Cops and Robbers: The Corporate Edition

Printer Friendly VersionThe international interest rate–rigging scandal currently ensnaring at least a dozen banks—and the fact that regulators might have known about it—stokes suspicions that corporate malfeasance is spinning out of control. This spring, the Law School magazine invited 10 distinguished faculty and alumni representing corporate defense, regulators and prosecutors, to discuss fraud, corruption, and bribery, and how to fight it. Rachel Barkow, a criminal law expert, moderated the discussion that appears here in condensed and edited form.

RACHEL BARKOW, Segal Family Professor of Regulatory Law and Policy (moderator): One of the signs at Occupy Wall Street protests said, “We’ll know corporations are people when Texas executes one.” That’s a pretty good sentiment for how corporate America is viewed right now. And so what this panel is going to talk about is whether that’s a fair characterization, what is the scope of corporate malfeasance, what’s the right level for government to be addressing, what are the real wrongs that are out there. There’s no shortage of statutes aimed at targeting corporate wrongdoing: the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, Sarbanes-Oxley, Dodd-Frank. Yet the FBI has reported that corporate fraud is on the rise. We have more prosecutions for foreign bribery. And in the wake of the financial crisis, many are asking questions about the conduct of players on Wall Street. So, Kathryn, suppose the president wants to know what, if anything, the government should do differently to combat corporate malfeasance. What would you tell him?

RACHEL BARKOW, Segal Family Professor of Regulatory Law and Policy (moderator): One of the signs at Occupy Wall Street protests said, “We’ll know corporations are people when Texas executes one.” That’s a pretty good sentiment for how corporate America is viewed right now. And so what this panel is going to talk about is whether that’s a fair characterization, what is the scope of corporate malfeasance, what’s the right level for government to be addressing, what are the real wrongs that are out there. There’s no shortage of statutes aimed at targeting corporate wrongdoing: the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, Sarbanes-Oxley, Dodd-Frank. Yet the FBI has reported that corporate fraud is on the rise. We have more prosecutions for foreign bribery. And in the wake of the financial crisis, many are asking questions about the conduct of players on Wall Street. So, Kathryn, suppose the president wants to know what, if anything, the government should do differently to combat corporate malfeasance. What would you tell him?

KATHRYN REIMANN ’82, Chief Compliance Officer, Citibank NA and Citi Global Consumer: I am not a sociologist or criminologist, but I do have a lot of practical experience in large corporate organizations with respect to culture and combating malfeasance.

When you talk about corporate fraud, you need somebody who is both motivated and, on a moral level, open to doing this kind of an activity. You need the opportunity and you need their assessment of what’s the threat or exposure to them. One thing that makes fraud in the context of any large organization, including government, particularly difficult to deal with is that when you talk about opportunity, unlike many other kinds of crimes, the opportunity often isn’t fleeting; it develops over time. Somebody comes in day after day, learns the system, learns the people around them. They know what the flaws are, they know where to exploit. The opportunity is continually there, the temptation is continually there, and they have the time to really get good at what it is that they’re going to do.

One thing that militates against commission of a crime is your perception of the victim. In corporate fraud, not only is it sometimes difficult for people to conceive of a victim, but also, if you view the victim as either not going to experience a harm or as perhaps having somewhat unclean hands themselves or in some way owing you or the public something, that, coupled with the opportunity, is going to put you in a situation where it’s much more difficult to combat fraud. From this perspective, I don’t think we need more legislation; we’ve got a lot right now that does speak to governance and basic controls, which are very important in preventing fraud. But we need to build the right culture, step up awareness. I would suggest that the government consider awareness campaigns in partnership with business that look for ways to set good civic examples, good cultural and governance examples that make people aware that fraud hurts them as well and that build a culture where everybody’s looking for this.

BARKOW: Harry, I assume you’re going to go right for it and say to the president, “I want your ear.”

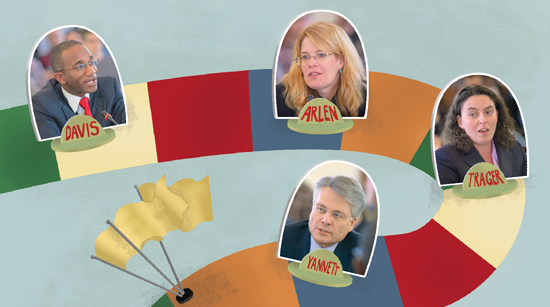

HARRY FIRST, Charles L. Denison Professor of Law: I’m tempted, but I’m going to go for a law enforcement response. There used to be a place near the Law School called the Lone Star Cafe that had a huge slogan: “Too much ain’t enough.” This applies to prosecutions for corporate fraud. Too many prosecutions is not enough. I would look for ways to go after all those malefactors. Here are three.

First: individuals. Government prosecutors need to make a greater effort to go after higher-level managerial officers. Prosecutors prefer to win cases, so they’re cautious about going after managers where they might not have so much direct proof that they actually knew about things, but who should have known about things. There’s law to enable prosecutors to reach such conduct, and we need to go after higher-level people as a matter of deterrence.

Second: corporations. Many of us are familiar with the deferred prosecution agreements (DPAs) and non-prosecution agreements (NPAs) that have become very popular and useful tools for prosecutors. The Justice Department should be a little more cautious in the way they’re used. Particularly NPAs. When corporations are willing to give up lots of money in return for a letter that says we’re not prosecuting you, it’s very tempting. But it’s troubling. We need criminal prosecutions against corporations. DPAs at least have a criminal complaint filed.

Third: better mechanisms for getting those people inside to rat out their co-conspirators. Tools that can get information to prosecutors are really important. We should have amnesty from prosecution, not just leniency. You get off in return for turning others in. This works really well in crimes of conspiracy and has been used to extraordinary effect in the antitrust area. There are other areas in which it can be used and other tools that prosecutors can think of because if there’s one thing prosecutors generally don’t have, it’s the information that people inside know. To get that information is really important.

BARKOW: All right. I want to hear from a defense lawyer perspective. Bruce, do you think we need more snitching and more cooperation? Why are the incentives not sufficient right now to do that? Or are they?

BRUCE YANNETT ’85, Partner, Debevoise & Plimpton: Now that Harry can’t give me a grade, I can get away with saying at the start that there’s nothing that Harry just said that I agree with.

Look, there are plenty of incentives for people to come forward, and prosecutors do give people amnesty. They do enter into agreements whereby in exchange for information, they agree not to bring charges. A good defense lawyer with someone who has significant information will work hard to negotiate something. And Dodd-Frank, which we are just beginning to feel the effects of now, provides substantial financial incentives for people to rat. They can recover up to 30 percent of what the government recovers if they report to the SEC. Since the law took effect a year ago, the SEC has seen an explosion in whistleblower complaints, very often drafted by plaintiff lawyers and very often 15 to 20 pages long with exhibits attached. Not crazy handwritten, Martianslanded- on-top-of-Citibank kind of letters. The incentives are pretty substantial for people to come forward; we don’t need more.

On the deferred prosecution agreements and the non-prosecution agreements, Harry said that NPAs are used too often, and basically companies can buy their way out of problems. I will agree that they’re used too often—but for the opposite reason. What happens is that the government decides they don’t really have a case. Because if they really had a case, they’d either be talking about a deferred prosecution or an indictment. So it makes it too easy for them because the company wants to put this behind it. For its employees. For its shareholders. For a million reasons. Rather than put the government to its proof and attack a thin case, they’ll agree to an NPA.

I actually disagree, though, with the opening premise that corporate fraud is on the rise. What you’ve got is flavors of the month. I’ve been practicing in this area now for 25 years, and we’ve seen different waves of fraud. There’s been healthcare fraud, there’s been accounting restatement fraud—and now we’re dealing with the mortgage and banking fraud. I can assure you, five years from now it will be something different. And it’s not that any of those are increasing or decreasing materially; it’s certain things coming to light and the government deciding to allocate resources to attack that problem.

BARKOW: So maybe we should hear from the government, because you’re getting beat up a little bit, Sanjay. What do you think: Does the government need more tools? Do you have what you need?

SANJAY WADHWA (LL.M. ’96), Associate Regional Director for Enforcement, Securities and Exchange Commission: To your original question about what would I ask the president, I, too, have three items on my list: money, money, money. If you could only see the circumstances under which the government or the SEC operates, with limited resources, where we are pressed in terms of human capital, technological capital, and investigating and then prosecuting wrongdoing by corporate America and folks associated with it, you’d be struck by just how much of an imbalance there is. Anyone who’s served in the government at any time in their career knows what I’m talking about. So…resources. That’s what we need.

I don’t know if corporate fraud is on the rise. I am a practitioner, so I only see what I see. Last year we brought a historic number of enforcement actions—over 730—which was significantly higher than in years past.

Just to deviate a little bit, my group has been working for the last five years on the Galleon insider trading investigation involving Raj Rajaratnam and now the expert networks, and what we’re seeing is this shockingly poor culture of compliance at hedge funds, mutual funds, exchange-traded funds. Folks at companies are essentially just selling confidential company information when they moonlight as consultants to hedge funds. Hedge funds then trade on it and make millions. I don’t know what companies are doing to prevent this culture, which is really viral, from spreading in their corporation. We have employees from just about every tech company out there—prestigious and highly reputable American corporations—who have been implicated in the expert networks matter. It’s no different than backing up a truck to the loading dock, stuffing it with stuff you’ve pilfered from your employer, and then taking it out into the marketplace to sell it.

In terms of senior officers, look, Rajaratnam was the co-founder of Galleon. We’ve brought about 95 enforcement actions concerning the financial crisis, and we’ve named 50 or so CEOs and CFOs, but I don’t know if anybody at this table necessarily knows that. An SEC action is not nearly as sexy as a DOJ action with the handcuffs and the spectacle of a criminal trial. The Journal and the Times and other such publications aren’t reporting this. But the fact is that we are continuing to bring significant enforcement actions at an increasingly rapid pace, and that has been the case for the last couple of years.

BARKOW: Among the business community, are people more aware of the increased enforcement?

WADHWA: I should hope so. But we’re also not in the business of publicizing. We make our statements through our enforcement actions, and if the message is not being absorbed by compliance officers and general counsels and other legal officers at big companies, that’s really something that they need to fix. It’s not something that we can fix; the message is out there.

BARKOW: So, Sara, what’s a good corporate officer to do to try to improve the culture?

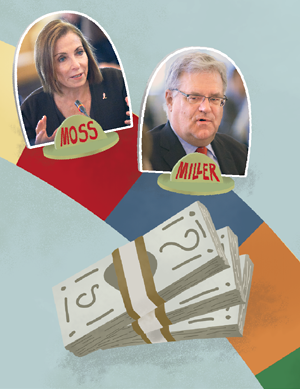

SARA MOSS ’74, Executive Vice President and General Counsel, Estée Lauder Companies: I’m certainly aware of the enforcement actions, but there have been enforcement actions for years. On prosecutions and SEC actions, it really is putting your fingers in the dike. There will never be enough resources to prosecute everyone. People will find ways to get around the rules. And there will be rogue employees, there will.

SARA MOSS ’74, Executive Vice President and General Counsel, Estée Lauder Companies: I’m certainly aware of the enforcement actions, but there have been enforcement actions for years. On prosecutions and SEC actions, it really is putting your fingers in the dike. There will never be enough resources to prosecute everyone. People will find ways to get around the rules. And there will be rogue employees, there will.

But going back to talking to the president: Why are there not incentives for companies that have outstanding compliance programs? We have the Federal Sentencing Guidelines for corporations; it lays out the factors for a robust compliance program. As the chief legal officer, I make sure we have a robust compliance program. And that includes a code of conduct, consistent enforcement, modules that people have to answer. Tone at the top is critical, and we try to make it vibrant and real and have people understand that it’s their obligation to protect the company and the shareholders from wrongdoing. Their job includes doing the right thing. I hadn’t thought about it in this way until you asked us to talk to the president, but it would be a lot cheaper, more effective, and a lot more positive to reward companies that have a robust compliance program and have not had problems.

WADHWA: Isn’t the lack of a reputational hit itself an incentive for companies to have robust compliance cultures?

MOSS: Sure. But how many do you actually hit? It’s like when instilling in children the difference between not getting caught and doing the right thing.

FIRST: Do you pay your children when they do well? What more incentive do you need than that the company doesn’t get into trouble?

MOSS: Maybe the government gives you a gold star.

FIRST: Usually we try to control ourselves; self-control comes at some cost to all of us.

YANNETT: But the fundamental difference—and I’m going to join with my colleague Sara—is for corporations, the strict application of respondent superior. I mean, if one of your kids hits the kid next door with a stick, you don’t get arrested for assault with a deadly weapon as the parent. If somebody on the NYU faculty assaults a student, the entire school doesn’t get shut down and prosecuted. You can have a fundamentally good company that takes compliance deadly seriously and have employees who do stupid things.

BARKOW: One underlying premise with what you are saying is that we can scratch the surface and figure out which compliance programs are real and which ones are not. How do we tell?

MOSS: There are auditors and people in the government who sit inside banks, and they know. You take the factors, for example, of what constitutes a real compliance program, and you talk to people. You look at the internal records of what the company has done when they find wrongdoing. Maybe I’m wrong, but I think you can determine that.

REIMANN: But think about Enron. Enron actually won an award and recognition for their compliance program and corporate culture right before the implosion.

As I listen to what everyone’s saying, one thing we get back to is leadership. I’m glad to hear the number of prosecutions that have been brought against Galleon and the like. Entities like that, where the people at the top have become engaged in something that is wrong, are not just corporations anymore. They’re criminal enterprises, and people do what they’re rewarded to do from the top of the house. You can paper over a compliance program as much as you’d like to, but if there is that at the core in leadership, if people are committed to a course of conduct that violates the law, there’s no compliance program that’s going to save you. What we’ve got to do is figure out a way to be vigilant and to find those places where leaders of companies are doing wrong. It’s very powerful when you can punish somebody who is sitting at the helm. There’s been a lot of research in this area.

Corporations where the CEOs are bullies or exhibit some very manifest behaviors that are not good leadership behaviors, there’s a tie between that and a bad culture. What we’ve got to think about and what I would also suggest to the president is these people come from somewhere, and building up civic awareness, starting even at the school level, will help you generate people who are thinking about these things and who can look for them and who place some value on governance and culture. As an employer, you want to have people who are discerning about the kind of company they’re joining. There isn’t a silver-bullet answer for that question. But it permeates this whole discussion.

BARKOW: So let’s get the law-and-economics perspective on this. The economists don’t love culture as the necessary factor, but what’s the right approach to target the bad apples? Assess compliance programs?

JENNIFER ARLEN ’86, Norma Z. Paige Professor of Law: In order to deter corporate crime, we need to reward companies that have good compliance programs, self-report, and cooperate, and we have to punish the individual wrongdoers. But we need cooperation from the corporations. Corporations can help or they can make it nearly impossible to get the needed information.

Historically, we held corporations strictly liable for corporate crimes committed in the scope of employment. This was a terrible approach because it discouraged firms from detecting and self-reporting their employees’ wrongs. After all, why would a rational firm detect and report a crime if this will just result in it getting convicted and punished?

So I support rewarding “good” companies by allowing those who self-report and cooperate avoid formal conviction. But they still should pay a monetary penalty in order to induce them to want to deter future crime.

To induce firms to help us go after the individual wrongdoers, we can threaten substantial criminal penalties if they fail to cooperate, and offer a DPA or NPA if they do cooperate. One advantage of the DPAs and NPAs is that we can exempt a firm from prosecution but still impose a substantial monetary penalty on the firm. You need firms to pay even if they do everything right to make sure that shareholders do not profit from the crime and that managers want to intervene ex ante to deter the crime, even if they expect that the firm will get credit for cooperation should a crime be detected.

I teach corporate governance, and I’m fascinated by the collision between the worlds of corporate crime and corporate governance. In corporate crime we’re worried about compliance. In corporate governance we sing the praises of high-powered incentives. We want managers whose pay goes up in the good times and plummets to poverty levels in the bad times so they’ll work hard. Yet anyone who knows about compliance knows that the evidence shows that short-term, high-powered incentives dramatically increase the risk of corporate crime. So if we are seeing more crime it is likely that it is arising out of this movement in the corporate governance world to enhance the high-powered incentives without any real recognition that there’s a serious downside combined with a bad economy: Bubbles create crime.

BARKOW: How much is the financial crisis tied to fraud and criminal activity or some kind of corruption at banks? We have monitors of banks—how come they couldn’t catch some of this? Geoff, what tool kit do they need in order to do a better job?

GEOFFREY MILLER, Stuyvesant P. Comfort Professor of Law: I don’t think the financial crisis caused misbehavior in banks. Nor did misbehavior in banks cause the financial crisis. The financial crisis was caused by something else, which was the tremendous amount of readily available cheap credit during the decade of the 2000s, which caused a housing bubble and many activities by firms, banks, and others that were highly risky. So the financial crisis was ultimately caused by cheap credit, and the chief culprit for the cheap credit is Alan Greenspan. I would recommend that, Sanjay, you go after Alan Greenspan for having caused most of the problems that we have now. Just kidding.

If I was talking to the president, I would say look for yellow flags. That is, look for things that indicate a possibility of fraud. And you’d use that to try to optimize your surveillance strategy to look for where fraud is. One of those indicators is cheap credit. And that happened in the 2000s, and there were plenty of people who took advantage of that. Also, a company that’s growing very rapidly is a sign of fraud. If you see a company where an insider or small group of people dominate and others don’t really know what’s going on, that’s a sign of fraud. If you see companies where people manipulate political connections a lot, that’s a sign of fraud. If you can’t quite understand the nature of the business, that’s a sign of fraud. If you see a company that has extreme operational complexity—Enron being an example—that’s a danger sign. If you see a company that tries very hard to manage its image, that’s a sign of fraud. By the way, Enron did that to an extreme; that’s why they won all those awards. I would direct my prosecutorial resources to companies that displayed those yellow flags.

Now, one last point—Berkshire Hathaway displays all the yellow flags of fraud, but I doubt that Berkshire Hathaway is committing fraud. So these yellow flags are only an indication, not a definite conclusion as to the presence of fraud.

REIMANN: If you think about the insider trading scandals and the housing market and the current debacle you’re dealing with, one thing that stands out is these are not instances where it was just a company committing the fraud. You have a variety of people who all have come to accept a level of behavior. Insider trading is a great example. From the hedge funds involved in it to the folks sitting in other companies who might have been issuers, to the fact that how long did it take Congress to kind of admit that, gee, maybe we shouldn’t be able to trade on insider information? Some of this passing of information just became accepted practice. The housing market—you had easy credit and people who found it profitable to let that easy credit roll on. You had people who applied for credit and because they didn’t need to give documents, they lied about their income. And then you had people who did appraisals and, well, everybody else was looking the other way, why not lie about the appraisal as well? There were colluding forces here, and if you want to get to the bottom of this, you have to figure out how corporations and others interact in these situations.

BARKOW: So, Mara, as I was listening to the yellow flags, I actually was wondering who was left, because that actually did strike me as all of corporate America. What are you doing at Civil Frauds to detect the good apples from the bad apples?

MARA TRAGER ’98, Assistant U.S. Attorney, Southern District of New York, Civil Division: My office, meaning the U.S. Attorney, has made civil fraud enforcement a priority. That’s reflected in part with the formation approximately two years ago of the Civil Frauds Unit that almost exclusively handles affirmative cases. In addition, there are many AUSAs in the Civil Division who have primarily defensive dockets who are also handling affirmative fraud cases. Since the formation of the Civil Frauds Unit, we filed over 20 lawsuits and have obtained judgments of almost half a billion dollars. In general, the cases that we’ve brought include mortgage fraud cases, fraud involving healthcare providers, procurement fraud, grant fraud. The Civil Division enforces the False Claims Act, which provides for treble damages, plus penalties when there is submission of false or fraudulent claims where federal funds are being used. And we also have been making greater use in recent years of the Antifraud Injunction Act. In terms of yellow flags that Professor Miller mentioned, he’s given us a lot of directions to go in potentially. The whistleblowers were mentioned earlier today, and whistleblower provisions are extremely important—certainly a lot of our cases stem from whistleblowers.

BARKOW: So one statute that you didn’t mention that also takes us a little more globally is the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. Let’s talk a little bit about bribery. Our focus has been individuals in a company who engage in either criminal activity or civil violations, either to profit themselves or to gain recognition within their corporation. The bribery context is different, because companies may say that the kinds of things they’re doing in other countries is the cost of doing business in a global environment. So, Kevin, what should we be doing on a global level?

KEVIN DAVIS, Vice Dean and Beller Family Professor of Business Law: Just dealing with corporate misconduct on the national scale is challenging enough. Listening to all the domestic issues that have come up, I was thinking those are really tough questions. We don’t know what the problem is and we don’t know how to respond to it. The issues are even more challenging when you start to think about them on a global scale. Even in terms of do we know if foreign bribery is on the rise. Yes, we’ve got more enforcement actions, but we’ll never know if there’s been more or less corruption over the past few years. I suspect it’s been about the same. And I would guess that on account of all the FCPA enforcement that corporate America is probably somewhat less corrupt these days. We can never do enough, but we’re probably doing something. Given the recognition that it’s impossible for the United States to be the policeman for the globe—we’re not going to clean up corruption in Nigeria, right? We’re not going to clean up corruption in Afghanistan—because we can’t do it in New York or Chicago.

So that’s not on the table. We have to figure out what the priorities are, figure out what the purpose behind the statute is, and then decide how to move forward. The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, as I understand it, is to try to prevent the United States or U.S. corporations from contributing to corruption in foreign countries. To prevent their governments from being undermined, to prevent development from being compromised, to prevent the United States from being embarrassed. Well, are we going to go after low-level bribery? Are we going to worry about people paying bribes to evade customs duties? That may not be such a high priority compared to the big bribes to obtain contracts for mobile phone systems. We can set priorities in terms of the type of misconduct. We can also focus on particular countries, the kinds of countries that need the most help from us. Some countries have their own anticorruption agencies that are more or less capable of dealing with these issues. But the Haitis of this world may not. Then we also have to figure out some new tactics. If the idea is to actually help these foreign countries, then we should think about helping them financially. $1.6 billion in the Siemens case went to the German government and the U.S. government and stayed there. Didn’t go to all those countries around the world that were actually the victims of the bribery. So we should give more thought to things like restitution payments for either the governments or particular groups within the foreign countries that are affected. And also think more about cooperation with foreign actors. This is also something we haven’t had to think about on the domestic side so much. Cooperation with foreign regulators, figuring out who prosecutes, what happens if one country wants to provide leniency, another one doesn’t. Working out all those issues should be a priority for us in the FCPA area as well.

BARKOW: This roundtable is presenting more problems than solutions. Bruce, you worked on the Siemens case, and I’m curious about how multinational corporations navigate a global regulatory environment where they can find themselves being prosecuted or charged in multiple jurisdictions. What are the pitfalls for companies? What are the kinds of things that companies have to think about going forward?

YANNETT: I headed up the audit committee investigation to figure out what happened at Siemens, and we were dealing with 14 separate government investigations around the world. It’s a real challenge. One of the things that we accomplished in Siemens really for the first time in a significant case was we were able to, over time, develop trust with the German prosecutors. We had the trust of the SEC and Justice Department. They know we’re going to do a good job and an honest job. But in fact, in most of Europe, companies do not hire lawyers to get to the bottom of things; they hire lawyers purely in a defensive mode. Here we’re showing up saying no, our job is, on behalf of the audit committee, to find out the truth and they’re like, yeah, right. It took a long time to overcome that initial distrust. We were able, though, by the end of the day, to get both the Germans and Americans talking to one another, meeting together, coordinating, so that the penalties were actually announced on the exact same day at the exact same moment and were totally coordinated. The multicultural differences, from a law enforcement standpoint, are enormous in terms of the Fifth Amendment privilege: Does it exist, does it not exist? Does the attorney-client privilege exist or not exist? Data protection laws: Here, if I do an investigation for a big company, there are effectively no limits on what I can look at, and in Europe there are all kinds of legal restrictions on what data you’re allowed to look at and what the company is even allowed to keep. You’ve got, in the U.S., employees at will, so if they do something wrong, Sara or Kathryn can fire them tomorrow. In places like France or Italy, there are very strict labor protection laws, and you may have to negotiate with the union. So the complexity is enormous.

The issues that Kevin was addressing and that your question brings up is not so much how do you deal with it once it hits the fan, if you will, but how do you deal with it from an operational standpoint and trying to operate a compliant business on a global basis? I’m the last person at the table who’s naïve, but most Fortune 100 U.S.-based companies have people like Kathryn and Sara who are genuinely committed to trying to instill a good culture. Companies spend tens of millions of dollars a year just on compliance and, yes, they’re going to have bad people. We all do. So for them the challenge is how do we compete in Africa against the Chinese when the Chinese don’t prosecute these things internationally? They prosecute their own people for corruption, but they’re literally bringing suitcases full of cash into Africa for the natural resources—something that used to happen in the West but is way, way down. The level of corruption is probably fairly static. Just the bribers have changed over time. It was the Americans and then it was the Europeans, and now even they’re getting serious about enforcement. So it’s the Russians and the Chinese now. And if the enforcement by the U.S. authorities against the American companies is so tough and they go after the $50-customs-agent-fee kind of situation, what it does is, if you’re in Sara’s position as general counsel of a big global company, you may decide, you know, Vietnam is a really hard place, it’s just not worth it, so we’re going to pull out of Vietnam because the corruption is so high. If the American and Western European companies pull out of Vietnam, who’s there? And has the corruption problem gone down or up?

BARKOW: I have found a silver lining, which is that this is all good for lawyers. There’s a need for good lawyers to ferret out fraud, bribery, corruption, and to do the compliance work. To do the auditing. And then to do the defense work if companies find themselves charged, and to bring the actions on behalf of the government. But what happens when we find somebody who is the bad actor, the bad corporation, the bad individual? What’s the appropriate sanction in this context? What’s the right hammer to throw at the problem?

REIMANN: Well, within the realm of a corporation, it’s critically important that whatever compliance program you have, that your disciplinary program enforces it in a very evenhanded and obvious way. There are activities where no matter who it is, who’s caught doing them, they must and need to be fired. And not permitted to resign. Some activities have to be fireable offenses, and people need to know that. That shows people that you’re serious and starts building a culture and shows through example how a good leader leads—which is that you don’t tolerate certain things. One of the issues in these fraud bubbles we’ve talked about is that the environment has just become too tolerant and permissive for that activity. If people are going to get slapped on the hands, then it sends the message that this behavior is really not so bad.

MOSS: I would agree, but I would go a step further. Criminal prosecution of the individuals is an important tool. I’ve referred a number of employees for criminal prosecution. These have not been bet-the-company kinds of things, but I would do that anyway. That sends a very important message. If there’s criminal wrongdoing, there should be criminal prosecution. I’m not saying there should not be sanctions and fines. But certainly criminal prosecution should be a tool. Financial fraud is very serious, and when it is committed against us or our clients, criminal prosecution is warranted. It’s the lesser offenses where companies tend to be lax in discipline, and they don’t view firing as that kind of a tool.

ARLEN: There is a role for DPAs and NPAs to impose structural reform sanctions. Most frauds by publicly held firms are agency costs—they’re done by managers for themselves, not for shareholders. In some cases, the agency costs not only cause the crime to happen but also undermine managers’ response to news that a crime occurred: Managers do not report the crime because they benefit from it. In this case, sanctioning the firm will not deter the crime, because the sanction falls on the shareholders. You need some mechanism for reducing those agency costs that affect corporate compliance, self-reporting, and cooperation. When we have those agency costs, it can be helpful to use DPAs to mandate compliance programs structured to reduce agency costs—for example, with chief compliance officers who report directly to the board. You also may need a mechanism to ensure that the firm adopts the program. That was the idea behind the corporate monitors. You could have reporting requirements or you could have civil oversight, but you need some kind of oversight mechanism.

We started out with this revolution in DPAs and NPAs where we impose compliance programs and then had monitors, and we now are moving into a world where we impose these compliance programs on firms as part of DPAs and NPAs and then not have any monitor. The DPAs and NPAs are changing. We’re not doing enough to make sure that companies genuinely comply. We’re not using the DPAs and NPAs enough to indirectly penalize the people responsible for why the firm had bad compliance or didn’t investigate.

We also are not using DPAs to help shareholders oversee managers. The statements of facts in the DPAs and NPAs say whether the firm had a good compliance program or not. But the DPAs rarely identify the managers whose actions caused the prosecutor to conclude that the firm’s compliance program or cooperation was deficient. If shareholders had more information on who within the firm was involved in having the noneffective compliance program, you would see some pressure brought to bear on those people either to do a better job or exit. We’re not using the disclosure tools available to the government to harness the monitoring of the market.

BARKOW: Sanjay, can you give us context to the broader criticism about the SEC accepting settlements without any admission of wrongdoing aside from just monetary fines?

WADHWA: You’re talking about Judge Rakoff’s decision in the Citigroup proposed settlement. It’s not just the SEC; every federal agency does this “neither admit nor deny” in its settlements. At some level it’s just practical. We don’t have the resources to litigate everything on every matter, and the neither-admit-nor-deny allows a company to settle with us while protecting itself from flank attacks in the private litigation arena. When Citigroup is ready to pay $285 million and they say we’re neither admitting nor denying, it’s a little simplistic to say they’re doing it because they want to get this behind them. There is something there. That was what we argued before Judge Rakoff. He doesn’t think it’s fair, he doesn’t think there’s enough transparency there. But we’re fairly comfortable that we’re going to ultimately prevail because we are an independent agency, and our take on the matter needs to be respected by the judiciary to a large degree. Judge Rakoff is making his points, but I don’t think he’s got the law on his side.

At the conclusion of the discussion, there was just enough time for the moderator to take questions from a student in the audience.

ALEX GORMAN ’14: Regarding having incentive for good compliance programs: In the manufacturing world there are ISO standards, which are best practices, and if you meet that standard you then have access to certain preferred government contracts and private contracts. So perhaps if you can put together some sort of gold star for good compliance, then maybe the premium on the stock price or access to preferred contracts could act as some sort of affirmative incentive for change.

MOSS: Shareholders and investors really care, for example, about environmental issues. There are all sorts of gold stars or gold standards. The government cares about it, but also investors care about it. We have reports on what we do environmentally; we don’t on corporate governance. But you would think that investors and shareholders would care about that. Look at Avon—that’s had a huge impact on the company. It’s a good point.

GORMAN: What is the role of private party litigation and how that fits in? What is the role vis-à-vis government enforcement mechanisms?

BARKOW: Kevin, is private law sufficient? A good complement? Sanjay’s already brought up the point that the neither-admit-nordeny language is really designed by agencies to protect a company from mass-action lawsuits. But how should we think about private litigation more broadly?

DAVIS: Ideally it would complement, but the problem is it’s impossible to coordinate all these different types of sanctions that can be imposed on a company because often you have to worry—at least in the FCPA context—not only about shareholder litigation and litigation coming from competitors who lost out because you paid a bribe; you also have to worry about debarment. The federal government could bar you from doing business with them going forward. This is possible not just in the U.S., but with the international financial institutions, in the European Union, elsewhere. Contracts might be canceled. There’s a lot that can be done on the private law side to sanction firms for engaging in all sorts of misconduct. The problem is we don’t know if all that will add up to the right level of sanctions. To echo what Jennifer was saying, it’s important for the government to at least try to target their sanctions, focus on the individuals or the group who is engaged in wrongdoing to the extent possible. Because what is the point of a few hundred million dollars in penalties for Citibank?

ARLEN: When we talk about the need to punish the firm with private sanctions, we don’t always distinguish adequately in the type of crime. It’s one thing to impose a sanction on a firm for an FCPA violation where the firm probably profited from it. But private sanctions in the area of financial misstatement securities fraud are a terrible idea. Private liability on individual managers is a great idea if they committed the fraud. But private corporate-level sanctions for securities fraud imposed on corporations have very little deterrent effect. Moreover it punishes the victims twice, because most securities fraud involves lying to the market so that people buy into the firm at an excessively high price. When the fraud is revealed, the market price plummets, both because of the truth and the anticipation that the firm will bear private liability. One of the things that Judge Rakoff completely missed about the SEC’s policy when it applies to financial misstatement fraud is that you want to disable the class actions as applied to corporations and force plaintiffs to go after the individuals. Do private sanctions complement public enforcement, or are they just another way of victimizing the people who were victims of the crime originally?

FIRST: Private-actions remedies are very complicated, and we’ve got lots of different possibilities. We didn’t mention putting people in jail, which is a really good remedy, and then that raises the question of for how long. But for private remedies to have a deterrent effect, they must also provide compensation to victims to incentivize them to sue. One of the problems is separating that out. It looks a little different in these fraud cases than in antitrust cases where you can very well have victims who need compensation and deserve it, like consumers, and that may have a deterrent effect, but it also has a very important compensatory effect. In fraud cases there is a problem even in thinking about who was hurt and who was helped, because the shareholders are a floating bunch. People who were helped may already be out of the stock by the time the suit is brought. And that’s also true for the financial penalties. If they’re ultimately paid by the shareholders, that’s not a fixed set of people. These difficulties may lead us, in certain kinds of cases, to look for other things like the monitors.

Debarment has pluses and minuses. It can actually lead to distortions in the food and drug area, where the debarment is for Medicare and Medicaid, which the pharmaceutical companies don’t very much need. We have to really think hard about that.

One area in which debarment could be used more is individuals rather than corporations. If you debar a corporation, you actually may end up hurting unintended victims like consumers who lose a product. Whereas if individuals for a period of time either can’t be rehired by their company or have to be in a different business, that may actually be a very useful and targeted penalty. The remedies issue is very important, and you do have to consider the effect of private rights, but we also shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that the remedies are not just for class-action plaintiffs’ lawyers, but are mainly for the victims.

BARKOW: Thank you all.

Note: The views expressed by Sanjay Wadhwa and Mara Trager are their own and do not represent those of the SEC or the U.S. Department of Justice.