In One Short Year, Remembering a Life

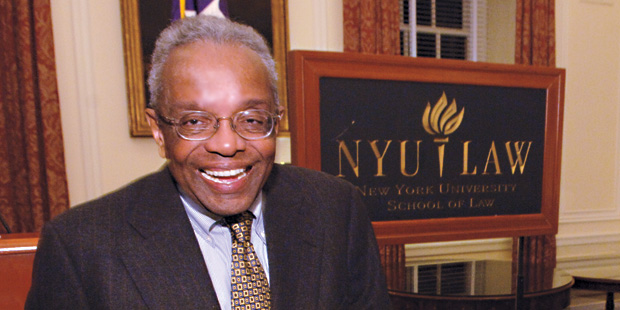

Printer Friendly VersionWhen constitutional law scholar and critical race theory pioneer Derrick Bell passed away last October at age 80, NYU School of Law, which welcomed him as a visiting professor more than 20 years ago, seemed not quite ready to let him go. At the family’s beautiful memorial service at the Riverside Church, NYU President John Sexton, Ms. founder Gloria Steinem, and Harvard Professor Charles Ogletree Jr. spoke, and Jessye Norman sang a tearful and moving rendition of “Amazing Grace.” But the Law School continued a conversation for several months, invoking his memory at many events including the annual Derrick Bell Lecture on Race in American Society in November; the Bell Annual Gospel Choir Concert, performed with even more tears than usual; and the Black, Latino, Asian Pacific American alumni organization Spring Dinner, where he was celebrated alongside other leaders of the civil rights movement. But the galvanizing event was the posthumous dedication to him of the 69th volume of the NYU Annual Survey of American Law, when Bell was remembered as a compassionate teacher and scholar by his former students, colleagues, and deans.

Bell famously came to NYU in 1991 after leaving Harvard Law School to protest the utter lack of tenured black women on the faculty. It was not his first such act. In 1985 he resigned as dean of the University of Oregon Law School when the faculty failed to give a tenured job offer to an Asian American female candidate he recommended. Earlier, in the 1960s, he left his first post– law school job in the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice, where he was the only African American lawyer, when he was asked to give up his NAACP membership. He then became the first assistant counsel at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, working for Thurgood Marshall and supervising more than 300 school desegregation cases in Mississippi. Dean Richard Revesz told the assembled guests, “The two qualities that I think best exemplify Derrick’s life and that weave in and out of everything he did professionally are courage and integrity.”

The students and colleagues who spoke at the dedication ceremony spanned Bell’s career, from his years at the NAACP through NYU. Norman Dorsen, Frederick I. and Grace A. Stokes Professor of Law, who first met Bell in the 1960s, remembered him as a dedicated mentor: “He felt a special urgency about monitoring African Americans and other students who were making their way through the maze of legal education. These students often came from families that had not previously had a member who attended college. He considered his relations with students to be a deeply important responsibility and opportunity.”

Sexton, who was dean of the Law School in 1991 and invited Bell to NYU after the Harvard imbroglio, recounted how he told Bell that he could be the “Walter Alston of legal education” by signing only one-year visiting professor contracts but staying at his job for decades. Sexton first met Bell in 1976, when Bell taught him at Harvard Law. “He had the capacity that the really great teachers have,” said Sexton, “to make you think about something completely differently from the way you thought about it before you began to work with him…. I’m not sure I’d be here today if it hadn’t been for his pushing me as a scholar.”

That notion that Bell inspired students to devote their careers to the law was echoed by other speakers. Gabrielle Prisco ’03, director of the Correctional Association of New York’s Juvenile Justice Project, first met Bell in the fall of her 1L year after she told Sexton that she felt out of place. He introduced her to Bell, who invited her to sit in on his Constitutional Law class and to join his students and him afterward for their regular dinners. After graduating, Prisco returned to NYU Law as a Derrick Bell Fellow, teaching with Bell and engaging in scholarship on race and racism in American law. “I learned how to ground my thoughts on justice and on fairness in the framework of the Constitution and in legal thinking,” she said. “Derrick reminds us that the work we do in the world matters, that we are the problem-solvers of this time and place, and that much rests in our hands and in what we do with that.”

Patricia Williams, James L. Dohr Professor of Law at Columbia Law School, was another of Bell’s students at Harvard Law and, she says, became a critical race theory scholar and professor because of him: “He made ideas come alive, he made the dry pages of treatises vivid. He never let us forget the human stories behind every tract, every suit, every appeal. He imbued legal education with a sense of purpose and responsibility, and we weren’t there for ourselves alone, but to live up to a calling and to be of service.” More personally, she said, “He helped me reframe the sense of isolation and intimidation I felt as causes, and as precisely the reasons there was an obligation to stay the course.”

Bell’s legacy will live on in many ways at NYU Law, including through the two annual Derrick Bell scholarships for NYU Law students.

—