, these two groups have been particularly attractive to a committee charged with carrying out the wishes of Alfred Nobel, the 19th-century inventor of dynamite, who said he wanted his legacy awarded to those who had achieved great strides toward the “abolition or reduction of standing armies.”

What seems to have particularly attracted the Norwegians was how honoring the IAEA and its leader would lend support to the international system, and in their announcement they said explicitly that at a time of a growing nuclear threat, the “Nobel Committee wishes to underline that this threat must be met through the broadest possible international cooperation. This principle finds its clearest expression today in the work of the IAEA and its director general.” ElBaradei was singled out as “an unafraid advocate” of the nonproliferation regime.

Though Mjøs denied that the award was “a kick in the shin of any nation, any leader,” the language suggested that ElBaradei’s recent run-ins with the U.S. government were very much on the minds of the committee members. The award followed the 2002 prize to former President Jimmy Carter, who had been outspoken in his opposition to the war in Iraq, and the 2005 prize in literature to British playwright Harold Pinter, a vitriolic critic of American foreign policy.

Ever the diplomat, ElBaradei insisted that the world’s preeminent award not be seen as a reproach. “I don’t see it as a critique of the U.S.,” he said at the time. “We had disagreement before the Iraq war, honest disagreement. We could have been wrong, they could have been right.” Instead, he said, the prize should be seen as “a message: Hey, guys, you need to get your act together, you need to work together in multinational institutions.” In the time between the campaign to unseat ElBaradei and the announcement of the Nobel, the dramatis personae had changed in Washington. From the State Department, both Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and Under Secretary for Political Affairs R. Nicholas Burns congratulated the director general.

Not everyone was so laudatory, however, and the reactions to the prize say something about the impossibility of satisfying everyone while running an agency that deals with things nuclear. Mike Townsley, a spokesman for the environmentalist group Greenpeace International, which strongly opposes nuclear power, commented that ElBaradei was trapped by the agency’s “contradictory role, as nuclear policeman and nuclear salesman.”

John Ritch disagrees. “The IAEA will always be subject to ideological criticism for even existing. But it could hardly be more unlike a salesman. Indeed, a valid criticism would be that the agency has not fully embraced the urgent necessity of promoting the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. The IAEA should be leading the way.”

During the Nobel festivities in Oslo, ElBaradei enjoyed his share of adulation. “Endured” might be a better way to put it, though, as he was thrust into a spotlight that all but overwhelmed him. One of the events involved a concert in his honor, and he came onstage to deliver a short off-the-cuff speech. The audience gave him a prolonged round of applause before he started, and when ElBaradei finished speaking, he received another resounding ovation from the 4,000-member audience. After a few seconds of clapping, he turned to walk off—only to be pulled back on stage by actresses Julianne Moore and Salma Hayek.

The prize ceremony also afforded the winner the platform of a lifetime, and for that ElBaradei overcame his shyness. Although even close friends consider him an uneven speaker, he delivered a remarkable piece of oratory, spelling out his understanding of the myriad interconnections among some of the ills that plague the world, from ground-level poverty to weapons of mass destruction. The connections, he continued, can easily be traced to the most fundamental inequities: “In the real world, this imbalance in living conditions inevitably leads to inequality of opportunity and, in many cases, loss of hope. And what is worse, all too often the plight of the poor is compounded by and results in human-rights abuses, a lack of good governance and a deep sense of injustice. This combination naturally creates a most fertile breeding ground for civil wars, organized crime and extremism in its different forms.”

“It’s not just poverty per se, it’s the sense of humiliation and injustice. When somebody feels humiliated, they just go bananas, and that is what happens,” ElBaradei observes while talking about the sociology ofconflict in his Vienna office. Like many analysts of radical Islamist violence, ElBaradei believes that the rise of the new terrorism—and September 11 itself—has roots in a sense of civilizational humiliation. The commitment to alleviate suffering is one that he takes personally, too. The $1.3 million in Nobel prize money was divided equally between the IAEA and its director general. The agency donated its share of the award to a new fund for cancer treatment and childhood nutrition. ElBaradei gave his half of the prize to a group of Cairo orphanages with which his sister-in-law works.

The notion that we have our most fundamental priorities all wrong falls into the category of all-but-universally-accepted and is therefore something that few grown-ups, especially those in places of international responsibility, would think of advocating seriously. But ElBaradei has made it to the pinnacle of international service and does not tire of making that point—to the irritation of officials who believe that the interconnectedness of all things and the failures of the world order are not the IAEA director general’s business. “In the Nobel speech, he went well beyond his mandate,” grouses one senior American official. In the view of this diplomat—and more than a few others—ElBaradei’s job is to run an international organization with a technical mandate, one that requires that he present factual accounts of what different countries are doing with their nuclear facilities. Taking on the structure of global politics is something for national leaders and the secretary- general of the U.N.

The critics may have a point, but, Nobel in hand, ElBaradei is not shying away from the issue. The international community’s misallocation of resources between the tools of conflict resolution and those of war is a subject that he turns to in conversation repeatedly and in a tone that suggests he has neither illusions about the likelihood of broad change nor regret for voicing his dismay. “I think the whole budget of the entire U.N. system plus the other [multilateral] organizations is not more than, like, $5 billion. And against that you are talking $1 trillion on armaments…. When you look at the figures, it just shocks you,” he observes. Turning to another side of the equation, he says, “We also pay less than 10 percent of what we spend on armaments on development. Well, that comes back to haunt us in the form of extremist groups, in the form of disaffected people…. We look at the symptoms; we do not look at the big picture.”

The IAEA’s annual budget is $347 million (€273 million), and most of that goes to the agency’s inspections work. But to the extent he has been able, ElBaradei has pushed projects that address concerns at what might be called the bottom end of his great chain of human unhappiness. Using a variety of nuclear-related technologies, IAEA scientists are working on improving agricultural yields in developing nations, allowing for more efficient water use and working to bring advanced cancer therapy to nations that have little or none available.

A profound desire to avoid military conflict and a high-wire talent for redefining the boundaries of his job have been the hallmarks of ElBaradei’s tenure at the IAEA. Both of these qualities have been severely taxed by the continuing tensions over Iran, and how that plays out will likely provide the final verdict on his time in office. For a while, it looked as though there was reason for optimism that a full-blown crisis would be escaped. In October 2003 Iran forged an agreement to suspend its enrichment activities while negotiations were underway with the EU-3. But in August 2005, the country reneged and resumed efforts at a facility in Isfahan. Positions hardened after the election of extremist Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who declared Iran’s absolute determination to continue doing what it was doing.

The failure of the negotiations soon put ElBaradei and the U.S. at loggerheads again. Under the IAEA charter, if the director general reports to his board of governors that a signatory is not living up to its treaty agreements and is found in violation by the IAEA board, that country is to be reported to the U.N. Security Council for further action. But in the eyes of the U.S. and its allies, ElBaradei was ducking his responsibility and working beyond his portfolio to keep the problem at the IAEA and prevent an escalation of tensions. As one Western diplomat, who acknowledges that he finds ElBaradei both an admirable and infuriating figure, puts it, “Once the suspension was no longer honored by Iran, we had another problem with him. He was trying to influence members not to take a direction that was provided for by IAEA statutes.”

ElBaradei did so, critics contend, by avoiding inevitable conclusions in his reports and through behind-the-scenes entreaties to officials from the various countries on the board to go slow on Iran. Repeatedly, the reports have documented an array of failures by Iran to comply with its treaty obligations, but ElBaradei has avoided declaring that Iran has a nuclear-weapons program, angering Washington and other Western capitals. “Some day, we’ll see the ‘director’s cuts’ of the reports,” says one American diplomat, whose opinion is shared by many, including some who are ardent critics of the Bush administration. “There is no question that they go through an editing process…. He’s not prepared to confront the Iranians as strongly as we are.”

It is the responsibility of the IAEA director general to oversee the production of reports for the organization’s board and the U.N., but in this case, his critics say, ElBaradei has used his stature to steer the process away from a confrontation with Iran—and that this is another instance of his mixing in the politics of the issue rather than confining himself to the technical issues with whose adjudication he is charged. Even ElBaradei’s former deputy, Pierre Goldschmidt, who oversaw many of the inspections, took a notably tougher stance after his 2005 retirement and urged the Security Council to get involved. “ElBaradei says that any judgment about Iran should be made on their intentions,” he told the Sunday Telegraph. “My view is that we should look at the indications, not the intentions, and then decide…. As things stand, we cannot prove that Iran has a military nuclear programme. But do you have indications that this is the case? This is the question I think everyone should now be asking.”

The same diplomat who criticized ElBaradei for seeking to persuade board members not to refer the issue of Iran to the U.N. believes that the director general is “a political animal and a diplomat, and he knows diplomacy is more fun than managing a large institution.” A further part of this critique is that ElBaradei has prevented the U.S. and its allies from putting all the necessary pressure to bear on Iran, and that his desire to prevent armed conflict is at odds with his technical duties. But ElBaradei rejects the contention that he is out of line. “I’ve heard that a lot in the past. I don’t hear it as much now. People said I was talking outside of the box and this is a technical organization. I think that is a fallacy,” he says. “Yes, this is a technical organization, but we work in a very politically charged environment, and you cannot separate the politics from the technical work we do.” Much of his job, he says, is to identify the various options available to the parties: “I don’t meddle in the politics, but I have to be aware of the political implications of what we do. And I feel I owe it to the member states to tell them how I see things from where I sit.” He adds, “I look at the big picture. I have to do verification, but I also have to see how the international community can use this for a peaceful resolution.”

Underlying his actions, his aides say, is a sense that moving the issue to the Security Council would be a fateful mistake that could lead ultimately to military action. Throughout the latest crisis, the U.S. has made clear that its objective is to obtain a resolution under Chapter VII of the U.N. Charter, which would make the issue one of a threat to peace. In principle, that could open the door for the U.S. and others taking it upon themselves to enforce the resolution in Iran militarily, as Washington argued it did in invading Iraq. The White House continues to call for a diplomatic solution, and no one close to the issue believes that military action would occur before a sustained effort to isolate and penalize Iran economically through sanctions. Ultimately, ElBaradei would lose the fight against referring Iran to the Security Council, but Russia and China have been reluctant to authorize sanctions, thus postponing a possible conflict. Still, those close to ElBaradei argue that he does not want to go that route, at least as long as IAEA inspectors can work in Iran. As his speechwriter, Coblentz, explains, ElBaradei “believes that confrontation is so counterproductive and that it will take so long to pick up the pieces that…diplomacy has to be the answer.”

For ElBaradei, it comes down to a matter of moral responsibility: “You can act as a bureaucrat in the negative sense and do your job and go home. Or you can realize that there is something you can do to make people safer and better off. And you do what you have to do.”

—Daniel Benjamin, coauthor of The Next Attack: The Failure of the War on Terror and a Strategy for Getting it Right, is a senior fellow in the International Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. He served on the National Security Council during the Clinton administration.

—