Pros in Con

NYU’s constitutional law faculty is asking rigorous questions about how to live today within a 228-year-old framework for our laws and democracy.

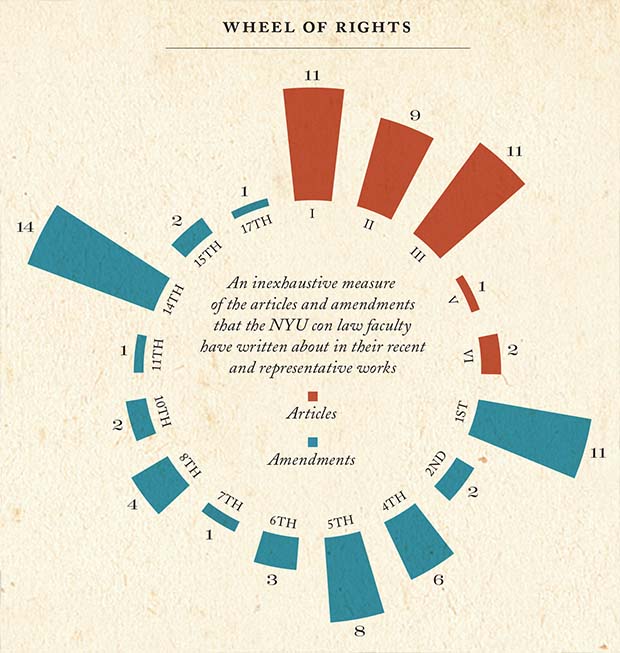

Printer Friendly VersionConstitutional law grapples with some of our most difficult—and consequential—legal, political, and social questions. The range and scope of these questions are extraordinary: individual rights; federalism and separation of powers; the limits of popular sovereignty; race and class; wartime exigencies; and voting, among others.

These questions sweep broadly and intersect with other substantive legal subjects. Indeed, the traditional law school curriculum incorporates analysis of constitutional doctrine into a number of its core subjects. Property law explores the Takings Clause; administrative law studies constitutional due process obligations; and criminal procedure applies con law—focusing just on the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Amendments—to the criminal justice system. Once you look closely, says Professor Samuel Rascoff, you see that “there’s con law lurking everywhere.”

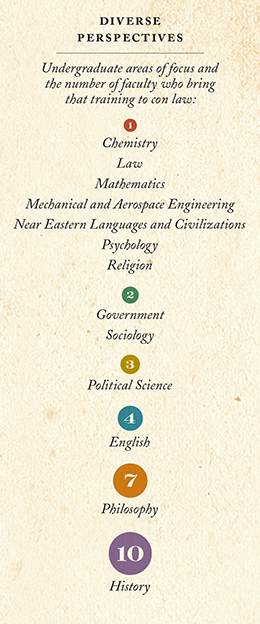

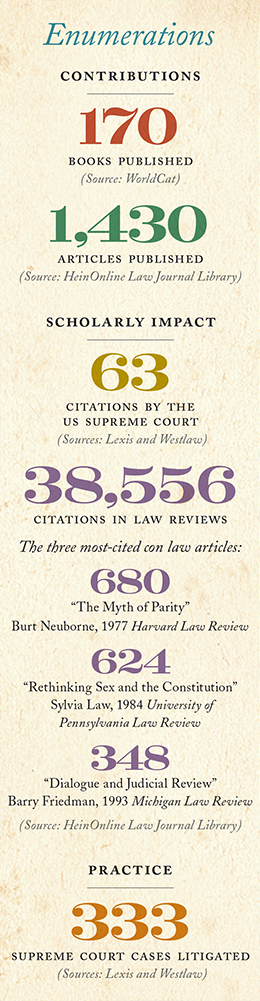

In recent years, the doctrinal and methodological boundaries of con law scholarship have expanded. Today’s scholars examine constitutional issues by way of traditional doctrinal methods of analysis as well as novel interdisciplinary ones that frequently employ methods of analysis from related fields such as political science, economics, history, and philosophy. “At NYU, we come at constitutional questions from a remarkably diverse range of perspectives,” says Barry Friedman, Jacob D. Fuchsberg Professor of Law.

Con law scholarship now accounts for more than a dozen distinct legal specialties at NYU. Some of these topics are completely new, while others would be familiar to a law student who matriculated decades ago—although contemporary research has pushed even the traditional fields in new directions.

Con law scholarship now accounts for more than a dozen distinct legal specialties at NYU. Some of these topics are completely new, while others would be familiar to a law student who matriculated decades ago—although contemporary research has pushed even the traditional fields in new directions.

Take, for example, property rights. Traditionally, scholars analyzed case law and related materials to determine whether a particular action constituted a taking or implicated a regulatory state issue. Contemporary scholarship goes further. In addition to analyzing doctrine, scholars today may incorporate economic and social science analysis to study “the incentive effects of government takings on property owners and investment” and how it might affect “the behavior and decision-making of government officials,” says Daryl Levinson, vice dean and David Boies Professor of Law. Similarly, the study of the separation of powers between the president and Congress now incorporates tools from political science. Rather than relying solely on traditional doctrine—the text of the Constitution and relevant precedent—scholars in this field now also understand that the checks and balances between these two branches are profoundly affected by political parties, in particular when one party controls both branches. Modern scholarship in con law, explains Levinson, considers “the problems that arise in the real world.”

The fact that President Obama had granted fewer pardons in his first term than any president since John Adams did not pass unnoticed by Rachel Barkow, Segal Family Professor of Regulatory Law and Policy (though she applauds his more robust clemency record in his second term). While clemency is enshrined in Article II of the Constitution as a core executive power, it is generally underused and applied arbitrarily. Barkow is bringing some discipline to the process by reimagining it as a constitutional authority to oversee federal prosecutors and correct disparities among them in how they charge cases. “There are no individual remedies available for disparities among federal prosecutors, and oftentimes clemency is the only corrective for mandatory sentencing laws that are overbroad,” says Barkow. “Clemency is a needed corrective on the criminal justice system.”

A critical problem with clemency, says Barkow, an expert in administrative and criminal law, lies in the institutional design of the process. The Department of Justice, as the agency that both prosecutes a case and then receives a request for clemency in the same case, has an inherent conflict of interest, she says: “Every request for clemency is at some level a criticism of the DOJ’s decision to prosecute in the first place.” Barkow, who serves on the US Sentencing Commission, advocates establishing a bipartisan commission independent of the DOJ that would make pardon recommendations to the president.

A critical problem with clemency, says Barkow, an expert in administrative and criminal law, lies in the institutional design of the process. The Department of Justice, as the agency that both prosecutes a case and then receives a request for clemency in the same case, has an inherent conflict of interest, she says: “Every request for clemency is at some level a criticism of the DOJ’s decision to prosecute in the first place.” Barkow, who serves on the US Sentencing Commission, advocates establishing a bipartisan commission independent of the DOJ that would make pardon recommendations to the president.

Not all con law specialties track traditional legal subjects. Events within the past 20 years have prompted scholars to develop new areas of inquiry. Three such areas stand out at NYU Law.

The law of democracy studies “the process of organizing democratic elections” and “the structures of democratic governance,” says Richard Pildes, Sudler Family Professor of Constitutional Law. Pildes co-founded the field in the mid-’90s with Samuel Issacharoff, Bonnie and Richard Reiss Professor of Constitutional Law, and Stanford Law Professor Pamela Karlan; the trio co-authored the first Law of Democracy casebook in 1998. They were motivated, in part, by then-current events, both foreign and domestic. Internationally, more new democracies were formed in the 1990s than in any comparable period, and at home the Supreme Court decided an important series of cases dealing with democracy-related questions about redistricting, term limits, and campaign finance.

These issues “emanated from the same foundational set of questions,” Pildes says, and the law of democracy “brought these issues together to examine them in a systemic way.” The field’s roots in real-life concerns kept it focused on how the institutions of governance actually functioned; scholars employed empirical tools from political science “to bring realism and the understanding of consequences to laws that regulate government processes and actors,” Pildes explains.

The brand-new specialty of global constitutionalism “would have been unthinkable prior to the ’90s,” says Mattias Kumm, Inge Rennert Professor of Law. It was during the ’90s that scholars first developed the precursor field of comparative con law—which compared and contrasted national constitutions—and from that scholarship emerged a new idea: “There were so many similar structural starting points” across “a range of constitutions governing liberal democracies” that, Kumm says, he and others began to “think of the shared principles” of human rights, democracy, and rule of law as part of a “mutually supportive and complementary” transnational enterprise.

The brand-new specialty of global constitutionalism “would have been unthinkable prior to the ’90s,” says Mattias Kumm, Inge Rennert Professor of Law. It was during the ’90s that scholars first developed the precursor field of comparative con law—which compared and contrasted national constitutions—and from that scholarship emerged a new idea: “There were so many similar structural starting points” across “a range of constitutions governing liberal democracies” that, Kumm says, he and others began to “think of the shared principles” of human rights, democracy, and rule of law as part of a “mutually supportive and complementary” transnational enterprise.

As political philosophies go, this was quite radical: Orthodox con law theory states that public laws are constitutionally legitimate if enacted by democratic systems operating through the sovereign state. The global constitutionalist idea Kumm helped refine held that national laws that span the national-international divide (for instance, climate change policy) cannot be legitimated by a single national polity. Rather, the constitutional legitimacy of such laws requires the integration of national and international legal systems—a topic scholars continue to explore.

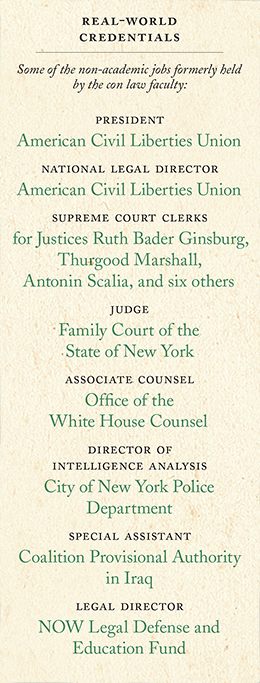

The US government’s implementation of counterterrorism policy in the years following the 9/11 attacks transformed national security law. A new wave of scholars shaped by experiences operationalizing counterterror strategies, including Dean Trevor Morrison (former associate White House counsel) and Samuel Rascoff (former director of the NYPD’s intelligence analysis unit), brought a pragmatic, policy-oriented focus to the field. Their analyses of frontier security issues drew on established legal frameworks and scholarly approaches from related disciplines; Rascoff describes his most recent article, concerning presidential oversight of the intelligence state, as “20-year-old political science and administrative law insight as applied to five-minute-old and into-the-future problems.” It is these kinds of inventive scholarly mash-ups that are key to bringing conceptual clarity to a field, Rascoff says, “dominated by a very-short-term focus on managing disaster and scandal, and its aftermath.”

Even the traditional is being studied in untraditional ways. Amy Adler, Emily Kempin Professor of Law, has looked to biblical times to explain why she thinks the First Amendment offers greater protection to words than to images (textual over pictorial pornography, for example). Her scholarship finds this preference rooted in ancient prohibitions on graven images and historical iconoclasm, and she concludes that jurisprudential assumptions about visuality have biblical rather than constitutional roots. Increasingly, Adler notes, this approach is in tension with contemporary culture, in which the image is emerging as the dominant mode of expression. “We—and particularly our students—live in an Instagram/Snapchat world,” she says, “one that First Amendment law has little to say about and is ill-prepared to address. My scholarship seeks to better equip scholars and jurists to address this new reality.”

Then there is the specialty of constitutional history, which has its own interesting history. Established in the late 19th century, the subject was out of favor for much of the next hundred years. But in the 1980s, high-profile legal conservatives started to discuss the “original intent” of the nation’s founders and proposed that the Supreme Court adopt “originalism” when interpreting the Constitution. Since then, a generation of historians—most of whom hold both law degrees and PhDs in history—have sought deeper, more nuanced, and more rigorous answers to questions of historical constitutional meaning.

Then there is the specialty of constitutional history, which has its own interesting history. Established in the late 19th century, the subject was out of favor for much of the next hundred years. But in the 1980s, high-profile legal conservatives started to discuss the “original intent” of the nation’s founders and proposed that the Supreme Court adopt “originalism” when interpreting the Constitution. Since then, a generation of historians—most of whom hold both law degrees and PhDs in history—have sought deeper, more nuanced, and more rigorous answers to questions of historical constitutional meaning.

Constitutional history first makes clear that “the constitutional project isn’t static,” says Daniel Hulsebosch, Charles Seligson Professor of Law. The story of the original Constitution and its modification— from the founding to adoption of the amendments through more recent changes to informal but important government practices—exposes “the gap between the simple framework of the Constitution and the complicated state we have now,” notes Hulsebosch. Contemporary constitutional historians scrutinize key Supreme Court opinions and the historical claims made by the justices in those decisions. The court’s opinions are often written in such a way as to make it appear that the justices are “restating received conventional wisdom,” explains Hulsebosch. In many cases, he adds, the justices are actually “making an argument about…what the Constitution should mean.”

Whether one adheres to the living Constitution or the originalist interpretation of it, the field of constitutional law is inarguably alive and growing. “NYU has a group of imaginative, innovative con law scholars working on some of the most vexing issues of the day,” says Larry Kramer, president of the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and former dean of Stanford Law School. Kramer, a renowned con law scholar who is a former associate dean for research and academics at NYU Law, believes the Law School’s scholars will continue to be a force in the field: “They have already helped shape how we all think about con law in a variety of areas and ways, and I expect them to continue to do so.”

—Craig Winters ’07 is the author of The Big Timers, a forthcoming book about the mutual fund scandal of 2003.

—

Related Link

“NYU Law faculty contribute to new Interactive Constitution”

NYU Law website, 9/21/15

—

Multimedia

Multimedia