The Man Following the Money

A successful former prosecutor of international drug lords and white collar criminals, Neil Barofsky ’95 doesn’t scare easily. But can the special inspector general for the Troubled Asset Relief Program protect the public purse from Wall Street’s profiteers?

Printer Friendly VersionWALK INSIDE THE NONDESCRIPT RED TOWER on the corner of 18th and L in downtown Washington, D.C., and you will find two rent-a-cops standing guard in a lobby that wants to be impressive but doesn’t quite hit its mark. The security badges, rather than the architecture, give the only hint of the power residing within. They read “OFS,” for the Office of Financial Stability of the Department of the Treasury.

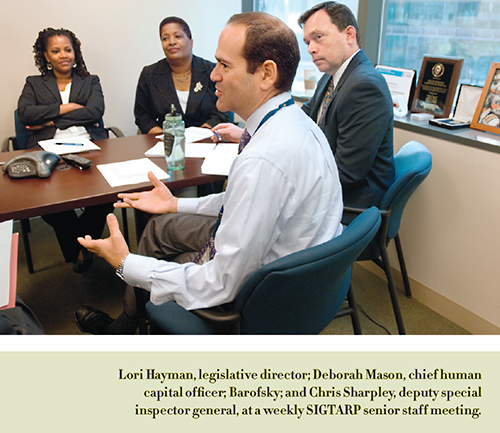

The atmosphere on the fourth floor isn’t much different. Low ceilings, high cubicle walls, and a deafening silence suggest the kind of action you might find in the quarters of a paper-pushing bureaucracy. It’s just the opposite, though: this is the office of the special inspector general for the Troubled Asset Relief Program, or SIGTARP, where a small number of government employees are doing their utmost to save the American people billions of dollars. And no one is working harder to that end than Neil Barofsky ’95.

Since his confirmation as the country’s newest special inspector general in December 2008, Barofsky hasn’t had much time to catch his breath. After spending more than eight years as a prosecutor in the United States Attorney’s office for the Southern District of New York, he was tasked by President George W. Bush with keeping tabs on what ultimately became a possible $3 trillion in disbursements under the TARP—better known as the bailout of Wall Street and the auto industry. It’s certainly the most ambitious undertaking the 40-year-old lawyer has ever tackled, and his focus is unwavering. While he has a corner office with a view, he still hasn’t had time to move in properly. His workplace has a not-quite-unpacked feeling, and even the framed copy of his presidential appointment leans on a window ledge, next to a signed photograph of New York Yankees legend Don Mattingly.

Dressed soberly in gray pants, a white shirt, and gray tie on one of February’s seemingly endless snowy days, Barofsky is remarkably subdued when explaining what it’s like to try to hold the most powerful people in U.S. finance to account, from banking CEOs all the way up to the secretary of the treasury and the chairman of the Federal Reserve. He seems unfazed by the act of speaking truth to power, but that’s not too surprising: he has faced far more terrifying adversaries than the pinstriped crowd—including drug smugglers known for disemboweling people who get in their way.

WELL BEFORE 2008, Barofsky already had an enviable résumé. A graduate of the University of Pennsylvania and the NYU School of Law, he had distinguished himself in the New York legal community as an excellent trial lawyer, taking on everybody from drug pushers to white-collar thieves. The way things were going, he might have been a candidate for U.S. attorney one day, or, at the very least, he was setting himself up for a cushy partnership in one of the city’s prestigious law firms.

And then came the financial crisis. Like many Americans, Barofsky has found his career inexorably changed by the near-meltdown of Wall Street and the global economy as a result of the bursting of the real estate bubble. But unlike the tales of a bunch of the erstwhile Wall Street masters of the universe whose flameouts were a spectacle for the ages, Barofsky’s story is that of a remarkable talent plucked out of relative obscurity at a desperate time.

When President Bush authorized Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson to start throwing mountains of money at the crisis—the TARP was initially conceived as a $700 billion bailout, and Paulson spent $125 billion in a single meeting with nine large financial firms—Congress had the foresight to create a position that would track just where the money went. The new special inspector general’s office would conduct, supervise, and coordinate audits and investigations into the use of TARP money. That’s when Barofsky first came to the attention of those outside the legal community in New York and Washington.

Working with a bare-bones staff—by May 2010, he had about 118 people working for him and had budgeted a relatively puny $48 million—Barofsky has shown a degree of productivity that boggles the mind. Since the start of 2009, his office has conducted nine audits of TARP spending (12 more are ongoing), launched dozens of investigations into potential fraud, and produced thousands of pages of reports to Congress.

What’s more, the tenacity with which Barofsky has stayed true to his stated mandate has resulted in a startling degree of public awareness of the results of the SIGTARP office’s work. The cover of each of its quarterly reports to Congress includes the tagline “Advancing economic stability through transparency, coordinated oversight, and robust enforcement.” There is progress on all three fronts.

When he testified before the U.S. Senate on February 5, 2009, Barofsky made it quite clear that his office would not rubber-stamp Treasury decisions when it came to disbursement and oversight of TARP funds. Whereas in the heat of the moment, Treasury had quite simply given hundreds of billions of dollars to the country’s largest banks with few restrictions on how that money was to be used, Barofsky signaled that he would insist on transparency, starting with the seemingly obvious request to banks that they provide details on what they planned to do with any funds they received. Remarkably, that was something Treasury hadn’t thought to ask.

“When I came on board on December 15, 2008, within eight days I made a recommendation that Treasury start requiring TARP recipients to report on how they were using the funds,” Barofsky said at the 2009 NYU Law Global Economic Policy Forum and Law Alumni Association Fall Lecture last November. “That recommendation was rejected by the Bush administration and has been rejected by the current administration. That has been indicative of a bad attitude toward basic transparency.” Barofsky has been a thorn in the side of both the Treasury and the Federal Reserve ever since.

But that’s part of the job. Another part: coordinating efforts with a veritable grab bag of other government bodies, from the Congressional Oversight Panel, headed by Elizabeth Warren, to the comptroller general of the United States (who is the head of the General Accounting Office), the FBI, and the Department of Justice. A recent inquiry into potential fraud surrounding Bank of America’s disclosures in the lead-up to its controversial merger with failing investment bank Merrill Lynch, for example, conducted in conjunction with New York State Attorney General Andrew Cuomo, resulted in civil charges being filed against Bank of America and its former CEO Ken Lewis in February.

Enforcement, by definition, has come last. Barofsky, who refers to his office as “the cop on the beat” for the TARP, has 105 open investigations as of July 2010 into potentially fraudulent use of TARP funds, but only a handful that have been successfully concluded. Barofsky doesn’t see anything wrong with that. “You can’t investigate a crime until it’s actually occurred,” he explains with a smile. “TARP only came into being in late 2008, so the majority of crimes we’re looking into occurred in 2009. Securities and accounting fraud cases also take a lot of time. We’re just getting started here.” A hotline to report fraudulent or wasteful use of TARP funds has received more than 10,000 calls as of May, leads from which have been behind some 27 investigations.

Despite the underwhelming office space, the insignificant budget, and the relatively new position in Washington’s power grid, Barofsky has, since the moment he became SIGTARP, had his voice heard as if he were one of those Looney Tunes characters speaking through a megaphone. (Or maybe a Fox cartoon: friends joke that Barofsky resembles Homer Simpson once his five o’clock shadow kicks in around noon.) But no one who knows him, from his family to law school professors and longtime colleagues, is surprised that he’s achieved so much in such a short period of time. It’s what he’s been doing his whole life.

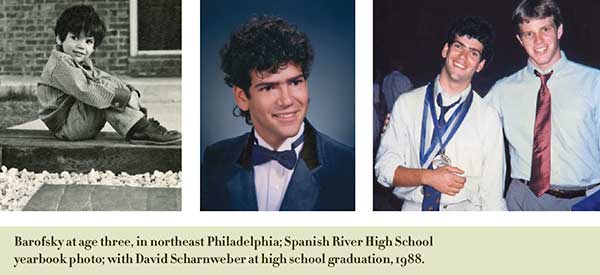

NEIL MICHAEL BAROFSKY was born in April 1970 in northeast Philadelphia. For the next 16 years, his would be a peripatetic life. His father worked in the travel business, which necessitated that the family—parents Stephen and Gail, and Neil and his two older sisters—move to Wyndmore, a suburb of Philadelphia, when Neil was three years old; to Scarsdale, New York, when he was nine; to Minnesota when he was 15; and finally, when he was 16, to Boca Raton, Florida, where Stephen and Gail opened their own travel agency.

While he says he had typical boyhood fantasies of being a fireman or a policeman when he grew up, Barofsky also remembers wanting to be a lawyer at a “ridiculously young age.” He says his mother still keeps the fortune from a cookie Neil opened when he was 12 that read, “You Will Be a Great Lawyer One Day.”

Thinking back, his high school friends recall clues that suggest the anonymous cookie fortuneteller was onto something. “Neil would always win the debate,” says David Scharnweber, a classmate at Spanish River High School who remains a close friend. “He could craft reasonable, compelling arguments from the very beginning.” (Barofsky says simply: “I had a big mouth as a kid.”)

It wasn’t only the teenager’s verbal skills that garnered notice. He was a standout in mathematics as well. Barofsky’s math teacher—and pal David’s mother—Terry Scharnweber remembers a precocious mind. “He always asked the questions that needed to be asked,” she recalls. “He took nothing for granted, always wanting to know what was behind the math.” (“I was a mathlete!” Barofsky says with a bashful smile more than two decades later.) He would take Advanced Placement classes and win a handful of regional academic awards in his two years in the Boca Raton school district.

This combination of verbal and mathematical fluency would put Barofsky in good stead to handle the intricacies of his position as SIGTARP—a job that quite literally involves sifting through mountainous volumes of numbers and then somehow translating the results into English.

Barofsky says there was more talk of sports around the family’s dinner table (he remains a fan of the NFL’s Miami Dolphins to this day) than there was about politics or social injustice. Still, 20 years before Bush would nominate Barofsky to the job of a lifetime, the high school senior would include “Republicans” in his list of dislikes in the school’s yearbook. “That will always haunt me,” he says, laughing, in 2010. “But I have overcome my dislike of Republicans. I count many as my friends today.”

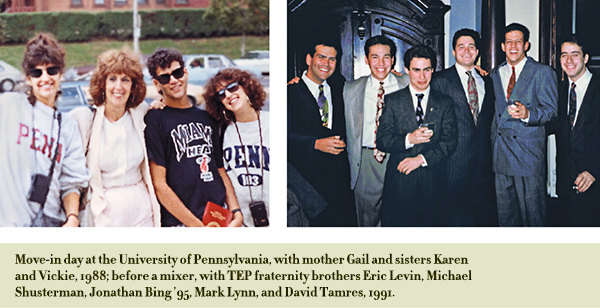

During his four years as an undergraduate at the University of Pennsylvania, Barofsky maintained his unrelenting work ethic. Penn is chock-full of Ivy League overachievers, but Barofsky managed to stand out even among those peers by earning a dual degree: a bachelor of science in multinational management, from the undergraduate division of Penn’s Wharton School, and a bachelor of arts in international relations.

Barofsky joined a fraternity—Tau Epsilon Phi, or “TEP”—and enjoyed Penn’s urban campus in West Philadelphia. Jonathan Bing ’95, a fraternity brother and later a law school classmate, says Barofsky “was pretty well destined to do something important and intellectual down the road.” Bing, now in his fourth term in the New York State Assembly representing the 73rd District in Manhattan, hastens to add, “He had fun and enjoyed college, but he was also pretty intense, even then.” Indeed: Barofsky graduated magna cum laude.

THE WHARTON SCHOOL supplies much of Wall Street’s white-collar labor force. Barofsky headed north too, but he entered NYU Law in the fall of 1992.

The decision to attend NYU, he says, came down to a combination of the reputation of the school itself as well as its location. “To be 22 years old and living in subsidized housing in the West Village…there’s nothing better than that,” he recalls. “Law students are neurotic people by nature, and it’s very easy to get sucked into the school, and your life becomes nothing but law and law students. That’s not the case at NYU. There’s just way too much going on around you.”

While he enjoyed and excelled in the majority of his classes—Barofsky graduated magna cum laude from law school too—one particular course comes to mind when he considers how NYU may have shaped decisions he made after graduation: Criminal Procedure, taught by Adjunct Professor Andrew Schaffer.

“[Schaffer] was one of the few professors at the time who were teaching with a pro-government stance,” Barofsky recalls. It was a controversial class, with Schaffer delivering a perspective of how the government managed to navigate around such hot-button issues as the Fourth Amendment, instead of the more typical perspective of how a defendant might use it to wiggle out of a legal corner. “Listening to his war stories, I remember thinking that this was the kind of thing I wanted to do,” recalls Barofsky. (“I tell my students every year that I am likely more pro-prosecution than all but about 10 of them,” laughs Schaffer. “It’s a good bet Neil was among the 10.”)

Barofsky did manage to find the time to enjoy what New York City had to offer, including taking in as many games as he could of his beloved New York Yankees. (He’d been a fan since moving to Scarsdale.) He maintained his allegiance to the Dolphins, however, and would brazenly cheer for them during their once-a-year pilgrimage to Giants Stadium to play the New York Jets. Along with classmate Jonathan Klarfeld ’95, now a deputy assistant director at the Federal Trade Commission, he attended the now-legendary 1994 game during which hall-of-fame quarterback Dan Marino faked a spike with just seconds left, caught the Jets’ defense napping, and threw a game-winning touchdown. “He was not a good sport that day,” laughs Klarfeld, a Jets fan.

He also fed an insatiable desire to see live music, his tastes in which run from classic rock—Barofsky is probably one of the few people working in the Treasury Department today who saw Pink Floyd play “The Great Gig in the Sky” at Yankee Stadium in June 1994—to 1980s new wave band Echo and the Bunnymen. His favorite? “It changes every day,” says Barofsky. “But right now, I’m back to the Clash, otherwise known as the Greatest Rock Band of All Time.”

IN JANUARY 2009, the New York Times referred to the office of the United State Attorney for the Southern District of New York as “one of the city’s most powerful clubs” and home to “perhaps the most prestigious federal prosecutor’s job outside Washington.” While some of the office’s assistants are hired straight out of law school, the bulk of them are plucked from the city’s elite law firms themselves. After graduation from NYU Law, Barofsky decided to take the latter route.

He landed a job in the litigation department at Weil, Gotshal & Manges. In short order, he was drafted to the legal team representing a number of cable television networks in a dispute over the appropriate rate they should pay the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP) for music licensing. While Barofsky and his colleagues were representing high-profile clients such as MTV Networks, ESPN, USA Networks, and the Disney Channel, he feared the case might overwhelm his early career and prevent him from building the résumé that would position him best for the highly coveted gig as an AUSA.

A colleague, Chris Morvillo, saw Barofsky’s frustration at not having an opportunity to work a wider range of cases and suggested that he speak to Morvillo’s father, Bob, one of the founding partners of white-collar litigation firm Morvillo Abramowitz. Both Morvillo and Elkan Abramowitz ’64 had worked in the Southern District office—first as AUSAs and later as chiefs of the Criminal Division—and the firm had a singular reputation as a kind of finishing school for those seeking admittance to the SDNY.

“These guys pretty much invented white-collar prosecutions when they were AUSAs,” says Barofsky. “And then they went on to invent white-collar criminal defense.” A job at Morvillo Abramowitz held not only the promise of experience on the kinds of cases that he wanted to work on but, of equal or greater importance, the possibility of a recommendation to the SDNY from legendary figures in the field. After spending just 14 months at Weil Gotshal, Barofsky decamped for Morvillo Abramowitz. (He may have been right about the ASCAP case as well: litigation dragged on for more than a decade.)

Barofsky got the immersion in white-collar litigation that he’d been looking for. An early case: In 1997 the firm acted as defense counsel for Josef Goldstein, son of the former president and owner of 47th Street Photo, who was charged with defrauding the highprofile electronics retailer’s creditors. Goldstein and three co-defendants decided to risk a jury trial. It was the wrong decision—all were convicted—but Barofsky remembers the six-week trial as a tremendous experience. “I learned a ton,” he recalls, “both during the trial itself and in the long lead-up to it, especially how to use the tools of federal criminal practice in a practical way.”

Barofsky worked alongside Abramowitz himself during the trial, handling a few witnesses and even arguing a motion. He impressed the partner with his fledgling courtroom abilities. “Neil had an ability to synthesize a ton of material and explain it to the jury in an easy-to-understand way,” recalls Abramowitz. “His verbal skills, in particular, were well beyond those of many of his contemporaries.”

Just a few years out of law school, Barofsky was already demonstrating a relentlessness that might be grating were it not for its lack of sharp edges. He was forceful but not quite abrasive, and the same holds true today. Barofsky is that guy—the one who some way, somehow, usually avoids being irritating, even when disagreeing with you.

After two and a half years apprenticing for the white-collar pioneers, Barofsky had gotten what he set out to obtain: the ability to think like a defense lawyer if and when he was putting together a criminal case from the other side of the courtroom. “Having that defense perspective, that ability to scope out the weaknesses in a criminal case, is an essential tool in the prosecutor’s toolkit,” he says.

“Neil came in more mature than many of the young lawyers we hire,” recalls Bob Morvillo. “He hit the ground running. While he was both careful and diligent, I think one of the reasons we recommended him so highly to the U.S. Attorney’s Office was that he was also creative. Give him a task, and he didn’t just give you back the four corners. He would give you the context in which the project should take place.”

In the fall of 2000, the 30-year-old was offered the job he’d been aiming at for almost five years: then-U.S. Attorney Mary Jo White named Barofsky an AUSA. He would spend more than eight years in the office—working under four different U.S. attorneys—and handle several extremely high-profile cases. He would also narrowly avoid being kidnapped and killed by narco-terrorists.

BAROFSKY’S TENURE AS AN AUSA started the same way as every other new assistant’s did: he spent a year in the general crimes division, dipping his toe in the prosecutorial waters and trying to learn as much as he could from his more seasoned colleagues. Along with his colleagues, Barofksy moved to narcotics in his second year. Like many who have trodden the same path, he found the action energizing enough that he decided to stick around, and he joined the International Narcotics Trafficking team.

Over the next three years, he would prove an aggressive lawyer, unafraid to bring charges or pursue a difficult case. Nor, for that matter, was he afraid to challenge his superiors. “He does what he thinks he should do even if it leads to clashes with those above him,” says Anthony Barkow, a former SDNY colleague and current executive director of NYU Law’s Center on the Administration of Criminal Law. “Still, those same people wanted him on their cases because of his tactical, strategic, and professional judgment.”

Sifting through the voluminous indictments, extraditions, and convictions that Barofsky and various colleagues successfully brought against drug smugglers of every stripe between 2001 and 2005 can cause one to revise one’s first impression of Barofsky. In person, he comes across as lawyerly, a little on the bookish side. What doesn’t come across, though, is how boldly and fearlessly he pursues criminals to bring them to justice.

He prosecuted heroin kingpin Ramiro Lopez-Imitola for importing more than 2,000 kilograms of heroin, worth some $200 million, into the U.S. Lopez-Imitola is the kind of guy who, when told that one of his drug mules has died in Miami, offers a henchman $10,000 to cut the body open and retrieve 88 pellets of heroin from his intestinal tract. Lopez-Imitola was sentenced to 40 years in prison.

But prosecutions against the likes of Lopez-Imitola were merely a warm-up to one of the most groundbreaking drug smuggling cases ever brought in a U.S. court: Barofsky’s investigation and prosecution of 50 leaders of Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia—known by their Spanish acronym, FARC—on seminal narcotics charges. The Department of Justice charged FARC with importing more than $25 billion worth of cocaine into the U.S. and other countries, and accused them of supplying more than 50 percent of the world’s cocaine. It was the largest narcotics indictment ever returned. “I think we redefined the FARC, which was one of our goals,” Barofsky later told the Washington Times. “The press stopped calling them freedom fighters and started recognizing them for what they are, which is one of the most thuggish, violent, narcotics cartels that’s ever existed.”

Richard Sullivan, then a senior AUSA and currently a judge of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, says what Barofsky was able to accomplish with the FARC prosecution was a show of dedication for the ages. “Main Justice had spent years trying to develop a case,” he recalls. “And we only got involved because agents and law enforcement in Colombia asked us to step in and make some headway. Keep in mind, if we were going to seek to extradite, we needed the strongest possible case. We couldn’t afford to swing and miss if the evidence fell apart. But Neil was able to accomplish in a couple of months what it had taken several years for people in Washington to not accomplish. It’s a great example of how he was—and is—willing to push people if they got in the way of what he thought was the right result.”

Over several months in the lead-up to the case, Barofsky and his partner Eric Snyder ’94 spent weeks at a time in Colombia, unearthing evidence that everyone knew was out there but that had yet to be put together into a coherent whole. A big part of the plan: trying to lure FARC defectors identified through a Colombian witness protection program called Reinsertado to come to the other side and testify about the organization’s crimes. One of the most promising witnesses was a high-ranking female who had corroborated a number of pieces of information and who had access to FARC’s senior leadership. She was so promising, in fact, that the U.S. team had identified her as one of the small number of cooperating witnesses to whom they would offer entry into the U.S. witness protection program in return for crucial testimony. It was a fortuitous decision.

Presented with this new future, the witness came clean and explained that she’d been operating as a double agent, telling her FARC bosses what she’d been asked by Barofsky and how she’d replied. More importantly, she revealed a plan to kidnap Barofsky at an upcoming interview, torture him for information, and likely kill him. (The original plan had called for the woman to detonate a bomb during her interview, but she’d refused.) “It would have been a great ‘get’ for the FARC to grab a U.S. prosecutor,” says Barofsky, somehow managing to consider the strategic implications before the personal ones. “But that was it; I didn’t go back after that. I’m not that brave.”

It didn’t matter; the work was done. On March 2, 2006, Attorney General Alberto Gonzales announced a one-count indictment charging 50 leaders of FARC with importing $25 billion of cocaine into the United States. The press release announcing the indictment mentioned contributions from the Department of Justice, the DEA, U.S. Immigration, the IRS, the FBI, the NYPD, the New York State Police, and the U.S. Marshals Service, as well as Colombian law enforcement. But Barofsky was the glue that held the case together.

Former U.S. Attorney Michael Garcia says Barofsky’s work on the FARC investigation firmly ensconces him in the SDNY’s lofty tradition of spearheading innovative federal litigation. “There are lots of great lawyers in the Southern District, so it takes a lot to stand out,” he says. “The way to do that is to be one of those people who can actually create a new case, a new enforcement initiative, or a new legal approach. That’s a rare quality, but Neil showed he had it when he pretty much created the FARC case. Those are the people who move the office. Those are the people who can conduct great trials. That puts Neil in a very select group.”

Barofsky’s main souvenir from the FARC days is an eight-inch bayonet knife given to him by local law enforcement with an inscription of one operational code name: “Bogotá 2007: Tango Chaser.” It is not, contrary to some published reports, the actual knife taken from a would-be assassin of Barofsky. Still, it’s a damn cool piece of office décor.

WHETHER HE’LL ADMIT IT OR NOT, Barofsky realized that narcotics wasn’t going to get any better than the FARC case, and in 2005 he transferred to the Securities and Commodities Fraud Unit.

It didn’t take long for him to end up at the center of another important case—the prosecution of several executives of the brokerage firm Refco for perpetrating a $2.4 billion accounting fraud. Along with colleague Chris Garcia, he deciphered an unusually complicated scheme in which Refco’s former CEO Phillip Bennett and one of its owners, Tone Grant, had, over a period of several years, masked hundreds of millions of dollars of losses through a series of sham transactions.

If Barofsky was already known for his dogged investigations and ability to work well both with internal teams and other law enforcement agencies, it was during the Refco trial that his courtroom abilities became widely appreciated. “He is a tremendous trial lawyer,” says Barkow. “He delivers his jury addresses, opening, closing, and rebuttal without a scrap of notes, which is very rare, particularly in complicated cases. His rebuttal in the prosecution of Tone Grant was probably the best one I have ever seen by a prosecutor.”

The compliments also come from the other side of the courtroom. Gary Naftalis, who represented Bennett in the Refco proceedings, also praised Barofsky’s performance. “It was a complicated whitecollar criminal case involving very complicated transactions,” he recalls. “He mastered those transactions and presented them to the jury in a very clear and understandable way. Everybody talks about all the glory of trial lawyers, but you’re putting in 10 hours out of court for every hour in. And it’s clear that Neil is getting his hands dirty outside the courtroom.”

“The experience of being a trial lawyer combines the best and the worst of the job,” says Barofsky. “As a prosecutor, it’s like an elaborate game of chess. Your work literally starts months before the first pretrial motion, and everything is designed six months or a year out for what’s going to happen in that courtroom. There’s nothing quite as gratifying as laying down a strategy—anticipating a certain defense, for example—and seeing it come into play a year later. At the same time, there’s the responsibility of it all. You can’t be wrong; you can’t be 99 percent sure that some person probably committed a crime. You might still get a conviction, but you still have to look at yourself in the mirror every morning. That’s a heavy burden.”

In October 2007, Barofsky was part of an SDNY team that won the John Marshall Award for Asset Forfeiture from the Department of Justice as a result of the Refco trial. Just over a year later, the DOJ again recognized the Refco team, giving it the 2008 Director’s Award for Superior Performance by a Litigative Team. That was just a few months after Bennett and Grant were sentenced to 16 and 10 years, respectively, for their roles in the fraud.

Barofsky thinks both were adequate sentences, but he does agree with the perception that the lack of a sufficient threat of jail time is a major contributor to the preponderance of securities fraud in the U.S. “I’m in the minority in being pro-sentencing guidelines,” he says, “and I do think the fact that they have been basically abrogated by the Supreme Court has meant that a lot of these white collar criminals don’t get the sentences they deserve. I’ll tell you what another problem is, though: Most people don’t get caught. It’s usually only during a financial crisis that a lot of these crimes get detected. It’s much harder to detect fraud when everything is going well.”

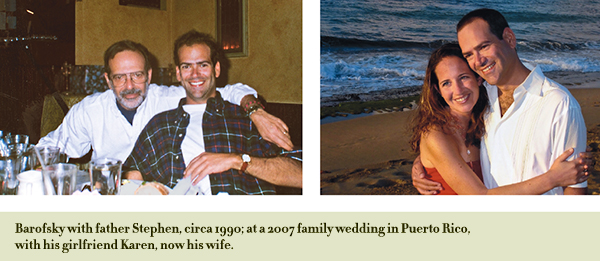

Speaking of going well, Barofksy was also thriving in his personal life at the time. He’d met a psychologist named Karen through an online dating service in March 2007, and was planning to ask her to marry him once the Refco case had wrapped up. On April 17, 2008, the decision came back on Tone Grant. While his trial partner was typing up the press release, Barofsky slipped out and picked up the ring. Like many a man with a ring in his pocket, he found it nearly impossible to concentrate on the celebratory drinks that evening, and at seven o’clock the next morning he asked Karen to marry him. Her verdict marked the second victory for Barofsky in as many days.

The couple planned to get married in Costa Rica in early 2009. It should come as no surprise, however, that the legally minded Barofsky wanted a U.S.-sanctioned marriage, and the couple decided to tie the knot stateside. Judge Richard Sullivan—Neil’s SDNY mentor—married the two on 8/8/08, a date chosen for the Asian superstition that eight is a lucky number. (Even lawyers can be superstitious.) They told no one of the secret nuptials.

UNITED STATES ATTORNEY GARCIA had seen enough of Barofsky’s tenacity and judgment to trust him with important cases. But in working with him on the Refco case, he also saw leadership traits. Turnover at the senior level in the Southern District doesn’t happen on a regular schedule, however, and while Garcia—now a partner at Kirkland & Ellis—had his eye on Barofsky for a senior position, none opened up.

A solution presented itself, however: in mid-2008, Garcia decided that mortgage fraud had become pernicious and pervasive enough that it was time to create a new mortgage-focused investigative group. He asked Barofsky to be in charge of it. “Neil took our ability to go after mortgage fraud to a whole new level, pretty much from a standing start,” recalls Garcia.

The group wouldn’t enjoy the fruits of Barofsky’s leadership for long, though. Just months after creating the group, Garcia received a call from the White House. The administration was looking to fill a new position as chief watchdog of the TARP, which would soon be disbursing money to banks at a disturbingly fast clip.

Did Garcia have anyone in mind, the White House wanted to know? Yes, in fact, he did. “The person I thought of immediately was Neil,” says Garcia. “Because it’s a really difficult role requiring a combination of attributes: good judgment, the ability to work with folks, but also the ability to push back. And while we know in hindsight some of the dimensions of the crisis, at the time we didn’t really know how things were going to break in terms of a possible meltdown in the markets.”

Taking the idea to Barofsky, Garcia decided to go with the hard sell. “Neil likes to say that I gave him the ‘God and country’ speech, and I did. I told him that it was a call to service at a historic moment. I told him that the country needed the right person in the role, and that I thought that he was that person. On a smaller scale, I’d seen him create an organization from scratch with the mortgage fraud group. I told him he had a chance to do it again, but this time on a humongous scale—to be the only watchdog, the only check on spending of hundreds of billions of dollars. Needless to say, he bit.”

Things proceeded quickly from there. Bush nominated Barofsky on November 14, and the Senate confirmed him on December 8. One glitch: During the confirmation hearings, Barofsky referred to his “wife,” Karen. One of his sisters, watching in Miami, turned to his mother and said, “What did he just say?” Numerous theories sprang up regarding Barofsky’s apparent slip of the tongue, all of which would be cleared up at their “official” wedding. The two would postpone their African honeymoon until May 2009.

A reporter for the New York Daily News tracked down Barofsky’s father for comment. “You should congratulate the country,” Barofsky the elder said. “He does his homework and his prosecutions speak for themselves. [But] I don’t envy him. It’s not going to be an easy thing.”

BAROFSKY ROLLED INTO WASHINGTON with a full head of steam, if not an actual office or employees to speak of. For the first several months, he barely saw his new wife, working from dawn until dusk trying to build a government agency from the ground up. Fifteen months later, he has succeeded in that goal, and his creation has been successful both in terms of its objectives and in terms of public relations measures. When Barofsky talks, Congress, the media, and the American people listen. “I sometimes chuckle when I think about it,” says Sullivan. “He was tailor-made for the job: so independent, so smart, so hardworking. The taxpayer is getting their money’s worth.”

That’s not to say that he hasn’t ruffled a few feathers along the way. When Barofsky is taking people to task, he rarely aims low. He has on several occasions lambasted Hank Paulson for misleading the American people about the health of certain banks—Bank of America and Citigroup come to mind—during the early days of the financial crisis, when Paulson claimed that every bank receiving the TARP’s initial disbursement of $125 billion was healthy. Both banks would require subsequent infusions of billions more to stave off collapse. The result of that disconnect, Barofsky says, is a level of cynicism among the public that could have been avoided. “He knew in his heart that they weren’t healthy,” Barofsky says. “And in the process, he created a sense that you can’t believe anything the government says.”

Barofsky has also chided the current treasury secretary, Timothy Geithner, taking him to task over what he considered misleading statements about the ultimate return to taxpayers for the $85 billion in government support of AIG. Over and over, he has criticized government officials for what he considers unnecessary and damaging obfuscation regarding the use of TARP funds, a position with which most major media organizations are in total agreement—thereby guaranteeing Barofsky a podium when he seeks it.

It’s ill advised to respond to such attacks publicly when someone has the moral high ground on their side, so there’s been nary a peep out of the Treasury Department regarding most of Barofsky’s barbs. That doesn’t mean that Treasury officials don’t get up to their usual Washington antics. In early 2010, a whisper campaign was apparently emanating from senior Treasury officials suggesting that Barofsky was planning to switch parties and run for state attorney general of New York as a Republican, thus explaining his attacks on Obama’s choice of Treasury Secretary. But such a theory ignores the patently obvious fact that Barofsky is and always has been bipartisan in his choice of critical targets.

Indeed, Barofsky understands that his job is not to make or to implement policy, but merely to keep an eye on those doing so with billions of dollars of taxpayer money. Still, he also understands the context of it all. “We talk about the costs of the TARP,” he told the NYU Law audience last November. “We can talk a lot about dollars and cents. And we can talk about the need for regulatory reform. . . . But there is a third cost: to the credibility of the government itself, which is one of its most important and necessary assets in dealing with a crisis. People need to trust their government. They need to be able to have faith when asked to come up with hundreds of billions of dollars. And the failures of transparency have had a dramatic impact.”

Interestingly, Barofsky comes across as more critical of dissembling public officials than of Wall Street itself. Indeed, he thinks bankers are doing as bankers are wont to do, and that if there’s any real tragedy from the crisis, it’s that policymakers may yet squander a perfectly good opportunity for meaningful financial reform. “It’s interesting to hear so many people say, ‘Wow, rather than accomplish our policy and societal goals, Goldman Sachs and these banks are using all this money to maximize their profit,’” says Barofsky. “What do you think happens in a capitalist society? What are these banks supposed to do? They are going to do what they do, which is to try to make profit. If you are going to push this amount of money out and not put any conditions on it, it just seems strange to me to be shocked and horrified by what is a very predictable result.”

BAROFSKY IS MORE OF A DOER than a talker, though, and those who know him best think the real action at SIGTARP is yet to come. He’s an investigator at heart, after all, and he promises that some of those 105 open investigations could be quite significant. The Bank of America charges were just the beginning.

“Unfortunately, history teaches us that an outlay of so much money in such a short period of time will inevitably draw those seeking to profit criminally,” he testified to Congress in February 2009. “One need not look further than the recent outlay for hurricane relief, Iraq reconstruction, or the not-so-distant efforts of the RTC [Resolution Trust Corporation] as important lessons.” A year later, he made clear what he considers the likelihood of uncovering fraudulent use of TARP funds: “The only government program that has zero chance of fraud or misconduct is a program that never gets run.”

Once again, he’s thinking like the other side: “Put yourself in a corporate fraudster’s mind. The $700 billion bailout of Wall Street was not only a financial bailout but also a potential fraud bailout. Anyone in the midst of perpetrating a fraud is always looking for the big cash out, the infusion that’s going to save you and get you out of the situation you’ve found yourself in. So let me be clear: If you think TARP money is going to be your way out, you’ve got another thing coming. And we’re not going to stop at banks that got TARP money. We’re going to be looking at those who merely applied for TARP money.”

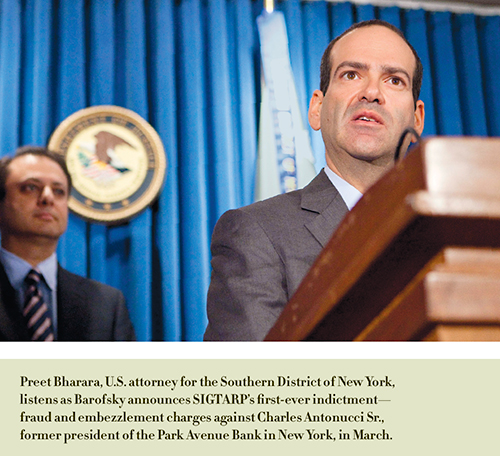

He wasn’t kidding. On March 15, 2010, Charles Antonucci Sr., the former chief executive of Park Avenue Bank in New York, was charged with trying to steal from the TARP by cooking the bank’s books—the first time criminal charges had been brought in connection with an attempt to steal from the program. It’s a point worth repeating: Park Avenue Bank never even received TARP funds. That didn’t matter; they tried to get their hands on some, and that put them in the SIGTARP’s sights. His accompanying statement on the day of the arrest was pure, no-frills Barofsky: “If you attempt to profit criminally from this historic program. . . you will be charged, and you will be brought to justice.”

Barofsky knows that his is a temporary job, even if it lasts another five years or so. At some point, after all, the TARP will be wound down, and there will be no more money left to track. What then? If it was hard to see him settling into a well-paying partner’s gig a few years ago, it’s even harder now. A civic-minded lawyer from the very beginning, Barofsky’s gotten a taste of what it’s like to make a difference on the biggest stage possible, one populated with actors like the president of the United States, the Congress, and the most powerful corporate interests in the country. New York attorney general might not be too far off the mark.

Before he dives headlong into the next gig, however, he and his wife are likely to step back and appreciate their most significant accomplishment yet: the birth of the couple’s first child—Zoe Ella—in April. Pointing to a picture of Karen scuba diving off Lombok, Indonesia, Barofsky sheepishly admits that he brought the underwater photo into the office when he realized that the only person he had a picture of was the Yankees’ Mattingly. And while he has spent a career doing things a little differently than those around him, it’s a good bet Barofsky will soon be acting like a typical new father. Which means Mattingly better get ready to share a shelf with pictures of a little girl.

—Duff McDonald is a contributing editor at Fortune and New York magazines. He is also the author of Last Man Standing: The Ascent of Jamie Dimon and JPMorgan Chase (2009).

—

All 2010 Features

All of 2010 Alumni Almanac

Multimedia

Multimedia