Dean of the Decade

In nearly every measurable area, NYU School of Law has thrived and grown under the leadership of Richard Revesz.

Printer Friendly VersionEarly last year, Richard Pildes, Sudler Family Professor of Constitutional Law, learned that his friend Robert Bauer, a confidant of President Obama and the White House counsel since 2009, was thinking of leaving that post. Pildes tipped off Dean Richard Revesz, for whom strengthening ties to the legislative and executive branches of government has been a high priority. (The era of focusing the Law School curriculum almost exclusively on the judiciary has ended on Revesz’s watch.) Within days, the dean had not only worked out a plan to persuade Bauer to choose NYU over the other top law schools that wanted him, but also had gone to Washington to close the deal.

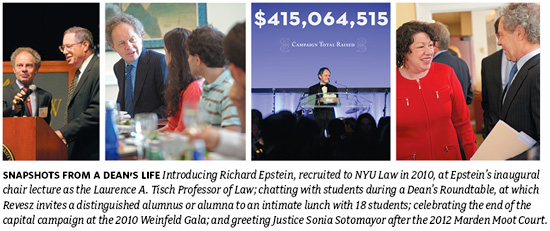

Bauer, now chief counsel to the Obama-Biden campaign, agreed to come to NYU School of Law as a senior fellow and adjunct professor. He has already shared his inside-the-Beltway perspective with students in seminars on presidential power and campaign finance, and he will continue doing so until at least 2015. “The picture Ricky drew overall of the Law School and its direction was compelling,” says Bauer. “He also made a powerful case for the excellence NYU had achieved—and that it would continue to pursue—in the fields of primary interest to me.” (Among other important Washington figures recently or currently teaching at the Law School, some on a fulltime or half-time basis, are C. Boyden Gray, White House counsel under George H.W. Bush; Paul Clement, solicitor general under George W. Bush; Sally Katzen, administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs in the Clinton White House; and judges Harry Edwards and Douglas Ginsburg of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, who both maintain senior status on the bench.)

With moves like these, Revesz has surprised even his most ardent supporters—who 10 years ago had no idea how big the job would become under his aegis. “The faculty was wildly in favor of Ricky becoming dean,” remembers Barry Friedman, Jacob D. Fuchsberg Professor of Law, who was on the search committee that recommended him to succeed John Sexton, now president of NYU. “But we knew there would be strengths and weaknesses. What’s interesting has been to see his strengths increase and his weaknesses kind of evaporate.”

One common perception was that Revesz—described by nearly everyone as brainy and hyper-logical—wouldn’t be good at motivating donors. “With that professorial look, he’s not the fund-raiser from central casting,” says Robert Kindler ’80, Morgan Stanley vice chairman and a Law School trustee. But David Tanner ’84, executive vice president at Continental Grain Company and now also a Law School trustee, says he hadn’t been a major donor until Revesz persuaded him to become one. “He has a wonderful way of making you feel like your philanthropy is really going to make a difference,” Tanner says, adding that Revesz “has no qualms about asking for big numbers.”

Very big numbers: Revesz has raised an average of about $50 million in each of his 10 years as dean, bringing his total so far to more than half a billion dollars. Despite the economic recession, he more than doubled the size of the annual fund from $3.1 million in 2002 to $6.5 million today and is building up the school’s endowment (still smaller than those of several rival schools). But sometimes, at a school Revesz describes as “entrepreneurial,” the endowment, which is composed of restricted funds, has to wait: Money, especially unrestricted funds raised for the annual fund, is needed to deliver student services, financial aid, and programs that, Revesz says, “help students and recent graduates do things they want to do”—including taking public interest and government jobs.

Very big numbers: Revesz has raised an average of about $50 million in each of his 10 years as dean, bringing his total so far to more than half a billion dollars. Despite the economic recession, he more than doubled the size of the annual fund from $3.1 million in 2002 to $6.5 million today and is building up the school’s endowment (still smaller than those of several rival schools). But sometimes, at a school Revesz describes as “entrepreneurial,” the endowment, which is composed of restricted funds, has to wait: Money, especially unrestricted funds raised for the annual fund, is needed to deliver student services, financial aid, and programs that, Revesz says, “help students and recent graduates do things they want to do”—including taking public interest and government jobs.

In fact, nearly every aspect of Revesz’s job has grown. Larry Kramer, until August the dean of Stanford Law School, says the responsibilities of law school deans have changed radically in recent decades. A dean was once primarily part of the faculty—a leader of the academic cohort. Then fund-raising and administrative duties multiplied, making the dean a veritable CEO. And NYU Law, which offers nearly a dozen joint-degree versions of its J.D., plus 10 LL.M.s and a J.S.D., is a particularly complicated organization to run, says Kramer, who was a vice dean and professor at NYU Law from 1994 to 2004.

Revesz is, by all accounts, a quick decision-maker once he hears the facts. And his door is always open, at least metaphorically; students and colleagues say he answers nearly every e-mail before the next day. Once, Revesz recalls, he got a 1:00 a.m. e-mail from a student who needed advice before a clerkship interview with Second Circuit Judge Guido Calabresi at 7:00 that morning. Revesz, who had studied with Calabresi at Yale, responded, and the student got the clerkship. Telling the story, Revesz says, “I remember thinking, This really is a fullservice operation.”

It’s tempting to think it was the chaos of his childhood in Argentina—which came only two decades after the decimation of his father’s family in the Holocaust—that fueled Revesz’s ambition. Each morning, Revesz remembers, he turned on the radio to find out if a coup or a general strike would make it impossible for him to get to school that day. (Because the heat in his apartment building didn’t come on until 8:00 a.m. and political paroxysms were frequent, Revesz says, it was rational to check the radio before deciding to crawl out from under the covers—a precocious application of cost-benefit analysis.) He chose the U.S., particularly Princeton, with its This Side of Paradise campus, as a refuge. After graduating summa cum laude, he went on to MIT for a master’s in engineering; his adviser suggested he round out his studies by learning microeconomics. That fomented his interest in public policy and a transition from engineering to law. From Yale Law School, where he was editor-in-chief of the Yale Law Journal, and a pair of prestigious clerkships for Second Circuit Chief Judge Wilfred Feinberg and Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, he arrived at NYU in 1985.

“Ricky is a great American success story,” says Raymond Lohier ’91, a judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. In fact, Lohier likens Revesz to Calabresi, former dean of Yale Law School (and, like Revesz, from a family displaced by European fascism).

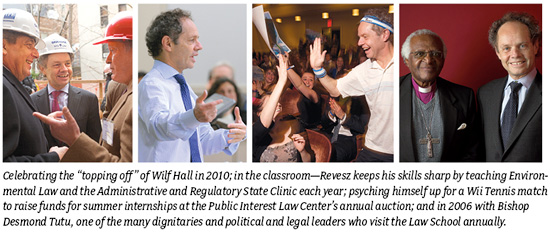

Like many ambitious deans, Revesz has made a tangible mark on his institution, building Furman Hall (which had been planned by Sexton) and Wilf Hall, acquiring 22 Washington Square North, and upgrading and modernizing the Law School’s cornerstone, Vanderbilt Hall. But he has made even more impressive changes to what happens in those buildings—including increasing the size of the full-time faculty from 83 to 109. Many of his 44 hires have been laterals from Columbia, Harvard, Michigan, and Chicago. The bottom line: Nearly half the current Law School faculty, including some of its biggest stars, has arrived during the Revesz era. “It’s been a singular focus of his,” says Kindler. “To get so many to come from Columbia and Harvard while losing very few to competitors is a very big deal.”

Revesz says he doesn’t rely on a checkbook to lure new faculty, explaining that NYU can’t afford to outbid schools with much larger endowments. Instead he appeals to a scholar’s desire to be part of a uniquely collaborative academic community that has an impact on the outside world. One Columbia professor, after meeting with Revesz, told the dean that it seemed the choice was between working alone in his office or joining NYU Law to work collaboratively; his eventual move downtown was another victory in legal academia’s version of the Subway Series. For those Revesz wants to entice from other cities, he has taken advantage of his simple observation that people often change jobs when their children are about to start elementary school, or just after their children finish high school—timing his recruitment efforts accordingly.

One of the results of the hiring spree, besides a faculty deeply loyal to the dean: There are now at least a dozen fields of law in which NYU arguably has the best faculty among the leading law schools. (Since Revesz became dean, this magazine has made the case for NYU’s preeminence in 11 of those fields.) But not content to merely hire leading academics, he exhorts them to do their best work after they arrive at NYU—one reason he personally moderates the weekly brown-bag lunches at which professors take turns sharing works in progress. His involvement, he says, helps keep research and writing on the front burner.

Revesz encourages professors to collaborate with students; he himself has had student co-authors on nearly all his recent publications, including his 2008 book, Retaking Rationality: How Cost-Benefit Analysis Can Better Protect the Environment and Our Health, co-authored with Michael Livermore ’06, now an adjunct professor at the Law School. The book lives up to its title, making a powerful argument for employing cost-benefit analysis—which, in Revesz’s view, had been co-opted by pro-business, anti-regulatory interests—in the service of environmentalism.

One reason Revesz seeks out student co-authors, he jokes, is that knowing a student is depending on him keeps him working when he might otherwise grab an extra hour’s sleep. But the real motivation, he says, is to give students an opportunity to share an experience he had at MIT, where his adviser made him feel, he says, like “a full colleague.” Even 30 years later his gratitude is palpable when he talks about it. That kind of interaction between students and professors is typical of Ph.D. programs but has rarely been available in law schools. In 2003, however, NYU Law launched the Furman Academic Scholarship Program. It is based on the graduate model, offering full-tuition scholarships, summer funding, and close faculty mentoring to a select group of students interested in academic careers.

The larger goal is to give all students interested in research the chance to do professional-level work, just as students in litigation clinics get to work on real (and sometimes important) cases. “You should think of your three years here as a time when you can accomplish significant professional things,” Revesz announces each spring at a breakfast for admitted students, who might have mistakenly thought law school was just for taking classes.

Matthew Shahabian ’11, now a law clerk to Judge Robert Katzmann of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, recalls speaking to Revesz about a subject of mutual interest: how discount rates, which are used to determine the present value of future benefits, influenced the perceived worth of various environmental regulations. At their first meeting, Revesz proposed co-authoring an article—“not,” Shahabian says pointedly, “that I be his research assistant.” From then on, he became accustomed to receiving comments and revisions from Revesz late at night. Eventually, Shahabian says, it dawned on him that at the same time Revesz was working on their article, “he was also writing another article with a friend of mine, teaching, traveling for conferences, meeting with donors….”

But Shahabian didn’t know the half of it. One way that Revesz has increased the complexity of the organization he leads is by adding a dozen academic centers and institutes that vary in the details but share the goal, he says, of getting professors, students, and professionals in the field “to work on topics of great legal or public-policy salience.” In 2008, the dean himself started the Institute for Policy Integrity, making his former student and collaborator Livermore the executive director.

And that’s just in New York; the dean’s portfolio includes major global initiatives, including a dual LL.M. degree program with the National University of Singapore Faculty of Law and a recently announced plan to give J.D. students semesters abroad in Shanghai, Paris, and Buenos Aires—the city Revesz left three decades ago.

At the same time, he has strengthened student opportunities to learn about the legislative and executive branches of government. Notably, he oversaw the addition of a required course on the Administrative and Regulatory State to the first-year curriculum, setting the stage for 2Ls and 3Ls to delve deeply into how Washington functions. He underscores the importance of this area by co-teaching, with Livermore, the Administrative and Regulatory State Clinic, in which students work with non-governmental organizations to prepare petitions, draft public comments for notice-and-comment rule-makings under the Administrative Procedure Act, and participate in administrative law litigation.

Mindful that many NYU Law graduates go on to work in corporate law firms or on Wall Street, Revesz has forged significant ties to the business community, taking advantage of resources that are available only in New York City. In 2007, the Law School launched the Mitchell Jacobson Leadership Program in Law and Business, which offers a J.D./M.B.A., mentoring, and a curriculum that includes a Business Law Transactions Clinic as well as roughly 10 “Law and Business of” courses—in investment banking, micro-finance, and bankruptcy, to name a few—co-taught by faculty from NYU Law and the Stern School of Business to students of both schools, who work collaboratively to analyze significant transactions presented by the principals who negotiated them.

Revesz has also made a considerable effort to support socioeconomically disadvantaged students, to diversify not only classrooms but also, eventually, law firm partnership rosters and corporate boardrooms. Last year, Sponsors for Educational Opportunity honored NYU Law for helping students from underserved communities succeed in college and the workforce. The Law School’s programs that support such students include TRIALS (Training and Recruitment Initiative for Admission to Leading Law Schools), a partnership with Harvard Law School and the Advantage Testing Foundation that offers LSAT preparation courses and other support; a five-week summer course in partnership with Legal Outreach to introduce middle-school and high-school students in underserved areas to careers in the law; and the AnBryce Scholarship Program—created by the chairman of the Law School Board of Trustees, Anthony Welters ’77, and his wife, Beatrice Welters, the U.S. ambassador to Trinidad and Tobago—which provides 10 full-tuition scholarships per class to outstanding J.D. students who are among the first in their family to pursue a graduate degree. “I truly believe in this approach to education,” Revesz says.

With all these initiatives and responsibilities, Revesz might resent the time spent on fund-raising, especially because there are no shortcuts—if he wants to raise twice as much money, he says, he has to make twice as many calls. But, in a typically Revesz-ian way of finding intellectual stimulation in jobs others might find tedious, he says he enjoys fund-raising because it introduces him to leaders in a variety of fields. Potential donors, he explains, tend to be innovators. Asked by a reporter why American universities are so much more innovative than their European counterparts, he responded that because leaders of U.S. institutions have to fund-raise, they need to interact with successful non-academics. As a dean, “you wouldn’t learn as much,” he says, “if you were just sitting around waiting for a big check from the government.”

Sitting around isn’t Revesz’s style. When he took the job, he had big shoes to fill. In 10 years he has not only filled those shoes, but used them to cover a lot of new ground.

—Fred Bernstein ’94, a journalist, clerked for two federal judges and now writes about his favorite subjects—including law, architecture, and fatherhood—for many publications.