Straddling the Thin

Blue Line

Amid a national uproar over police conduct, Brooklyn District Attorney Kenneth Thompson ’92 is working both to fight crime and to restore

public trust.

As a prosecutor for the Eastern District of New York in 1999, Kenneth Thompson ’92 was working on one of the most widely publicized cases of that time. A group of white New York City police officers had been charged in connection with the brutal beating and torture of a handcuffed black Haitian immigrant, Abner Louima, in a precinct bathroom. While Thompson was the most junior member of the trial team, senior prosecutors Alan Vinegrad ’84 (now a partner at Covington & Burling) and Loretta Lynch (now US attorney general) selected him to give the opening statement. “He had worked on [the case] since the beginning,” says Vinegrad. “Loretta and I thought that he deserved it and that he’d do a great job.”

The evidence offered plenty of material for Thompson to deliver an incendiary statement. Instead, the transcript shows a powerful but restrained presentation, in which his most dramatic declaration was, “Abner Louima was tortured in that bathroom, and his torture was cruel and it was simply inhumane.” In an era before cell phone technology made images of police brutality readily available, Thompson presented an unvarnished description of the violent assault. As the evidence mounted against the lead defendant, Justin Volpe, he changed his plea to guilty midway through the trial. He is serving a 30-year sentence in federal prison.

Today, Thompson is the Brooklyn district attorney, leading the third-largest DA’s office in the nation after those in the cities of Los Angeles and Chicago.

While Louima’s assault occurred nearly two decades ago, the case still encapsulates a complex reality that Thompson faces as a law enforcer, shaped by both personal and professional experience. The son of a police officer and graduate of John Jay College of Criminal Justice, Thompson has dedicated much of his career to crime fighting. As many initiatives of his current office demonstrate, his core mission is the same as that of the cop on the beat: getting the bad guys.

But through the Louima case and in other roles—including his current position—Thompson has also investigated ways in which law enforcers themselves may misstep, sometimes egregiously, and it has at times been his job to call them to account. It speaks to Thompson’s view of justice that he has made correcting past miscarriages of it—wrongful convictions—one of the top priorities for his office.

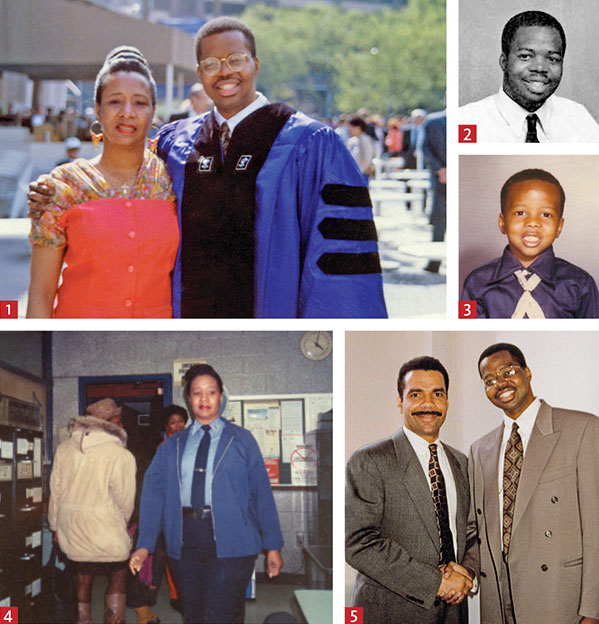

KEY MOMENTS: 1. NYU Law graduation, 1992; 2. NYU Law Picturebook, 1989-1990; 3. as a child, circa 1972; 4. Officer Clara Thompson at the precinct, circa 1985; and 5. With Ronald Noble, 1992

The charged mixture of race and police brutality in the Louima case also resonates today, as a series of police killings of African Americans has made headlines and provoked public outrage. Against this backdrop, Thompson’s dual role is cast in sharp relief. From Ferguson to Baltimore to New York, there is an urgent need for effective policing in minority communities heavily affected by crime. Every day, more than 500 prosecutors in Thompson’s office work hand in glove with New York City police officers to pursue the broad array of crimes that are the bread and butter of any prosecutor’s office in a major urban area. But in these same communities, some law enforcement tactics have severely eroded trust among the people the police are sworn to protect, and community members might see a DA’s office as both part of the problem and part of a potential solution.

“We have to do better in terms of the partnership that law enforcement has to have with the community,” Thompson says. “Thousands of people have been marching, including over the Brooklyn Bridge, and some of them have lost confidence in the criminal justice system, so we have to do more to improve that.”

Prosecutors and police chiefs around the country face the same challenge. As Brooklyn’s first African American DA, Thompson may face even greater pressure to restore trust between minority communities and the police. When asked about it, Thompson says that he “gets” the question, but deflects, saying he is the district attorney for all of racially diverse Brooklyn: “It is important for people in all communities to feel that law enforcement is there for them, not there to target them.”

KEY MOMENTS: 6. Courtroom sketch of Thompson as assistant US attorney in 1999, directing Patrick Antoine on the stand, with defendant Justin Volpe in the foreground and Judge Eugene Nickerson of the US District Court for the Eastern District of New York presiding; and 7. at Bronx Supreme Court in 2012, announcing a settlement between his client Nafissatou Diallo and Dominique Strauss-Kahn

Sitting in his office just blocks from the Brooklyn Bridge, Thompson exudes self-assurance. Tall and broad-shouldered, he dominates the expansive 19th-floor room from behind his desk. More than his physical presence, however, it is his baritone voice that draws the listener in. He speaks deliberately, with the thoughtful cadence of someone accustomed to choosing his words carefully. While he has the polish of a veteran politician, he has been in his first elected office for less than two years.

His journey to his current position began in a public housing apartment in East Harlem. The portrait of a young Thompson that friends, family, and colleagues paint is one of a serious person and an introvert who eschewed sports and hanging out in his neighborhood, preferring to read. His mother, says Thompson, was “the most important person who had influence on me.” One of the city’s first women to serve as a patrol officer, Clara Thompson had determination and a will to “always try to do something better,” as she puts it, qualities that transformed her family’s life.

Clara had worked as a nurse’s aide and in the post office when she took the newly gender-neutral civil service exam in the 1970s. She was assigned to a beat in the Bronx when Thompson was seven, and his memories of the era are vivid. She would put on her uniform at home, because female officers were such a novelty that there were no facilities for them at the precinct. Heading out to work each morning from the Senator Robert F. Wagner Houses in a police uniform was not for the faint of heart. “I don’t think people understand the weight of her decision, in ’73, to become a police officer,” Thompson says. “A black woman, living in the projects with three kids by herself; it was extraordinary.” She believed in herself, and her son was inspired. “If you want to trace what motivated me to go into law enforcement,” says Thompson, “it was my mother.”

Clara’s new career gave him a level of comfort with law enforcement alien to many other African American boys from the projects. “I grew up in the precinct,” says Thompson. Clara’s job also elevated the family’s finances. In 1974, she moved her family to the middle-class development of Co-op City in the northern reaches of the Bronx.

Thompson became the Daily News paperboy for his 26-story building and got to know many of his neighbors. He speaks fondly about growing up there. “It was a beautiful community for us,” Thompson says. The radical change in environment fostered the development of the studious and serious boy. “When all the other kids would be hanging out behind the building, he was never one of those kids,” recalls his mother. “He was always doing his homework, being by himself.”

Planning to follow his mother’s path, Thompson took the police entrance exam when he was 18. He scored 97 percent, in the top tier of thousands of applicants, but, since he wouldn’t be eligible to join the force until he turned 20, he began looking for other ways to pursue law enforcement. In 1985, he enrolled at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, a part of the City University of New York, and after graduating magna cum laude, he entered NYU School of Law in 1989.

During his third year of law school, he found the path he was seeking. An active member of the Black Allied Law Students Association, Thompson recalls that the arrival of Ronald Noble created a stir, particularly among the law students of color. Noble, who would go on to serve three terms as secretary general of Interpol—the first American to hold that position—was then a high-profile federal prosecutor who had been the president of his class at Stanford Law. Thompson signed up for Noble’s Evidence class, where he says he was “mesmerized” as Noble peppered his lectures with examples from his days as an assistant US attorney in Philadelphia. “He was so impressive and his work was so amazing; I knew from that point that I wanted to be a prosecutor,” Thompson says. “I wanted to be like him.”

During his third year of law school, he found the path he was seeking. An active member of the Black Allied Law Students Association, Thompson recalls that the arrival of Ronald Noble created a stir, particularly among the law students of color. Noble, who would go on to serve three terms as secretary general of Interpol—the first American to hold that position—was then a high-profile federal prosecutor who had been the president of his class at Stanford Law. Thompson signed up for Noble’s Evidence class, where he says he was “mesmerized” as Noble peppered his lectures with examples from his days as an assistant US attorney in Philadelphia. “He was so impressive and his work was so amazing; I knew from that point that I wanted to be a prosecutor,” Thompson says. “I wanted to be like him.”

In turn, Thompson made an impression on his professor, who recalls a focused and mature young man whose formal demeanor set him apart. Noble once asked Thompson whether he had a job to go to after class, because he was the only student who came to his class in a dress shirt, dress slacks, and a jacket. Thompson’s earnest answer was that he dressed to convey how seriously he took the job of being a law student.

The two got to know each other better when Thompson was selected to be one of two students on the admissions committee, on which Noble also served. It was during this time, Thompson recalls, that he told Noble of his intention to become a prosecutor and asked for advice about courses, internships, and jobs.

Through Noble, Thompson landed his first full-time job focused on criminal justice. Notably, it involved investigating a law enforcement operation that had gone awry. In 1993, the Clinton administration tapped Noble to review the siege of and assault on the Branch Davidian compound by federal agents in Waco, Texas, earlier that year. The operation had ended disastrously with the deaths of scores of people, including several federal agents. Noble—then assistant secretary of the US Treasury with oversight of agencies including the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms—reached out to his young protégé, and Thompson obtained permission for an early conclusion of his clerkship with Federal District Judge Benjamin Gibson in Michigan to join the investigative team in Washington as Noble’s special assistant. “Ken was the youngest guy on the team and the least experienced, but he established himself by being the hardest worker, with no task too small or beneath him,” says Noble. Thompson became the go-to fact expert. “You could ask him anything about agent X or Y, what he did, or document X or Y, and he would know it,” Noble recalls. The investigative report, delivered in 1993, was sharply critical of many aspects of the Waco operation.

Thompson then spent five years as an assistant US attorney in Brooklyn, working on an array of investigations and prosecutions of bank robbery, murder-for-hire, bribery, embezzlement, kidnapping, and other offenses, in addition to the Louima case. That was followed by 14 years in private practice, most of it at a firm that he and Douglas Wigdor formed to represent individuals in discrimination and civil rights cases. Here, too, Thompson handled cases that drew a media spotlight. One of their firm’s first cases was a 2003 lawsuit against Macy’s, alleging that those operating its private policing system engaged in racial profiling of suspected shoplifters. The suit claimed that Macy’s security personnel singled out Sharon Simmons-Thomas because she was black and detained her in a holding cell, where she was handcuffed and pressured to make a false confession, even though she had receipts for the items she bought. While the case settled for an undisclosed amount, it led to an investigation by Eliot Spitzer, then New York’s attorney general. Macy’s settled a complaint filed by the state for $600,000 and agreed to reform its in-store security practices.

No case drew Thompson more attention—and criticism—than his 2011 representation of hotel maid Nafissatou Diallo in her civil suit growing out of accusations of sexual assault by the then-head of the International Monetary Fund, Dominique Strauss-Kahn. Thompson stoked media interest in the case in ways that, critics said, ultimately undermined the Manhattan DA’s efforts to hold Strauss-Kahn accountable. Diallo settled her suit, and Thompson makes no apologies for how he handled the case, although he acknowledges that he might have done some things differently. “I had a woman who was in desperate need of a lawyer to protect her interests and who was going against one of the most powerful men in the world at the time,” he says. “She needed justice, and I fought to get her justice.”

Thompson had first introduced Diallo to the media at a highly orchestrated press conference at the Christian Cultural Center, a Brooklyn megachurch where Thompson has worshiped for the past two decades. Accompanying him were local politicians as well as the church’s pastor, Reverend A.R. Bernard, something of a political kingmaker (the pastor’s endorsement, reported the New York Times, was the first that Michael Bloomberg announced in his bid for a third term as New York City mayor). In that spectacle, some saw the beginnings of a campaign.

Thompson laughs at the idea that someone would take such a difficult case to set up a run for Brooklyn DA. His wife, Lu- Shawn, whom he met when they were both students at John Jay, says he had over the years occasionally talked about seeking the office. She would brush off the idea, worried that because he is “sensitive,” he would find the intense media coverage too grueling. But the crucible of the Diallo case, she says, changed her views. “They were attacking him pretty bad and it worked out.”

In his first-ever run for office, Thompson took on Charles Hynes, a 23-year incumbent as the Brooklyn DA. Hynes had seen his chances dwindle amid allegations of prosecutorial misconduct, abuse of power, and corruption. Thompson, meanwhile, attracted key backers, such as Brooklyn congressman and fellow NYU Law grad Hakeem Jeffries ’97, whom he had gotten to know when Jeffries interned in the US Attorney’s Office. They had bonded over shared backgrounds and priorities. “We both grew up in rough-and-tumble neighborhoods, and I think that has helped shape our experience and sense of social justice,” says Jeffries. Thompson’s campaign also drew on widespread popular support, including from many of the 37,000 congregants of Bernard’s church and from members of the powerful health care workers union.

Several attorneys who had opposed Thompson in court, including Willis Goldsmith ’72, also got behind him. Goldsmith, a partner at Jones Day in New York, remembers Thompson as the “voice of reason” throughout a contentious 2007 race discrimination case in which Thompson represented a black-owned business contractor against Goldsmith’s client, Verizon. Goldsmith, who won that case, later became friends with Thompson. He not only supported Thompson’s campaign, but also served on his transition committee. Thompson won the November 2013 election with 72 percent of the vote

Several attorneys who had opposed Thompson in court, including Willis Goldsmith ’72, also got behind him. Goldsmith, a partner at Jones Day in New York, remembers Thompson as the “voice of reason” throughout a contentious 2007 race discrimination case in which Thompson represented a black-owned business contractor against Goldsmith’s client, Verizon. Goldsmith, who won that case, later became friends with Thompson. He not only supported Thompson’s campaign, but also served on his transition committee. Thompson won the November 2013 election with 72 percent of the vote

When he took office in January 2014, Thompson quickly established a shift in tone and priorities. He beefed up resources and support for crime prevention and investigation, including by setting up Brooklyn’s first Crime Strategies Unit to curb high levels of gun violence in troubled neighborhoods. Staffed by senior prosecutors, the unit aims to identify people Thompson calls “the drivers of crime” and keep them off the streets. Unlike the NYPD’s controversial stop-and-frisk policy, the crime strategies approach targets known individuals—often gang members—believed to commit most shootings. “Whenever any of these guys gets arrested anywhere in New York,” says Thompson, “we get an e-mail and our criminal strategies folks spring into action to prepare the folks in intake in terms of what’s the appropriate crime to charge them with.”

The DA’s office is also keeping an eye on the supply side. In an effort to stop the flow of illegal guns into Brooklyn, Thompson and NYPD Commissioner William Bratton announced in April 2014 that, after a seven-month joint investigation, they were bringing a 558-count indictment against six firearms traffickers who were operating an “iron pipeline” from Georgia to Brooklyn.

Thompson also took long overdue steps, such as establishing a Forensic Science Unit. “How do we convict rapists and avoid convicting innocent people if we don’t have a dedicated forensic science unit?” Thompson asks. Another new unit—developed to tackle fraud against immigrants—had its genesis in the regular lunches he has with former Manhattan District Attorney Robert Morgenthau, who had created a similar unit in his borough. Thompson also gave four-percent raises to many of his prosecutors, some of whom were making less than $60,000 after five years as assistant DAs.

Even as he has moved to strengthen the crime-fighting capabilities of his office, Thompson has worked in tandem to check practices that he sees as undermining effective law enforcement, especially in minority communities, and to correct previous injustices. Three months into his term, for example, he alerted the NYPD that his office would no longer prosecute most low-level marijuana possession cases, noting that judges end up dismissing about two-thirds of such cases, and that he could not ignore the racial disparity in these arrests. Mayor Bill de Blasio later announced that the policy would be followed citywide.

During Father’s Day weekend this June, Thompson held the first of several planned Begin Again days, in which those with outstanding arrest warrants for minor infractions, such as drinking in public or being in a park after dark, can clear them through a pop-up legal advocacy and courtroom system in a neighborhood church. According to Thompson’s office, there are about 250,000 such open warrants in Brooklyn that are taxing an overburdened court system. More than 1,000 people arrived at the Emmanuel Baptist Church in Clinton Hill that day, and 670 warrants were cleared.

But the initiative that has brought national attention to Thompson’s commitment to the integrity of the criminal justice system, and not just the pursuit of lawbreakers, is his office’s devotion of enormous resources to the review of suspected wrongful murder convictions. He had campaigned on the issue, promising to rectify past injustices if elected.

Thompson brought in Ronald Sullivan Jr., faculty director of Harvard Law School’s Criminal Justice Institute, to co-lead a renamed and reconceived Conviction Review Unit (CRU), and provided it with a dedicated staff of 10 full-time prosecutors and three investigators. Of the more than 100 cases the unit has identified for review, 37 had been completed as of July 2015, and 13 of those defendants were found to have been wrongfully convicted, some after serving decades in prison. In recent months, Thompson has expanded the original scope of the review beyond murder convictions to include other miscarriages of justice, such as the case of Michael Waithe. Falsely accused and then convicted of burglary nearly 30 years ago, Waithe served 18 months in jail and faced deportation as a result of his conviction when he returned from his eldest daughter’s Barbados wedding in 2011. “That caused me to feel strongly that I can’t limit myself to homicide cases,” Thompson says.

All prosecutors have a duty to investigate claims of innocence or wrongful conviction, but in the vast majority of jurisdictions, that responsibility rests on the original prosecutor. The reviews often take a long time and the prosecutors, with full dockets of ongoing cases, don’t have a mandate to prioritize them, says Deborah Gramiccioni, executive director of the NYU Law Center on the Administration of Criminal Law and a former prosecutor. In Thompson’s office, however, the CRU makes recommendations to an independent panel. “Making a dedicated CRU shows that review is a priority of the office and therefore these investigations happen more quickly,” says Gramiccioni.

This streamlined process has been criticized by some involved in the original prosecutions who say they have not been given chances to respond. Such reactions are inevitable, says Samuel Gross, a University of Michigan Law School professor and the editor of the National Registry of Exonerations, a comprehensive online database: “It’s in the nature of this sort of review that some people will get rubbed the wrong way.” The process Thompson has established, says Gross, “is remarkable for the level of openness with which the work has been done.”

For Thompson, the unit’s achievements represent justice at its most fundamental. “The wrongful conviction work is very, very important to what I stand for as a district attorney,” he says. “I’m not interested in freeing murderers into the community, but we cannot allow innocent men, or men who were wrongfully convicted, to be in prisons for murders and other crimes that they did not commit.”

Among the police shootings drawing major headlines during the past year, one was on Thompson’s turf. Akai Gurley, a young African American man, was killed by an officer’s ricocheting bullet in the dark stairwell of an East New York public housing development last November. While a number of other recent high-profile police killings of black men did not lead to indictments, this one did: Thompson’s office has charged Peter Liang with manslaughter. The move was hailed by many as an overdue demonstration that “black lives matter”—a phrase that has gained currency around the country following incidents of police violence.

The public uproar over police use of force—and how to respond when it crosses the line—continues to bring added pressures to Thompson’s job. But even as he grapples with these issues, Lu-Shawn says, her husband remains fundamentally the same person she met years ago, down to the long hours he puts in at work and the music that blares out of his headphones. “That’s how he relaxes,” she says. Thompson acknowledges that he can be “too serious,” but close friends speak of his quick sense of humor and enjoyment of family time. And it is clear that the seriousness with which he has approached each chapter of his life has led him to exactly where he wants to be. From time to time, when Thompson has had a particularly hard day, Lu-Shawn asks him, “Do you like this job?”

The answer, she notes, never changes: “He always says he loves his job.”

—Aisha Labi is a freelance writer in New York City.

—

Multimedia

Multimedia