Post-9/11, clinic students serving immigrant clients must practice creatively.

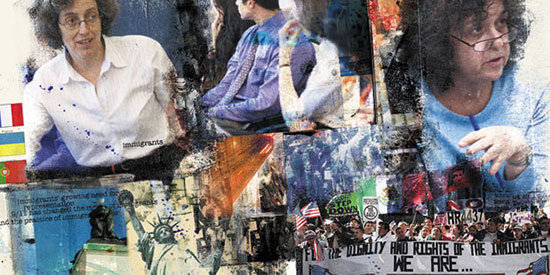

The United States deported about 208,000 individuals in 2005, 38 percent more than in 2002. The surge is one indication of the new challenges facing immigrants in this country, and their growing need for legal representation. “September 11 has changed the rights of immigrants and the practice of immigration law,” says Professor of Clinical Law Nancy Morawetz ’81, who directs the Immigrant Rights Clinic.

It has also deeply influenced the students who represent immigrants. In 2004-05, an unprecedented four Immigrant Rights Clinic students argued three cases before the court of appeals, opposing the deportation of long-standing legal U.S. residents. “The opportunity to tell my client’s story in court was both terrifying and empowering,” says Angelica Jongco ’05, whose client, Luis Gutierrez, had been deported to Colombia but, after her appeal, was granted habeas corpus relief. She is now a law fellow with San Francisco’s Public Advocates firm. Kathryn Ann Ruff ’06 and Peter Hartley ’06, who took the Civil Legal Services Clinic cotaught by Clinical Professors of Law Paula Galowitz and Lynn Martell, were so dedicated to their client’s cause that they gave up precious hours studying for their bar exams to continue her representation after graduation. Their client was a woman seeking asylum from China’s one-child policy, a claim that rarely succeeds. They prepared the woman and her husband for their asylum interview— a nearly full-time job in itself. When she learned her client had been granted asylum, says Ruff, “it was the best moment of my life.”

But traditional skills like effectively preparing and arguing appeals or prepping for hearings no longer suffice in today’s heated immigration climate. Clinics are now teaching creative advocacy— working with resources and constituents outside the legal profession to advance a client’s interests. “Immigration issues are too important to keep doing things the old way,” says Morawetz. “We will work with anyone in any forum. The goal is to give students a real sense of the many tools that can help their clients.” For example, the Civil Legal Services Clinic worked with organizations such as Doctors of the World and Physicians for Human Rights, which conduct medical and psychological evaluations to substantiate the torture and abuse suffered by the clinic’s immigrant clients seeking asylum.

But traditional skills like effectively preparing and arguing appeals or prepping for hearings no longer suffice in today’s heated immigration climate. Clinics are now teaching creative advocacy— working with resources and constituents outside the legal profession to advance a client’s interests. “Immigration issues are too important to keep doing things the old way,” says Morawetz. “We will work with anyone in any forum. The goal is to give students a real sense of the many tools that can help their clients.” For example, the Civil Legal Services Clinic worked with organizations such as Doctors of the World and Physicians for Human Rights, which conduct medical and psychological evaluations to substantiate the torture and abuse suffered by the clinic’s immigrant clients seeking asylum.

Some clients’ cases demand uncommon strategies. In 2002, the Immigration and Naturalization Service imposed a “special registration program” that required males residing in the United States who were citizens of one of 25 predominantly Muslim countries to register in person with the agency. Many who dutifully showed up, however, were arrested and placed in deportation proceedings.

Working with Lutheran Family and Community Services and the New York Immigration Coalition, Immigrant Rights Clinic students Matthew Ginsburg ’05 and Vanessa Lee ’05 represented one such person, Nofrizal Yahya, a then-44-year-old immigrant from Indonesia who had married and had a child during the nine years he had been in the United States. Yahya was a year short of eligibility to claim a “compelling circumstance”—in his case that his U.S. citizen daughter was born with Down syndrome and needed special care—that would likely have made him eligible for permanent residency.

Ginsburg and Lee posted queries with various groups, and found a filmmaker, Jayden Films, willing to make a documentary that would inform the public about special registration and Yahya’s poignant situation. The strategy worked. Removal was selected as a finalist in the Short Documentary category at the 2005 Los Angeles International Short Film Festival. Immigration officials reconsidered the case, and in 2005 entered into a settlement that allows Yahya to live with his family in the United States, though he must report every three months to officials. His daughter is receiving the treatment and schooling he sought.

Omar Jadwat ’01, currently a staff attorney at the ACLU Immigrants’ Rights Project, credits his experience in Morawetz’s Immigrant Rights Clinic with giving him a broader view of his work and the discipline to self-criticize as a means to improve. “You have to sit down and discuss why you’re doing certain things,” he said. “The luxury of clinical work—even though it doesn’t seem like a luxury at the time—is the fact that there’s a reflective process built in.”